Invasion! The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells

Across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

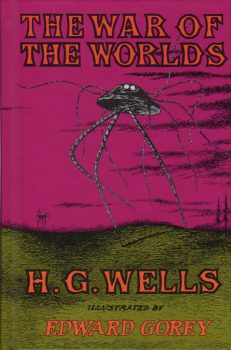

One hundred and twenty-five years after its first publication, H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (serialized 1897, published 1898) remains a brutally effective tale of alien invasion and a critique of imperialism. I can’t remember how young I was when I read it for the first time, but I totally missed the anti-imperialism angle, even though it’s spelled out quite explicitly. Instead, like most readers I’ll bet, what got me were the Martians landing meteor-like in Surrey, the heat ray, and, above all else, the Martian war machines; the great metal tripods. In fact, when I first saw George Pal’s 1953 movie version, I was outraged (and I still am) that he cheaped out and turned Wells’ tripods into legless, floating discs.

Along with Jules Verne, H.G. Wells is responsible for turning science fiction into a popular genre. While Verne seemed more concerned with cool technology, Wells’s literary imagination turned to the big ideas of his age: evolution, class, imperialism, among others. His early run of novels — The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, and The War of the Worlds — are some of the most iconic and influential novels, let alone science fiction novels, of all time. They’ve been filmed numerous times and inspired hundreds of other books. Each one of them is absolutely worth your time (and, hey, they’re all free on Project Gutenberg).

Wells was inspired to write The War of the Worlds when, during a walk through Surrey with his brother, he wondered what it would be like if aliens suddenly appeared out of the sky and began wreaking havoc across England. The idea of England’s green and pleasant lands being invaded (mostly by Germans) had been the focus of the popular genre of “invasion literature” for over twenty years before WotW appeared. He eschewed the Germans in favor of aliens in order to make explicit his critique of colonialism as well as the terror he envisioned in any future war with advanced technology. Wells said he and his brother might have been discussing the fate of the native Tasmanians during their conversation in Surrey. In just twenty-seven years from the arrival of the first British colonists on Tasmania in 1803, all but 47 of the 7,000 native Tasmanians died — and those 47 were in concentration camps. Later historians have attributed the deaths largely to disease, but nearly one thousand Tasmanians were killed during the Black War (sometime in the 1820s-1832). 1897 was the height of British imperialism and the perfect time for a literary attack.

WotW starts slowly, as the unnamed narrator describes watching explosions on the Martian surface from an observatory. Months later a large cylinder crashes into the Surrey countryside at Woking. Eventually, the cylinder opens and several Martians emerge:

WotW starts slowly, as the unnamed narrator describes watching explosions on the Martian surface from an observatory. Months later a large cylinder crashes into the Surrey countryside at Woking. Eventually, the cylinder opens and several Martians emerge:

A big greyish rounded bulk, the size, perhaps, of a bear, was rising slowly and painfully out of the cylinder. As it bulged up and caught the light, it glistened like wet leather.

Two large dark-coloured eyes were regarding me steadfastly. The mass that framed them, the head of the thing, was rounded, and had, one might say, a face. There was a mouth under the eyes, the lipless brim of which quivered and panted, and dropped saliva. The whole creature heaved and pulsated convulsively. A lank tentacular appendage gripped the edge of the cylinder, another swayed in the air.

Those who have never seen a living Martian can scarcely imagine the strange horror of its appearance. The peculiar V-shaped mouth with its pointed upper lip, the absence of brow ridges, the absence of a chin beneath the wedgelike lower lip, the incessant quivering of this mouth, the Gorgon groups of tentacles, the tumultuous breathing of the lungs in a strange atmosphere, the evident heaviness and painfulness of movement due to the greater gravitational energy of the earth — above all, the extraordinary intensity of the immense eyes — were at once vital, intense, inhuman, crippled and monstrous. There was something fungoid in the oily brown skin, something in the clumsy deliberation of the tedious movements unspeakably nasty. Even at this first encounter, this first glimpse, I was overcome with disgust and dread.

Earth’s gravity proves too strong for their Mars-evolved physiognomies and they retreat to the cylinder. When an embassy of locals carrying a white flag approaches the cylinder, they and much of the surrounding countryside are incinerated by an invisible heat ray. Still, the arrival of a large military contingent reassures the populace. Unfortunately for Britain, the Martians have made provisions for gravity and Victorian weaponry.

And this Thing I saw! How can I describe it? A monstrous tripod, higher than many houses, striding over the young pine trees, and smashing them aside in its career; a walking engine of glittering metal, striding now across the heather; articulate ropes of steel dangling from it, and the clattering tumult of its passage mingling with the riot of the thunder. A flash, and it came out vividly, heeling over one way with two feet in the air, to vanish and reappear almost instantly as it seemed, with the next flash, a hundred yards nearer. Can you imagine a milking stool tilted and bowled violently along the ground? That was the impression those instant flashes gave. But instead of a milking stool imagine it a great body of machinery on a tripod stand….

….Seen nearer, the Thing was incredibly strange, for it was no mere insensate machine driving on its way. Machine it was, with a ringing metallic pace, and long, flexible, glittering tentacles (one of which gripped a young pine tree) swinging and rattling about its strange body. It picked its road as it went striding along, and the brazen hood that surmounted it moved to and fro with the inevitable suggestion of a head looking about. Behind the main body was a huge mass of white metal like a gigantic fisherman’s basket, and puffs of green smoke squirted out from the joints of the limbs as the monster swept by me. And in an instant it was gone.

From the first appearance of the tripods, it becomes clear that humanity might be facing a losing battle. Each time the tripods are thwarted they reveal new responses. When artillery destroys some of the war machines, the Martians unleash their most terrible weapon, a thick, poison smoke that kills everything in its path. Even before they have a chance to fire, the last great military force defending London is wiped out in mere moments.

Partway through the book, the narrator’s brother, also unnamed, is introduced. A medical student in London, he witnesses the Martian assault on the city, its fall, and the uncontrolled exodus of its survivors. The Martians not only kill but also capture many people, tossing them into great metal baskets. He and other refugees attempting to flee to the continent in a small fleet experience a moment of hope when the torpedo ram, HMS Thunder Child, destroys two tripods. Only the ship’s self-sacrifice, though, allows the convoy to make good its escape.

With the fall of London, southern England, at least, is under the metal tentacle of the Martians. The second part of the book returns to the original narrator and describes his experiences during the Martian dominance. This part of WotW takes on tones almost like a post-apocalyptic novel. Society is shattered, the vast majority of the population has died or fled, leaving behind only stragglers fighting to survive. A red Martian plant has spread kudzu-like across the green fields of England, even clogging the rivers and climbing up bridges and buildings. When a Martian cylinder crashes near a building he’s hiding in, he discovers the fate of the prisoners in the basket — exsanguination to feed the Martians.

Wells explores the effect of the sudden and overwhelming victory of the invaders. He clearly had little hope his fellow Englishmen wouldn’t fail in the face of such terrible events. A clergyman loses what little faith he might have ever possessed and goes dangerously insane. A soldier loses himself in plotting ridiculous schemes for guerilla war. Even the narrator is driven toward madness when he enters the skeleton-littered, shattered remains of London.

Of course, the great bit of fate that saves humanity is revealed on the narrator’s arrival in London. Unprepared for the environment, the Martians succumb to Earthly disease. Despite all the destruction they’ve caused, Wells manages to evoke a moment of, if not sympathy, empathy for a dying Martian in one of the book’s most haunting moments.

I came into Oxford Street by the Marble Arch, and here again were black powder and several bodies, and an evil, ominous smell from the gratings of the cellars of some of the houses. I grew very thirsty after the heat of my long walk. With infinite trouble I managed to break into a public-house and get food and drink. I was weary after eating, and went into the parlour behind the bar, and slept on a black horsehair sofa I found there.

I awoke to find that dismal howling still in my ears, “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla.” It was now dusk, and after I had routed out some biscuits and a cheese in the bar — there was a meat safe, but it contained nothing but maggots — I wandered on through the silent residential squares to Baker Street — Portman Square is the only one I can name — and so came out at last upon Regent’s Park. And as I emerged from the top of Baker Street, I saw far away over the trees in the clearness of the sunset the hood of the Martian giant from which this howling proceeded. I was not terrified. I came upon him as if it were a matter of course. I watched him for some time, but he did not move. He appeared to be standing and yelling, for no reason that I could discover.

I tried to formulate a plan of action. That perpetual sound of “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” confused my mind. Perhaps I was too tired to be very fearful. Certainly I was more curious to know the reason of this monotonous crying than afraid. I turned back away from the park and struck into Park Road, intending to skirt the park, went along under the shelter of the terraces, and got a view of this stationary, howling Martian from the direction of St. John’s Wood. A couple of hundred yards out of Baker Street I heard a yelping chorus, and saw, first a dog with a piece of putrescent red meat in his jaws coming headlong towards me, and then a pack of starving mongrels in pursuit of him. He made a wide curve to avoid me, as though he feared I might prove a fresh competitor. As the yelping died away down the silent road, the wailing sound of “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” reasserted itself.

I came upon the wrecked handling-machine halfway to St. John’s Wood station. At first I thought a house had fallen across the road. It was only as I clambered among the ruins that I saw, with a start, this mechanical Samson lying, with its tentacles bent and smashed and twisted, among the ruins it had made. The forepart was shattered. It seemed as if it had driven blindly straight at the house, and had been overwhelmed in its overthrow. It seemed to me then that this might have happened by a handling-machine escaping from the guidance of its Martian. I could not clamber among the ruins to see it, and the twilight was now so far advanced that the blood with which its seat was smeared, and the gnawed gristle of the Martian that the dogs had left, were invisible to me…

…As I crossed the bridge, the sound of “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” ceased. It was, as it were, cut off. The silence came like a thunderclap.

I first reread The War of the Worlds a decade or so back and I was amazed at the cold ruthlessness of the Martians in their efforts to conquer England. I found it even more striking this time around. The Martians, like most Earthly colonialists, have no qualms about using overwhelming force to achieve their aims. In the battle of Omdurman, fought the year WotW was published, 25,000 British and allied troops killed a third of the 52,000 attacking Sudanese troops at a loss of only about 50. The book’s violence is an explicit rejoinder that still resonates more than a century later. Look at the wars taking place in Tigray and Ukraine if you think such pitilessness is a thing of our collective past.

Having just written about A Princess of Mars, I wasn’t surprised to learn that Wells was influenced by the same contemporary theories about Mars as Burroughs was. Mars was thought to be a cold and dying world and any inhabitants would have to struggle to survive decreasing supplies of necessities. This concept led Burroughs to imagine and create tales of adventure. For Wells, it established the reason for the Martians’ invasion of Earth. Not only is WotW a forerunner of all alien invasions stories to come, it’s also a forerunner of hard science fiction. Building on the science of his day, Wells carefully plotted out and reasoned the whys, wherefores, and hows the Martian invasion would come about. That lack of the fantastic is a strong part of why WotW holds up so well to this day.

I went on a big Wells kick about twenty years ago after reading Stephen Baxter’s The Time Ships, a sequel to The Time Machine as well as numerous other Wells stories. After revisiting The War of the Worlds, I feel such a kick coming on again. If you have somehow missed this short, gripping book, I strongly recommend you fix that at once.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. There’s a monthly piece by him at Tales from the Magician’s Skull you should be reading, too. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

My parents bought me an omnibus volume of Wells’ work one Christmas, which , besides a handful of short stories, included “The Time Machine” and “The War of the Worlds.” I read both novels as a college freshman (1969), then didn’t read either one again until 2004, when I was given a chance to create, and teach, a science fiction course for the college that employed me, a course I taught 3 more times before my retirement. I always began the course with the two novels, and because of our limited technology at my college, I was unable to show clips from the films of either one until 2011. Rod Taylor’s 1960 film, despite its many flaws, remains the better version of “The Time Machine,” and although many prefer 1953’s “War” with Gene Barry, I chose to show the Tom Cruise remake to my 2015 class — the first half hour, anyway, which remains eminently watchable. But it took my 4th reading of the novel, for that 2015 class, of the description of the aftermath of the first few Martian landings, before I truly appreciated what Wells accomplished. By 2015, I’d seen so much film and TV and cable coverage of the devastation wrought in the first two world wars, plus the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, as well as the carnage in Viet Nam, the Gulf War, Serbia, Afghanistan, and Syria, that it was easier to picture mentally the horror visited on Earth by the Martians. How fitting, unfortunately, that we’re getting a repeat of the brutalities of war, in Ukraine, as this piece is posted.

The War of the Worlds was the second Wells novel that I read, after getting a Scholastic Book Services collection, The Time Machine and Other Stories. I seem to remember the anti-imperialism message, as Wells directly made the comparison between dugout-canoe-paddling indigenes and the outmatched English. And I, too, was disappointed by the “floating” tripods that George Pal used in his 1953 adaptation. But he did frighten my younger self, especially when the cross-bearing clergyman got fried.

Coincidentally, I was earlier this evening enjoying a pint of “Fake Radio War”, a West Coast-style IPA made by Forgotten Boardwalk (Cherry Hill, NJ), named in honor of the other Welles who rose to fame from a tale of a Martian invasion. Slightly heavy (7.4% ABV), nicely hoppy (Cascade, Centennial, Amarillo).

The opening of THE WAR OF THE WORLDS is one of my favorites of any book: “No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own…” and etc. Gives me a shiver every time. Aliens watching humanity in the NINETEENTH CENTURY. Brrr.

When I grew older, I also realized how extraordinarily moving the last sentence is. I won’t quote it here, out of respect, but suffice it to say the story ends on a personal note, not a grandiose one, and it’s one of Wells’ most powerful, and probably overlooked, moments.

The great Richard Burton narrates that opening in a musical version of “War/Worlds” done by Jeff Wayne — and with his very precise British accent, it’s chilling!

I forgot to mention that album, sheesh

Oh, absolutely! It’s a remarkably emotionally affecting book

Wells was unthinkably forward for his times, radical left before it was ‘fashionable’ (several times, depending on definition of the politics) and he was disgusted by the almost open slaughter of the Tasmanians so he wrote it in a rage. Save the also controversial “Unparalleled Invasion” by Jack London there was no fiction that showed a real threat to the British Empire at the time. So an alien invasion proved a good analog and the concept proved much greater than the spark that inspired it. One man’s Opinion anyways.

I think they used to have pride in having a stuffed “Native” they shot on a trip – to the point where curiosity shops would SELL human taxidermy. Tasmanians were the rage because well they were getting RID of them quite openly and turning their effete noses at the Americans for failing to manage a final solution to the Native American problem despite the constant lobbying of writers such as Engles and especially Baum. I’m sure like the Egyptian Mummy kept on hand for a party to impress noble guests – an “Unwrapping Party” the “Stuffed Hottentot” now is in a cellar somewhere as a dark legacy they don’t talk about…

Personally I’m a bit miffed on the re-re-remake whatever of “Dune”. All the promotional buzz no one seems to be talking about Herbert’s tributes to HG Wells. The most blatant of course is the “Ornihopter” which inspired the RL Helicopter and I think they only didn’t name it that for fear of some coffin feeder of Wells demanding money. IMO all Wells would have done is ask politely and extort if needed a few rides in the thing as his protagonist did in one of his novels… This is from “The sleeper Wakes” one of his early novels that most overlook due to fears of promoting ‘socialist’ leanings he had that were blatant there. I read it – frankly some of the ‘rebel leaders’ reminded me of Lenin and Stalin but it was written way before. However he predicted “Streaming media on the Internet” in that book. Also – well I haven’t watched the modern “Dune” but do they include that phrase of “The sleeper must awaken”?