The World’s Greatest Paranormal Investigator:Hellboy by Mike Mignola and Sundry Hands

The kinds of stories I wanted to do I had in mind before I created Hellboy. It’s not like I created Hellboy and said, ‘Hey, now what does this guy do?’ I knew the kinds of stories I wanted to do, but just needed a main guy.

Mike Mignola, “The Genesis of Hellboy”. Back Issue! (21)

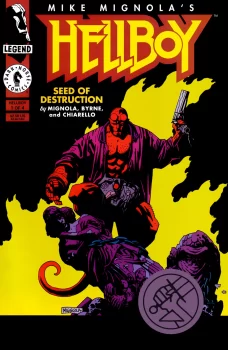

A half-demon paranormal investigator fighting Nazis is how my friend Evan Dorkin described Mike Mignola’s Hellboy to me nearly twenty years ago. He had been reading the books in preparation to write a story for the Hellboy Weird Tales book. He thought I’d really like Mignola’s work, and gave me the first couple of issues. At that point, for all sorts of reasons, I was pretty much through with comics. Hellboy turned out to be like nothing else I’d read. Now, having just finished reading all four new omnibuses, Seed of Destruction, Strange Places, The Wild Hunt, and Hellboy in Hell, along with two additional short story collections (that’s almost 2,400 pages of supernatural awesomeness), I can safely state that this is my favorite comic and, more importantly, a significant and serious work of weird fiction.

In 1991, Mike Mignola sketched a monster to which he added the name Hellboy because he said it made him laugh. A few years later, he used Hellboy as the jumping-off point for a creator-owned comic to be published by Dark Horse. Initially, he toyed with the idea of something like the old Challengers of the Unknown, a team of paranormal investigators created by Jack Kirby (and maybe Joe Simon or maybe Dave Wood). Eventually, he rejected that in favor of focusing just on Hellboy. After a few preview appearances, Hellboy debuted in his own comic mini-series, Seed of Destruction, in 1994.