Some Tales from Night’s Plutonian Shore: My Favorite Edgar Allan Poe Stories

I do not have a precise memory of when I first read one of Edgar Allan Poe’s tales. Perhaps it was a bowdlerized version of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” perhaps “Some Words With a Mummy” in one of my grandmother’s Reader’s Digest omnibuses. It might have been the Classic Comics version of “The Pit and the Pendulum.” I definitely saw most of the Roger Corman movie adaptations with Vincent Price on the 4:30 Movie on ABC. I know I picked up a copy of Scholastic Book’s collection, Eight Tales of Terror, at a used book sale at Our Lady of Good Counsel. The important thing is, Edgar Allan Poe‘s creations have been with me as a reader of the weird and the fantastic from my earliest days.

I do not have a precise memory of when I first read one of Edgar Allan Poe’s tales. Perhaps it was a bowdlerized version of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” perhaps “Some Words With a Mummy” in one of my grandmother’s Reader’s Digest omnibuses. It might have been the Classic Comics version of “The Pit and the Pendulum.” I definitely saw most of the Roger Corman movie adaptations with Vincent Price on the 4:30 Movie on ABC. I know I picked up a copy of Scholastic Book’s collection, Eight Tales of Terror, at a used book sale at Our Lady of Good Counsel. The important thing is, Edgar Allan Poe‘s creations have been with me as a reader of the weird and the fantastic from my earliest days.

It’s been a very long time since I’ve actually read any of Poe’s stories, so, as the Halloween season is upon us, it seems the proper time to return to them. I had no doubt I would still enjoy them, but I really had no idea just how good and groundbreaking they really are. Lovecraft, in his seminal essay, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” stated that by focusing on the psychological and not the Gothic, “Poe’s spectres thus acquired a convincing malignity possessed by none of their predecessors, and established a new standard of realism in the annals of literary horror.” I don’t think it’s an overstatement. There are few boogeymen or vampires here; instead, it’s mostly warped and broken minds, the sadism of the vengeful, and the nightmares of the delirious.

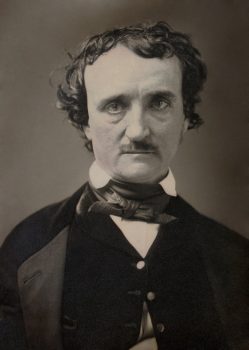

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) is credited with creating the detective story (he didn’t), the modern short story (he was one of the earliest American practitioners of the form), and contemporary horror fiction (he helped). His life was plagued by misfortune and missteps and to this day, his death at the unfortunate young age of forty remains a mystery, though it has been attributed to alcoholism, drug addiction, syphilis, and even murder. Whatever the circumstances of his life, his work remains one of the pinnacles of American writing, of Romanticism, and of weird fiction.

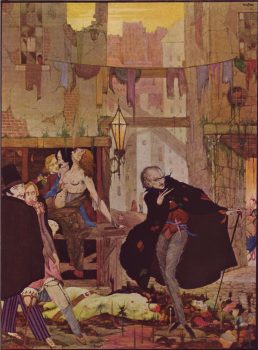

I began my sojourn among the dread shadows of Poe’s imagination with my favorite, “The Man of the Crowd,” (1840). The unnamed narrator describes a night following a strange man who moves silently through the streets of London like a shark, never stopping, never sleeping. Always, he seeks a crowd to swim through, panicking when he finds himself alone, regaining his nervous composure only when he finds another mass of people.

Not a tale of blood and murder, it is, nonetheless, an unsettling one. When I first read this story some thirty years ago, I was completely taken aback by the modern feel of the story. A nameless figure moving endlessly through the streets of a great urban pile seemed far more appropriate to our anonymous modern age than the early Victorian age. Part of Poe’s genius is his ability to correct that notion and point out just where the world is headed — a place of teeming, faceless masses, impenetrable to observation.

Not a tale of blood and murder, it is, nonetheless, an unsettling one. When I first read this story some thirty years ago, I was completely taken aback by the modern feel of the story. A nameless figure moving endlessly through the streets of a great urban pile seemed far more appropriate to our anonymous modern age than the early Victorian age. Part of Poe’s genius is his ability to correct that notion and point out just where the world is headed — a place of teeming, faceless masses, impenetrable to observation.

At the beginning of the story, the narrator tells the reader:

“It was well said of a certain German book that “er last sich nicht lesen” — it does not permit itself to be read. There are some secrets which do not permit themselves to be told.”

At the end, he states:

“‘The old man,’ I said at length, ‘is the type and genius of deep crime. He refuses to be alone. He is the man of the crowd. It will be vain to follow, for I shall learn no more of him, nor of his deeds. The worst heart of the world is a grosser book than the ‘Hortulus Animae,’ and perhaps it is but one of the great mercies of God that ‘er last sich nicht lesen.'”

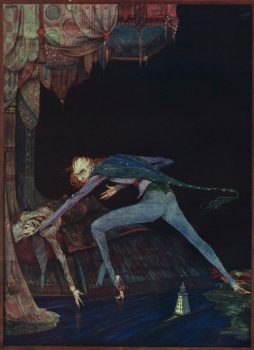

“The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839) is the strangest of the stories I chose. Is the inbred and diseased House of Usher, the family, reflected in and causing the decay of the House of Usher, the house, or is it the other way around? It is a question that runs through the story.

Again, the story is told by an unnamed narrator. He has been summoned by his friend, Roderick Usher, as he has developed a mental disorder and requires help. Upon arrival at the crumbling House of Usher, he notices that the building itself, perhaps reflecting the decayed nature of his friend’s family, is slowly sinking into the swamps, rotting away, covered in fungus. He also notices a thin crack running from the roof down to the foundation below the earth.

Again, the story is told by an unnamed narrator. He has been summoned by his friend, Roderick Usher, as he has developed a mental disorder and requires help. Upon arrival at the crumbling House of Usher, he notices that the building itself, perhaps reflecting the decayed nature of his friend’s family, is slowly sinking into the swamps, rotting away, covered in fungus. He also notices a thin crack running from the roof down to the foundation below the earth.

The narrator soon learns that Madeline Usher, Roderick’s sister and only living relative, has fallen victim to an even greater malady.

The disease of the lady Madeline had long baffled the skill of her physicians. A settled apathy, a gradual wasting away of the person, and frequent although transient affections of a partially cataleptical character, were the usual diagnosis.

When she seemingly dies and Roderick insists on entombing her in the family crypt prior to a final burial (for fear her corpse might be disinterred and stolen by medical men), one knows something unpleasant is coming. And it does.

“The Pit and the Pendulum” (1842) is utter historical nonsense and utterly unnerving. Condemned by the Spanish Inquisition, our narrator is cast into a dungeon with a deep pit. From the opening lines, the focus is on the terror he experiences in the face of the unknown tortures to which he is about to be subject. Even more discomfiting are the moments when he believes he is safe only to discover his plight has become worse.

Eventually, he faces the terrors of the titular device, a great scythe-like blade suspended above him swinging inexorably downward toward his bound body. The whole story is an exquisite, unpleasant progression of a man “sick unto death” from the fear of a death most terrible.

Another story that feels modern, in that it’s told from a psychotic’s point of view, is “The Tell-Tale Heart,” (1843). Despite all evidence to the contrary, the narrator informs us he is completely sane.

Another story that feels modern, in that it’s told from a psychotic’s point of view, is “The Tell-Tale Heart,” (1843). Despite all evidence to the contrary, the narrator informs us he is completely sane.

True! — nervous–very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses — not destroyed — not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily — how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

More than any of the other stories, this one digs into the psychologically disturbed mind of its character. Slowly, Poe provides the reader with the details and reasons — bonkers as they might be — that lead the narrator to the commission of a heinous crime.

Poe is at his most sadistic in “The Cask of Amontillado,” (1846). For the first time, we learn the name of a story’s narrator: Montresor. Driven to seek revenge for a “thousand injuries,” Montresor has determined to wreak a terrible punishment on an Italian nobleman, Fortunato. We never learn precisely what his poor victim did to earn his fate. All we really come to know is that whenever Montresor sees Fortunato, he smiles at him while contemplating his “immolation”.

One night during Carnival, Montresor lures the wine-loving Fortunato to his doom with the temptation of a new barrel of Amontillado. His fate comes upon him completely unexpectedly. When Fortunato realizes his situation is not a joke, despite being dressed as a fool, he utters one of the most pitiable lines in literature. In return, his tormentor utters one of the coldest.

“Ha! ha! ha! — he! he! he! — a very good joke, indeed — an excellent jest. We will have many a rich laugh about it at the palazzo — he! he! he! — over our wine — he! he! he!”

“The Amontillado!” I said.

“He! he! he! — he! he! he! — yes, the Amontillado. But is it not getting late? Will not they be awaiting us at the palazzo, the Lady Fortunato and the rest? Let us be gone.”

“Yes,” I said, “let us be gone.”

“For the love of God, Montresor!”

“Yes,” I said, “for the love of God!”

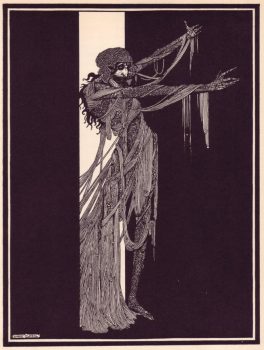

Finally, in “The Masque of the Red Death,” (1842), Prince Prospero prepares an elaborate retreat to hide away from the plague, the Red Death, ravaging his land. Inside its elaborately painted walls, he has invited a thousand “hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court.” While half the population of his dominions has perished, the prince and his companions enjoy wild revels. When a stranger costumed as Red Death itself makes a sudden appearance, things take a turn for the grim. It’s the one story here that has an explicitly supernatural element (one can make a possible case for “Usher”) and the result is a hothouse nightmare of a story that leaves frightening colors and images stamped on a reader’s brain.

Finally, in “The Masque of the Red Death,” (1842), Prince Prospero prepares an elaborate retreat to hide away from the plague, the Red Death, ravaging his land. Inside its elaborately painted walls, he has invited a thousand “hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court.” While half the population of his dominions has perished, the prince and his companions enjoy wild revels. When a stranger costumed as Red Death itself makes a sudden appearance, things take a turn for the grim. It’s the one story here that has an explicitly supernatural element (one can make a possible case for “Usher”) and the result is a hothouse nightmare of a story that leaves frightening colors and images stamped on a reader’s brain.

There is no avoiding, not that one should want to, the power and impact of Edgar Allan Poe on American and supernatural fiction. His stories and poems (the poems I leave to more skilled hands to discuss) have influenced generations of writers. They’ve continued to be read and adapted from his death through today. If, by some strange, odd, un-American circumstance, you have not already treated yourself to Poe’s stories, today’s the day to cry “Nevermore!”

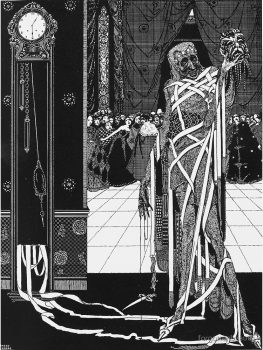

Note: the illustrations are by Harry Clarke, an important member of the Irish Arts and Crafts movement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-So0VCW3uA

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Like you, I read all Poe’s short stories many moons ago (we had an omnibus edition at home). Some I’d already come across in graphic form – e.g. I think I read at least three versions of A Cask of Amontillado in various comics. The Berenice in Creepy made a far bigger impression on me than the story itself. Rich Corben’s The Oval Portrait less so – it came across as kind of ridiculous, although I usually liked his work.

As you probably know, the illustrations in your article are all by an Irishman – Harry Clarke – who was mainly a stained-glass designer, and a prolific one at that (they say you’re never more than a few miles from a sample of his work, regardless of where you are in Ireland).

I remember The Oval Portrait! No memory if it was good or not, but I was/am a Corben fan.

Poe is one of the greats!

Indeed!