Worlds Within Worlds: The First Heroic Fantasy (Part III)

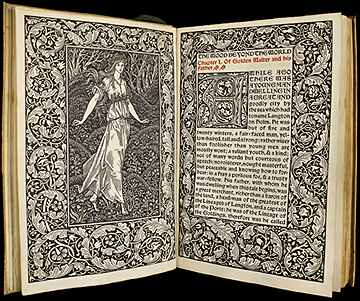

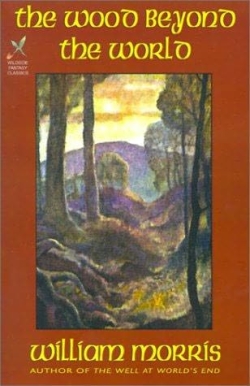

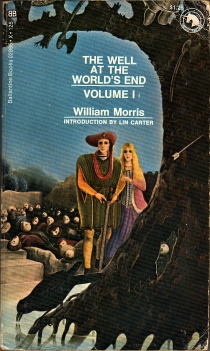

This is the third in a series of posts looking at the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy: that is, the first fantasy to be set entirely in its own fictional world, with no connection to conventional reality at all. It’s an innovation traditionally ascribed to William Morris, but I think I’ve found an earlier writer who deserves that honor.

This is the third in a series of posts looking at the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy: that is, the first fantasy to be set entirely in its own fictional world, with no connection to conventional reality at all. It’s an innovation traditionally ascribed to William Morris, but I think I’ve found an earlier writer who deserves that honor.

In the first post, I considered how to identify a fictional otherworld. I suggested four characteristics, of which a story’s fictional world needed to have at least three to be a true otherworld: its own logic (which might involve, say, the existence of magic), characters who we identified as residents of another world than our own, a coherent history, and a coherent fictional geography. In the second post, I considered ways in which older fantasies were linked to reality — by being set in the past, or in a place beyond contemporary knowledge, or being established as a dream, or as a story within a story, or as a myth. I concluded by discussing what I felt was significant about the idea of otherworld fantasy.

Before going on to present my suggestion for the writer of the first otherworld fantasy, though, I’d like to take a closer look at some past fantasies I thought came very close to presenting self-contained otherworlds. These are works which I don’t think are true otherworld fantasies, but which other people might choose to see as such.

This is the second post in a series trying to answer what looks like a simple question: who wrote the first fantasy set entirely in another world? As I found in my

This is the second post in a series trying to answer what looks like a simple question: who wrote the first fantasy set entirely in another world? As I found in my  Who was the first person to write high fantasy?

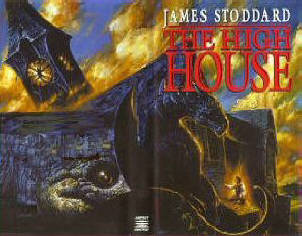

Who was the first person to write high fantasy? In 1998, American writer James Stoddard published his debut novel, The High House, and two years later followed it with a sequel, The False House. They’re two of the more remarkable fantasies I know.

In 1998, American writer James Stoddard published his debut novel, The High House, and two years later followed it with a sequel, The False House. They’re two of the more remarkable fantasies I know.  I don’t know what makes a novel great. Maybe every great book is great in its own way. I suspect, though, that a novel’s greatness resides most often either in its structure (not just its plot, but its balancing of themes and elements, its division into units like chapters, and its decision of what to describe and when) or its prose (its ability to make every word count, not only in depicting character and setting, not only in moving forward story, but in advancing the theme of the book, what it’s about, the idea that prompted the telling of the tale in the first place).

I don’t know what makes a novel great. Maybe every great book is great in its own way. I suspect, though, that a novel’s greatness resides most often either in its structure (not just its plot, but its balancing of themes and elements, its division into units like chapters, and its decision of what to describe and when) or its prose (its ability to make every word count, not only in depicting character and setting, not only in moving forward story, but in advancing the theme of the book, what it’s about, the idea that prompted the telling of the tale in the first place). But Bellairs was more than that. He was also a first-class fantasist, whose one book for adults, The Face in the Frost, is something unique. Written before his tales for children, on its publication in 1969 it was described by Lin Carter as one of the three best fantasies to have appeared since The Lord of the Rings.

But Bellairs was more than that. He was also a first-class fantasist, whose one book for adults, The Face in the Frost, is something unique. Written before his tales for children, on its publication in 1969 it was described by Lin Carter as one of the three best fantasies to have appeared since The Lord of the Rings.

It’s only polite to introduce yourself properly, and as this is my fourth posting on this blog, a proper introduction is really overdue. So: Who am I, and what am I doing here?

It’s only polite to introduce yourself properly, and as this is my fourth posting on this blog, a proper introduction is really overdue. So: Who am I, and what am I doing here? John O’Neill’s editorial in Black Gate 14 touched on gaming, on wargaming and role-playing, and on the way these things shaped the way friends interact. It hit home for me, because I recognised in my life much the same sort of phenomenon John described in his own.

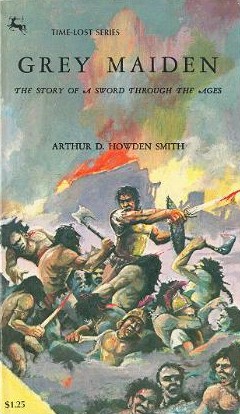

John O’Neill’s editorial in Black Gate 14 touched on gaming, on wargaming and role-playing, and on the way these things shaped the way friends interact. It hit home for me, because I recognised in my life much the same sort of phenomenon John described in his own. I have a habit of buying books — a compulsion, really. Older books, mostly, from book fairs and small used bookstores. Things that look unusual, and which, in the absence of an immediate reason on my part to read them immediately, often sit on my shelves for some time before I get around to them.

I have a habit of buying books — a compulsion, really. Older books, mostly, from book fairs and small used bookstores. Things that look unusual, and which, in the absence of an immediate reason on my part to read them immediately, often sit on my shelves for some time before I get around to them.