Bran Mak Morn: Social Justice Warrior

|

|

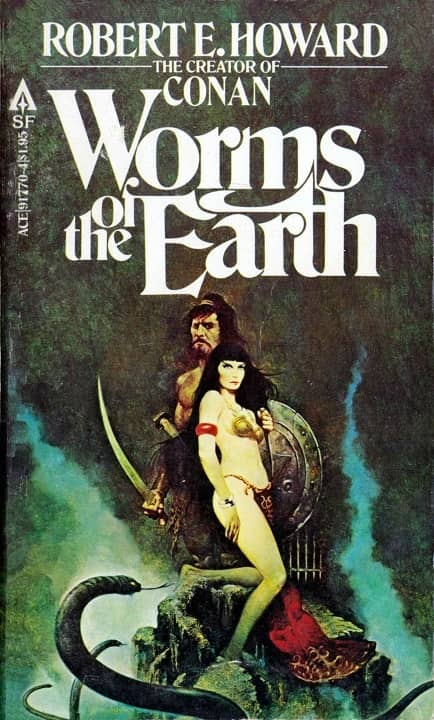

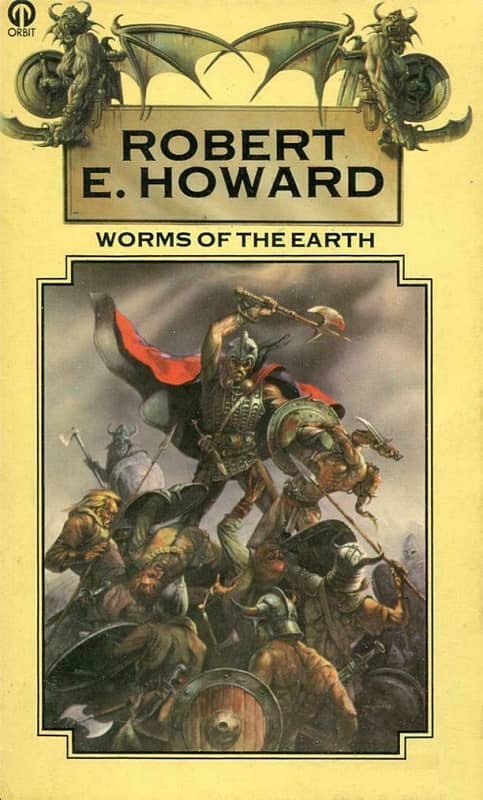

Worms of the Earth by Robert E. Howard (Ace Books, 1979). Cover by Sanjulian

“Worms of the Earth” was published in Weird Tales in November of 1932, and was thus described in the table of contents as “a grim shuddery tale of the days when Roman legions ruled in Britain–a powerful story of a gruesome horror from the bowels of the earth.” It features Bran Mak Morn, the King of the Picts, one of Howard’s barbarian characters. A quasi-Faustian tale, the story dramatizes Bran Mak Morn’s greatest transgression, a dark pact the king makes with diabolic force to avenge his dying and brutalized race: the Picts.

Many consider “Worms of the Earth” one of Howard’s masterpieces, truly haunting and enigmatic, its impact lingering long after a reading, like a stagnant tobacco smell or a leathery flapping of shadowy wings. The story is also notable for its inclusion of allusions to H.P. Lovecraft’s mythos, specifically the ancient Mesopotamian god “Dagon” and the sunken city of “R’lyeh,” home to dreaming Cthulhu. Undoubtedly, the story’s themes of racial degeneracy and the violent power of geologic time are steeped in Howard’s legendary 1930s correspondence with Lovecraft.

[Click the images for weirder versions.]

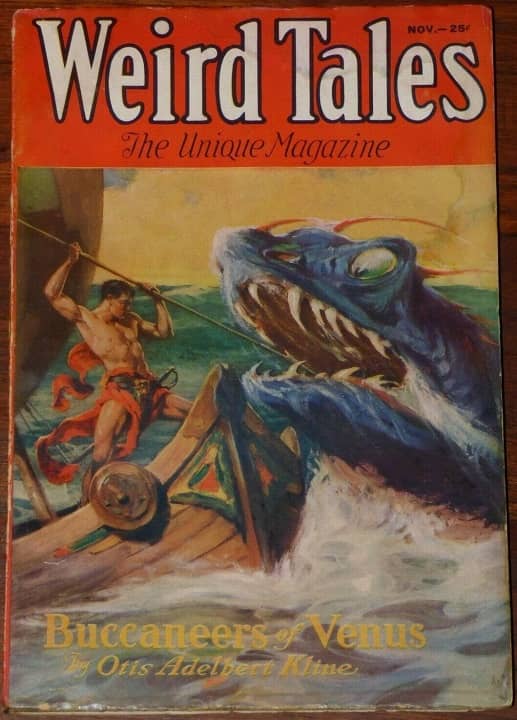

Weird Tales, November 1933, containing “Worms of the Earth”

by Robert E. Howard. Cover by J. Allen St. John

Despite Howard’s pulpster credentials, the young writer demonstrates intellectual ambition in this story. Readers are introduced to a historical framework philosophically anchored in the ideas of “Rome” and “Pictdom,” i.e. “civilization” and “barbarism.” Make no mistake: philosophy aside, this is a fantasy story, a sword and sorcery tale delicately painted with a gossamer-thin layer of history. Howard’s Picts are not the historical Picts, and Howard’s Romans are not the historical Romans. Without question, both tribes are unreal, fictionalized in this story, and fictionalized tendentiously: the Romans are rendered as irredeemable oppressors and the Picts are rendered as the brutally oppressed victims. Artful and strategic distortions allow Howard to bring into focus his troubling theme: the hatred of an oppressed race for their brutal oppressors and the evil consequences of that hatred.

Despite the story’s fantastic nature, it nevertheless engages with the actual, with real oppression, oppressors, and oppressed. Real racism was prevalent in the early 1930s in Howard’s rural Texas, a racially-mixed frontier where the elderly and the descendants of settlers and displaced first tribes remembered (and witnessed) the bloody battle, civil war, banditry, and rapine that characterized what has been mythologized as “the wild west.” Indeed, this earnest engagement with actual racism can be gleaned by contextualizing the “Worms of the Earth” with Howard’s correspondence. In a December 1930 letter to Lovecraft, Howard associates the United States with Rome:

The case of Rome and America are curiously paralleled […]. When the barbarians finally broke into the empire, they found an unwieldy, cumbrous hulk, without identity or union, ready to topple at the first vigorous shove.

In this letter, Howard interprets the destruction of Rome as an accidental boon that reinvigorated Europe. He continues,

Fortunately the tribes who finally trampled the crumblings lines were of a young, vigorous race, capable of rebuilding what they had torn down.

Here is where Howard’s American and Roman analogy becomes nuanced: unlike Rome, which Howard argues was energized by the influx of a “vigorous race,” the United States, he asserts, is doomed in the long run:

“Where in all the world is there an unspoiled, hardy race of clean-blooded barbarians to take the reins of the world when the older peoples decay?”

Put another way, Howard asks who will conquer decadent America and reinvigorate the world? For an answer, Howard casts an unlikely tribe: the Soviet Russians, he speculates, will be the conquering “Aryan tribe” of the United States. But he adds this caveat: “There is too much Mongol blood in the veins of Russia for me to regard that nation as anything but Alien.”

“Race.” “Tribe.” “Clean-blooded.” “Aryan.” These terms indicate that Howard’s historical theory of oppressor and oppressed is bound up with the disturbing, pseudo-scientific racialism prevalent in the interwar period, and which permeates his famous essay of imaginary racial conflict, “The Hyborian Age.” Today, for the most part, such racist pseudo-science has retreated into the lightless grotto of the White Supremacist dark web, a place where intellectually-compromised cowards mutter about “race realism,” power levels, fantasize about their superiority, and cede reason to conspiracy theories.

Unlike today, such eugenic theories were mainstream in the interwar period, disseminated to the public by favorably-reviewed works like The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy by Lothrop Stollard, a book that influenced policies such as the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924. In the same December 1930 letter to Lovecraft, Howard draws upon racialism to saturate his theory of history, of oppressor and oppressed, in a skewed realpolitik based on race. Economics and culture aside, the engine of historical change described in this letter is violent conflict between biological races seeking dominance. These disturbing ideas are further rendered in “Worms of the Earth.”

|

|

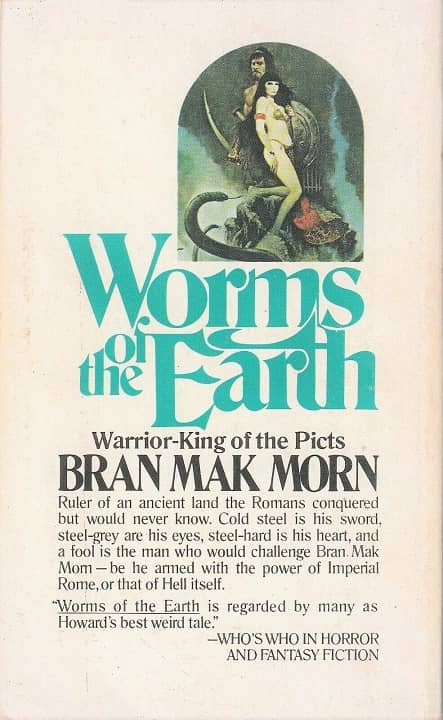

Worms of the Earth by Robert E. Howard (Zebra, 1975). Cover by Jeff Jones

“Worms of the Earth” explores the vengeful plottings of Bran Mak Morn, the king of the Picts. The Picts are a race brutalized and dehumanized by the Romans (i.e., allegorized as Americans). The story begins with the Roman governor, Titus Sulla, stating, “Strike the nails, soldiers, and let our guests see the reality of our good Roman justice.” A Pict is publicly crucified before an audience to demonstrate Rome’s power and superiority. Bran Mak Morn seethes in silence as his fellow Pict is unjustly murdered in grisly spectacle. He fumes quietly in anger, but eventually his rage erupts in this monologue:

Black Gods of R’lyeh, even you would I invoke to the ruin and destruction of those butchers! I swear by the Nameless Ones, men shall die howling for that deed, and Rome shall cry out as a woman in the dark who treads upon an adder!

Bran Mak Morn follows through with his threat, and the sword and sorcery takes off: he makes a dark pact with a witch for the secret location of an artifact of evil, interred in a dark grotto. He plumbs the grotto’s darkness, steals the evil artifact, and then uses the artifact as a hostage to force the alliance of a dehumanized race of pseudo-reptilian monsters who dwell underground. Bran Mak Morn’s plan works: the monstrous race destroys the Romans, captures their leader, Titus Sulla, and delivers the Roman to the eager Bran Mak Morn. Here is where the story takes an enigmatic turn: Titus Sulla’s mind has been blasted by his encounter with the dehumanized race, and in pity — not vengeance — Bran Mak Morn beheads Sulla. By and by, Bran Mak Morn is overwhelmed by a sense of contamination. “There are shapes too foul to use,” he states, before he rides off, with this curse ringing in his ears: “You are stained with the taint […].”

“Worms of the Earth” is an enigma. As Howard is considered more and more by commentators, this tale will be a lightning rod for its enthralling contradictions, its allegorization of interwar pseudo-scientific theories, its overtly racist content, and its relevance to social tensions in the United States today. Scholar Mark Finn makes this insightful observation, explaining the story’s unique potential for interpretation: “Bran offers no comment on his irrational solution.” Thus, critics are compelled to respond. The story ends in “aporia,” in irresolvable tension, and its pregnant undecidedness has enthralled Howard fans over the years.

In commenting on this tale, Patrice Louinet suggests that Bran is a kind of Howardian stand in. In Louinet’s The Robert E. Howard Guide, he writes, “If one had to decide which character was closest to Howard among his many creations, it wouldn’t be Conan or Solomon Kane, but Bran Mak Morn, whose eventual defeat is a certainty, even to himself.” Louinet cites a January 1932 letter to Lovecraft where Howard expresses his affinity for the Picts:

“My interest in these strange Neolithic people was so keen that I was not content with my Nordic appearance, and had I grown into the sort of man, which in childhood I wished to become, I would have been short, stock, with thick, gnarled limbs, beady black eyes, a low retreating forehead, heavy jaw, and straight, coarse black hair.”

Put another way, Louinet’s commentary argues that Howard artistically identified as a racial other, a subaltern “non-Nordic” marked by racial difference. In the American context within which Howard situates his fictional Romans, Howard repudiates his “American/Roman identity” and identifies with the underdogs, the non-Roman “barbarians” brutalized by America/Rome (i.e., indigenous Americans and former African slaves rendered as Picts). If the Picts allegorize indigenous Americans and former African slaves, then is it fair to say that Bran Mak Morn allegorizes what alt-right commentators dismissively refer to as a “Social Justice Warrior,” a person concerned with the systemic oppression of the subaltern?

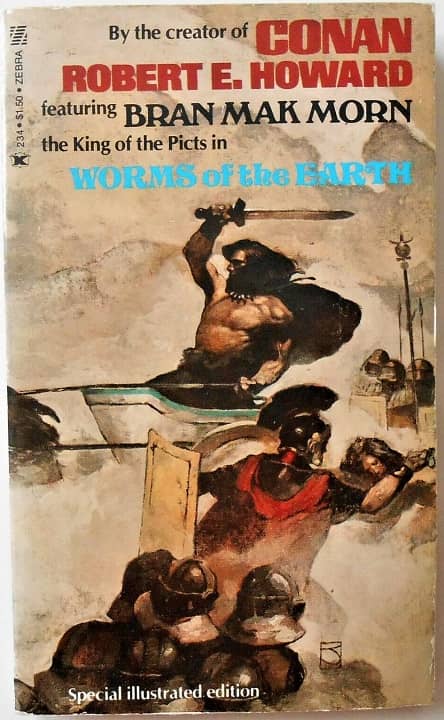

Worms of the Earth (Orbit, 1976), Cover by Chris Achilleos

Mark Finn, in his biography, Blood and Thunder: The Life and Art of Robert E. Howard, views “Worms of the Earth” as the story where Howard was able “to delineate the exact shift in the fate of his Picts,” specifically elucidating the nature of their defeat. One might speculate that for Finn, the crux of “Worms of the Earth” is racial decline and dissolution: viewed from the broad angle of Howard’s oeuvre, this story is notable for how it concludes the story of the Picts in defeat, even as they consummate their vengeance against oppressors.

Even so, some commentators eschew the racial content of “Worms of the Earth” altogether. For example, in their Robert E. Howard: A Closer Look, writers Charles Hoffman and Marc Cerasini interpret the story as an allegory of racially-neutral terrorism:

“From a modern perspective, it illustrates the evils of terrorism. Bran wishes to effect social change and avenge social injustice, but steps beyond all boundaries of acceptable human behavior in these pursuits.”

Other commentators, such as Don Herron, ignore the racial content: in his essay, “The Dark Barbarian,” Herron emphasizes the fantastical elements of this tale, stating,

“In ‘Worms of the Earth’ [Bran Mak Morn] destroys a Roman garrison, but only with the aid of the loathsome worms of the earth — a victory that rings quite hollow in the face the inhuman horrors Mak Morn has loosed upon the world.”

In 2020, in the aftermath of widespread racial protest, populist insurrection, and dehumanizing demagoguery, this story’s relevance endures and is heightened for thoughtful readers. Why? The young Howard knew, perhaps intuitively, that the trauma of American racial conflict is a contaminated wellspring of ever-regenerating violence, hate, and insanity, an unhealed wound that continues to fester and dehumanize all of us. It is surprising that Howard, in his fiction, apparently identifies with the subaltern causes of indigenous tribes, Black Americans, women, and sexual and gender minorities even as he deploys White Supremacist theories of racialism in his correspondence.

Viewed from our contemporary moment, do the Picts lives matter? Do the Romans become the police? And who, and what, are these dehumanized “Worms of the Earth” — these hatesick monstrosities seething in the shadows? If the crucified Pict can be contemporized as George Floyd, a real man, then Bran Mak Morn becomes a warrior for social justice; the worms, the riotous mob assaulting the citadel of democracy.

Jason Ray Carney is a Lecturer in Popular Literature at Christopher Newport University. He is the author of the academic book, Weird Tales of Modernity(McFarland), and the fantasy anthology, Rakefire and Other Stories(Pulp Hero Press). He recently edited Savage Scrolls: Thrilling Tales of Sword and Sorceryfor Pulp Hero Press and is an editor at The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies and Whetstone: Amateur Magazine of Sword and Sorcery.

Nice to see Bran Mak Morn discussed here. I’ve always enjoyed his stories more than Conan for some reason, but I haven’t written a thesis on that :). WOnderful to see Jason Carney here on Black Gate!

Thanks, Seth!

I posted this on Reddit, but might as well re-post it here as well. If you want to interpret Worms of the Earth as a parable on the current political and social situation in the US, given that Bran Mak Morn makes a devil’s contract with the Worms to overthrow a perceived oppressor, wouldn’t he be closer to the Republican Party and its voters that have tainted themselves by embracing Donald Trump and his host of underground extremists in order to overthrow the Democrats, whom they perceive as an existential threat to their concept of the white American way of life?

First, thanks for reading. Second: let me quibble with how you’re using “parable.” Parables are succinct and overtly didactic. I don’t think “Worms” is a parable by that definition. It’s a pulp story. If there is a “message,” it is an obscure and hazy one, and that enigmatic quality is what makes this story so accidentally artful. In the virtual world of this story, whatever side you’re on–Pict, Roman–achieving justice is rendered as a dark (even Faustian) exchange that dehumanizes and contaminates everyone involved. Republican, Democrat, Pict, Roman: specifics aside, excessive tribalism is a dark ritual that threshes demons from the dark. “Worms of the Earth” seemed relevant this week.

I think there’s a connection, albeit not a very straightforward one. I’d see Bran Bran Morn’s relationship with the Romans as broadly analogous to Conan’s relationship with the Numilians in ‘The God in the Bowl’, and by extension, both characters as Libertarian role models. And I guess some white supremicists might identify as Libertarian. I’m speaking as outside observer, though! For what’s it’s worth, I should add that I reckon the common denominator is dislike of ‘big’ government rather than overt racism.

“My interest in these strange Neolithic people was so keen that I was not content with my Nordic appearance, and had I grown into the sort of man, which in childhood I wished to become, I would have been short, stock, with thick, gnarled limbs, beady black eyes, a low retreating forehead, heavy jaw, and straight, coarse black hair.”

??? Any photos I’ve seen of Bob Howard are of a heavy-set, dark-haired man. ‘Nordic’ isn’t the word that springs to mind.

Thanks for reading! Lots to think about. The idea of that Conan is something akin to a “cultural libertarian,” in the sense that he is defined by not being constrained by the conventions of his home culture’s traditions or modes of life. Conan is basically in self-adopted exile from Cimmeria, and so cultural autonomy seems like a key feature of his identity. He is “modern,” and the Cimmerian world he left is gray, homogenous, and “traditional.” Conan is not partisan in any sense. “Red Nails,” for example, is all about anti-partisanship/anti-tribalism, and how in-group/out-group mindsets are the equivalent of psychopathy. Bran Mak Morn is different. Unlike Conan, Bran is a partisan, a tribalist. I’m not sure about that letter regarding his appearance.

Nice to see my favourite fantast artist Chris Achilleos make the cut. Although in this context I think Sanjulian’s artwork is the most relevant, even though I don’t recall Bran Mak Morn traipsing about with a goth lady in the story. Although i have read my fair share of Howard, for whatever reason I have only read the Marvel SSOC adaptation of this specific story, in the Wandering Start colour enhanced version. (Recommended buy if you can find it!)

As to the deeper meaning, I mostly read for escapism so prefer my stories as ripping yarns to entertain, not to think too deeply into. Either way a great take and one I must make a point to read in text. Will leave it there.

Chris Achilleos is so talented. And those Wandering Star editions are wonderful. Reading for escapism is 100% valid and some readers (like myself) take pleasure in adulterating their reading with philosophical musings. No judgments either way here!

[…] SWORD AND ADVOCACY. In “Bran Mak Morn: Social Justice Warrior” at Black Gate, Jason Ray Carney contends Robert E. Howard’s character was an SJW long before the […]

Thanks for reading. I’m not suggesting that and I don’t think such an anti-SJW ethos maps onto the story. The story is more interesting than that, and dynamic. “Worms” is not just a warning against the excesses a particular “tribe,” i.e. “SJWs,” “Trumpist White Nationalists,” “Picts,” “Romans.” The insanity and violence is not just spewing from *one* source. Though a young pulpster, Howard is wiser than that. In the strange world of this story, tribalistic hatred is a timeless, darkly eternal state, from the worms to the Picts to the Romans. It’s profoundly sad. I dare say for Howard we will constantly be caught in a bloody rip tide and so fight eachother as long as their are tribes, i.e. markers of difference. This is an insight that seems native to the soil and time of interear Texas, even as White Supremacy and eugenics drove the world toward hitherto unfathomable ruin.

Interesting article, Jason. I think you may be applying modern theories of deconstructionism into the story more than what Howard intended when he wrote it. I think, based on Howard’s letters to Lovecraft, that “Worms” is little more than Howard writing a cracking good yarn about one of his favorite “peoples” fighting a winning battle against oppressive conquerors and the cost this victory takes on the protagonist, as you wrote, and nothing more. In their letters leading up to the time of Howard writing the tale, Howard and Lovecraft talk about Lovecraft’s admiration for and love of Ancient Rome, and Howard’s love and identification with the “Picts” (as he thought of them, but definitely knew his conception of them was wrong according to the latest anthropology as he states in letters to his friend, Harold Preece in Oct/Nov. 1930, and Lovecraft in January 1932), and the Scots/Gaels. Howard had a complicated approach to Rome: liking it for it’s high level of culture/technology, but ambivalent about its conquering of the Mediterranean. Howard states he was all for Rome conquering the Eastern half of the Mediterranean, but disliked its conquest of Gaul and Britain: “Don’t think I’m fanatic in this matter of Rome. It’s merely a figment of instinct, no more connected with my real every-day life than is my preference for the enemies of Rome. I can appreciate Roman deeds of valor and no one gets more thrill out of Horatius’s stand on the Roman bridge, than I do. I am with the Romans as long as their faces are turned east. While they are conquering Egyptians, Syrians, Jews and Arabs, I am all for them. In their wars with the Parthians and Persians, I am definitely Roman in sympathy. But when they turn west, I am their enemy, and stand or fall with the Gauls, the Teutons and the Picts!” (Lovecraft March 2, 1932). Howard states in a June 1931 letter to Lovecraft: “My sense of placement, as I’ve mentioned, is always with the barbarians outside the walls”, and “Another thing difficult to understand is my aversion toward things Roman. As you say, Rome made no attempt to destroy the folk-traditions of her subjects; life in the Roman republic and early empire must have been far more desirable than life in the later feudal age. Rome built system and order out of chaos and laid down the lines of a solid civilization — and yet the old unreasoning instinct rises in me and I cannot think of Rome as anything but an enemy! Maybe it’s because Rome always won her wars until the very last days, and my instincts have always been on the side of the loser — Celtic instincts again, I suppose”, and later: “My sense of placement, as I’ve mentioned, is always with the barbarians outside the walls”. Howard may have written about wanting to grow up into his conception of a Pict as a young boy, but by the time he wrote “Worms”, he identified and thought of himself more as Gaelic, and having a a big affection/identification with the underdogs/losers as he saw them.

Furthermore, Howard wrote “Worms” as his attempt to write as a Pict, a loser standing outside the walls of an all-powerful encroaching civilization, experiencing the conquest of his homeland and trying to fight against it to no avail. As he writes to Lovecraft in the March 2, 1932 letter about “Worms”: “My interest in the Picts was always mixed with a bit of fantasy — that is, I never felt the realistic placement with them that I did with the Irish and Highland Scotch. Not that it was the less vivid; but when I came to write of them, it was still through alien eyes — thus in my first Bran Mak Morn story — which was rightfully rejected — I told the story through the person of a Gothic mercenary in the Roman army; in a long narrative rhyme which I never completed, and in which I first put Bran on paper, I told it through a Roman centurion on the Wall; in “The Lost Race” the central figure was a Briton; and in “Kings of the Night” it was a Gaelic prince. Only in my last Bran story, “The Worms of the Earth” which Mr. Wright accepted, did I look through Pictish eyes, and speak with a Pictish tongue!”. It looks like Howard was indeed writing with an intellectual ambition as you say, but only in winning against the all-powerful enemy by selling your soul and how that is not worth the cost.

Wow. Insightful, well-informed comment. And thanks for reading. First, I wouldn’t call “Deconstructionist” criticism “modern.” With respect, the Yale School of Deconstructionist Criticism–Paul de Man, J. Hillis Miller, Harold Bloom, etc–was prevalent in the 1970s and part of literary criticism’s history at this point: de Man died in the 80s, Bloom (alas) last year, and J. Hillis Miller is 92. To put it mildly, “Deconstruction is pretty passe now (in academic circles, at least). I never mentioned Derrida here. So, there is no Deconstruction here. Small quibble: but I think you’re using that term in too general of way. People use “Deconstruction” as a blanket term for literary criticism that either they don’t understand or don’t like, and the same goes for the equally loaded term, “postmodernism.” But let me move on to your claims about the story: You write, “‘Worms’ is little more than Howard writing a cracking good yarn about one of his favorite ‘peoples’ fighting a winning battle against oppressive conquerors and the cost this victory takes on the protagonist, as you wrote, and nothing more.” To paraphrase you: “this story is mostly for fun/entertainment and don’t read into too deeply.” As a scholar of popular literature, you can imagine that this is an intellectual lance that I have had to deflect many times (and often against my colleagues in Englsh Departments). So, I vehemently disagree with this sort of closure of meaning and see it as devaluing of artistic popular literature. In my view, it infantilizes of popular/pulp/mass culture. I don’t question *your* intentions, as an individual reader, but I do think such an argument is suspect and often sinister; it is usually only deployed *as a response* to interpretations that people don’t like or that they disagree with. Hyperbolic example for clarity: If one argues that Bran Mak Morn represents a Nordic White Supremacist who fights against encroaching Mediterranean Decadence, a Trumpist Ethnonationalist probably would not critique my argument as “reading too deeply.” They might even cheer it on. BUT! if I compare Bran Mak Morn to those BLM protesters fighting for racial justice, then–and only then–I am conveniently “reading too deeply.” The “it’s just for fun–you’re reading popular literature too deeply” is a red herring that is deployed selectively, imho, to police/control interpretation. Last comment about literary/art criticism in general: works of art do not have inherent, static, objective meanings that readers merely “decode,” i.e. cores of truth that we excavate. Instead, works of art (I’m speaking analogically) are canvases upon which we, as readers, *paint* our interpretations. In other words, reading is “creative,” not just “decoding,” so the conditions of success for a given interpretation is not “right interpretation” or “wrong interpretation.” The condition of success is… is the interpretation “vital” or “flaccid”? To what extent does a generate conversation, engagement, joy, insight, appreciation, and ultimately more art? Saying “Worms” is “just for fun and don’t read it too deeply” does none of that important work.

Sorry I touched a nerve with my remarks. Your paraphrase of my argument is slightly wrong. I specifically stated that the story was for entertainment AND that any deep meaning it had was that winning at all costs can destroy you. Nothing more.

While I understand your thoughts on interpretation of literature, I find it absolutely wrong to impute our modern interpretations on what an author was thinking about and wanted to convey when he wrote his story unless he specifically stated what he was going for in writing the story.

All we can go on is either what he wrote about his work, or told to other people asking about it as to what he was aiming for. Anything else is supposition on our part.

All we have from Howard on “Worms” is he loved his “version” of the Picts, hated Rome’s Western conquests, and viewed himself as linked to underdogs/losers, and wrote it from the standpoint of a Pict. Any interpretations “now” are “our” own interpretations of the story, and should be classified as our “opinion” from what the work made us feel, but may not have been what the author had in mind when he wrote it.

Howard knew he needed to write tales that would entertain readers first and foremost which would have the best chance of selling to earn a living. He would indeed throw in additional meanings to some of his stories that would arise in his debates with Lovecraft such as civilisation vs. barbarism/frontier living, unregulated police being bad among others. All we can state with certitude about “Worms” is that Howard was writing a tale he hoped to sell from the standpoint of someone fighting a losing battle who lost far more of himself to win a meaningless victory, based on the extant statements of Howard himself.

Oh, and having been born in the very early 60’s, “deconstructionism” is still relatively modern to me (wink).

No nerve was touched. Tone is very hard to convey through these comments. You made an interesting, thoughtful comment and it I wanted to repay your thoughtfulness with an equally thoughtful response. To an extent we are agreed about “opinion,” but I would even go so far as to say readers can (and sometimes should) contradict writers’ and their claims about their own work. Even if Howard said this or that, readers have a right to contradict claims. To proscribe interpretation by appealing to intention is called “the intentional fallcy.” W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley wrote the classic essay, “The Intentional Fallacy,” in 1946, that famously articulated this view. That basically argue that works of art–poetry, specifically–are autonomous of artists. For example, J.R.R. Tolkien famously claimed that LOTR had nothing to do with World War II. I think we are right to question that claim.

I would agree with you that readers can contradict and question the claim of what a writer was thinking or wanted to convey in his work based on how it affected the reader. BUT I feel that the reader should definitely state that this is his opinion and may not necessarily be the writer’s. I feel that this distinction is being and has been lost, and that readers/reviewers’ opinions are being accepted uncritically as what the writer was intending.

Thanks for an interesting discussion!

[…] with Bran Mak Morn fighting for his doomed people. Jason Ray Carney in his insightful article, Bran Mak Morn: Social Justice Warrior quotes Howard, who himself was an outcast, on the Picts: “My interest in these strange […]

[…] of non-white characters. In his article Bran Mak Morn: Social Justice Warrior Jason Ray Carney writes about the story Worms of the Earth as a story about oppression, yet recognises that it is also […]

[…] Bran Mak Morn: Social Justice Warrior – Jason Ray Carney […]