Faces in the Mirror

John Bellairs died in 1991, well-known and well-respected as a writer of odd, gothic mysteries for children; the sort of writer who can come up with books called The House With a Clock In Its Walls or The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn, and make them live up to the evocative promise of their titles.

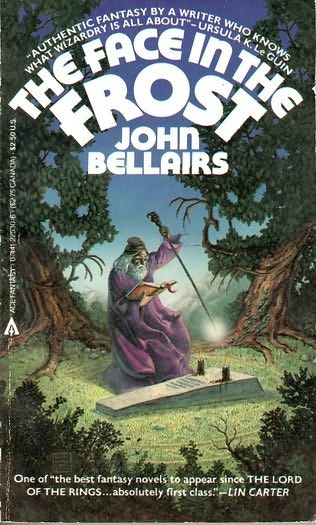

But Bellairs was more than that. He was also a first-class fantasist, whose one book for adults, The Face in the Frost, is something unique. Written before his tales for children, on its publication in 1969 it was described by Lin Carter as one of the three best fantasies to have appeared since The Lord of the Rings.

But Bellairs was more than that. He was also a first-class fantasist, whose one book for adults, The Face in the Frost, is something unique. Written before his tales for children, on its publication in 1969 it was described by Lin Carter as one of the three best fantasies to have appeared since The Lord of the Rings.

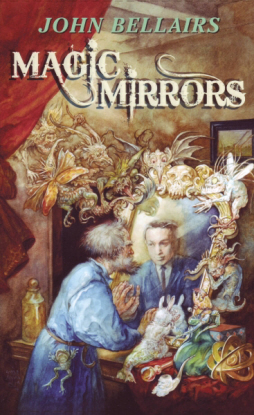

Recently, NESFA Press (NESFA stands for the New England Science Fiction Association) reprinted The Face in the Frost in a volume that also includes the surviving fragment of its uncompleted sequel, The Dolphin Cross, and two of Bellairs’ earlier works, Saint Fidgeta and Other Parodies and The Pedant and the Shuffly. The resulting book, Magic Mirrors, is unconventional but perhaps essential.

The Face in the Frost is no epic quest, nor is it grim dark fantasy, though a superficial description makes it sound like it could be either: It’s a tale of two elderly and slightly bumbling wizards faced with a mysterious darkness that’s threatening everything they know, and the journey they must take to unriddle what it is and how to stop it.

This sounds like an adventure yarn; but it isn’t, really. It’s charming, and often nightmarish. Frequently surreal, it’s weirdly precise. The wizards, for example, are named Prospero and Roger Bacon — but they’re not to be confused with any other characters of the same names. They’re hedge-wizards, living in a medieval land not wholly unlike Ireland, who use magic mirrors to watch Nelson fight at the Nile or the Cubs lose to the Yankees in 1943 — and this may make the book sound like a comedy, but although it is funny, it’s not that, either, not really.

Fundamentally, the book is dreamlike. It lives in its details, in its off-handed erudition, and in its sense of atmosphere — evoked, always, simply and skillfully. There’s nothing complex about it, but it’s consistently precise, its prose clear and sure.

Consider the second paragraph of the book, a description of Prospero’s home:

Inside the house were such things as trouble antique dealers’ dreams: a brass St. Bernard with a clock in its side and a red tongue that went in and out with the ticks as the tail wagged; a five-foot iron statue of a tastefully draped lady playing a violin (the statue was labeled “Inspiration”); mahogany chests covered with leering cherub faces and tiger mouths that bit you if you put your finger in the wrong place; a cherry wood bedstead with a bassoon carved into one of the fat head posts, so that it could be played as you lay in bed and meditated; and much more junk; and deep closets crammed with things that peered out of the darkness off the edges of shelves, frightening the wits out of the wizard as he poked around looking for jars of mandrake root or dwarf hair in aspic. In the long, high living room — heated by a wide-mouthed greenstone fireplace — were the usual paraphernalia of a practicing wizard: alembics, spiraling copper coils, alchohol lamps — all burping, sputtering, and glurping as red, blue, purple, and green liquids boiled, dripped, or just slurched uncertainly in their containers. On a shelf over the experiment table was the inevitable skull, which the wizard put there to remind himn of death, though it usually reminded him that he needed to go to the dentist. One wall of the room was lined with bookshelves, and on them you could find titles such as Six Centuries of English Spells, Nameless Horrors and What to Do About Them, An Answer for Night-Hags and, of course, the dreaded Krankenhammer of Stefan Schimpf, the mad cobbler of Mainz.

The first thing you notice is the sheer linguistic invention. The tone seems to me too restrained to be properly characterised as “exuberant,” but I think there’s still very obviously joy in invention for invention’s sake.

Then perhaps you notice the technical skill of the paragraph, the way the sentences flow easily, though clauses are divided up by an array of commas, colons, semi-colons, parentheses, dashes, and even book titles. The rhythm is varied, but always clear. For all its tricks, it’s easy to read.

Then there’s the shift in tone. The way humour gives way to a touch of horror (“things that peered out of the darkness off the edge of shelves”) before returning to a lighter feel. This, I think, is critical.

The heterogeneity of Prospero’s house is the heterogeneity of the book itself. The range of invention and imagery, the way horror and humour interlock, the odd (“dwarf hair in aspic”) cheek-by-jowl with the concrete and realistic detail (the “wide-mouthed greenstone fireplace”) — this is the style of the book in miniature.

The heterogeneity of Prospero’s house is the heterogeneity of the book itself. The range of invention and imagery, the way horror and humour interlock, the odd (“dwarf hair in aspic”) cheek-by-jowl with the concrete and realistic detail (the “wide-mouthed greenstone fireplace”) — this is the style of the book in miniature.

Oh, yeah: the characterisation of the house is also the characterisation of the wizard who owns it. The way Bellairs describes the features of the place tells us a lot about the man who’s filled it with all those strange and wonderful things.

This isn’t to say Bellairs is perfect as a writer. His plotting skills don’t seem to rise to the potential of the story. The resolution feels quick and anti-climactic. But this in itself seems to sustain the dreamlike feel of the book; just as dreams can call up emotions far more powerful than the dream-images seem to justify, so The Face in the Frost can consistently unsettle you, spook you, in a way that the book itself seems to refuse to explain.

The Dolphin Cross, the unfinished sequel published here for the first time, is just the same. Stylistically, it’s a perfect continuation from The Face in the Frost. There are hints at a stronger plot, but it ends before we find out how Bellairs would have fully developed his tale.

What we do have is almost a story in its own right, though. It’s the first section of what the book would have been, an almost-complete unit (some manuscript pages were missing) that can essentially be read as a novella with a number of loose ends.

Magic Mirrors also reprints Bellairs’ first two published books. Saint Fidgeta and Other Parodies is just as it says, a series of light-hearted, almost rueful parodies of the Catholic Church in America. The Pedant and the Shuffly is a surreal tale of the clash between the two title characters, a mix of Lewis Carroll and Doctor Seuss, something like The Phantom Tollbooth, but crazier.

Both of these works are entertaining, but The Pedant and the Shuffly seems to me to be more interesting insofar as it illustrates something about Bellairs’ work, and that is his tendency to write learned, precise nonsense. You could say it’s an American take on the tradition of English nonsense-writing; it’s certainly a habit of thought that’s on display in The Face in the Frost.

What Bellairs did in that book was not unlike what you’d find in G.K. Chesterton’s fiction: he made a coherent story out of whimsy. Prospero’s a real character, grumpy and absent-minded, and his world brings that out as he wanders around trying to undo whatever it is that threatens them both. But both Prospero and his world are unpredictable, always surprising us with unexpected anachronisms, powers, and depths.

I wonder how much of Prospero was a kind of self-portrait. Text pieces by friends of Bellairs recall him as a shy, somewhat eccentric figure; I wonder whether we can see him in Prospero — not the most powerful of wizards, but in his willfully minor and thoroughly odd way utterly unforgettable.

In the end, Magic Mirrors is worth celebrating for bringing The Dolphin Cross into print. If you’ve read The Face in the Frost you’ll want the book just to read part of the sequel; if you haven’t, this is your chance.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

I love John Bellairs and am so glad to have some of his books. His stories are frightful, dealing with reanimated witches, cursed figurines, but they’re cozy with his descriptions of eating chocolate chips in a family room or frosting a cake. Face in the Frost and The Pedant and Shuffly are wonderful, and is the kind of fantasy I write, and like to read.