Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: Of Lambs and Lizardmen

|

|

|

The Ring-Sworn Trilogy by Howard Andrew Jones: For the Killing of Kings (Feb 2019), Upon the Flight of the Queen

(November 2019) and the forthcoming When the Goddess Wakes (April 2021)

A bit of prologue and some full disclosure to the Gentle Reader

The purpose of this column has been looking at the challenges of historicity vs. fantasy in the process of world-building; well at least when the fantasy in question is trying to be either realistic or set in our world or a near-neighbor. From contrasting the visual departure of Jackson’s LotR films as a more effective means of showing the vast sweep of Middle Earth’s history, to critiquing the swordplay of the Witcher TV show, to interviewing authors who play in both the worlds of Historical Fiction and Fantasy, I’ve come to realize we have a pretty clear continuum:

- Historical Fiction – just what it says. Whether it’s set in the Paleolithic or WWII, it’s a story set in our own past, with the ostensible goal of painting a portrait of that time and place.

- Historical Fiction with Elements of “Magical Realism” – really more of a technique of “literature” but the story is more or less as above but there may be hints or some unexplained and unexplainable element.

- Historical Fantasy – this is a specialty for folks like last month’s interviewee Scott Oden. Our historical past, only elements of magic, monsters, etc., exist, something like a “secret history.” A lot of traditional sword & sorcery exists here, but so does the fantastical work of writers like Judith Tarr or G. Willow Wilson.

- Low Fantasy in a Secondary World – the world I NOT ours, and may not even be based on any clear cognate of our civilizations, but it’s “realistic” in the sense that it’s technology and structure follows our historical models. Magic and monsters exist, but farming gets done with an iron plow and three-field rotation, people ride horses and camels (or something like them), etc. A lot, if not most, of fantasy fits this model and fantasy.

- High Fantasy – Magic is powerful and sweeping, there are non-human races who can do magical things, the gods may be capable of manifesting themselves or their will, etc. A lot of epic fantasy fits into this mode.

We can quibble on where those lines are (Tolkien is High Fantasy, but is Martin?), and maybe there are further subdivisions (for example, Urban Fantasy overlays the last two), but the definitions work for this column because the further you go from #1 on the continuum, the less important “historicity” becomes.

Which brings me to my guest….

GDM: Howard, it occurred to me that you are one of the few folks I can think of who has worked in all these categories! As an editor, you brought the entire canon of the early 20th-c historical adventure writer, and historian, Harold Lamb into print (in a really handsome set of books, I’ll add); as a writer, you’re novels and stories featuring the Arabian historical fantasy swashbuckler/occult investigator duo Dabir & Asim is decidedly Historical Fantasy, your short stories of the Hannibal-like character Hanuvar are Low Fantasy, and your current novel series, The Ring-Sworn Trilogy, is very much High Fantasy. Of these sub-genres is there one that you love best?

HAJ: To my mind, I’m always writing some variation of sword-and-sorcery, and I’d say when it’s at its best, I most love that genre. Dabir and Asim may be investigating the occult in the wonderful, frightening Arabian Nights that never were, but they’re also fighting monsters and wizards, usually with swords. Hanuvar is straight-up sword-and-sorcery, but he isn’t the usual wandering hero; he’s a lone, determined man on an impossible quest to save his remaining people. And I think that while The Ring-Sworn Trilogy is marketed as high or epic fantasy it’s actually modern sword-and-sorcery. It doesn’t have any stable boys destined for greatness, magic is hardly an easy ubiquitous thing, and I don’t THINK it’s overstuffed with talkety talkers stopping the momentum to talk about background. Oh, and it has a boatload of important swashbuckling female characters, starting with the central protagonist.

OK, we could do an entire interview on just this, and we’ll get to Ring-Sworn more soon… but I mentioned Zelazny and Amber… and Kyrkenall might as well be the 10th Prince in Amber, and N’lahr is a close-cousin to Benedict of Amber.

That, sir, is high praise. Benedict remains among my very favorite characters in all fantasy literature.

Really, I tell people Amber is what happens if you hire Raymond Chandler to write an epic fantasy: clipped, quick dialogue that is punctuated by action, sweeping vistas but you only look at them breathily as you zoom by, and heroes that are both heroic and flawed.

Oh, absolutely. I came to Chandler only within the last eight years or so and found him a revelation. I fell in love with his prose, and with much of the hard-boiled school, with its battered knights in trench coats struggling to achieve justice in a weary world. And I also couldn’t help noticing that Zelazny straight up stole the middle section of Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely to open the first Amber novel!

Well, Corwin isn’t quite Philip Marlowe with a sword, but… Anyway, can you imagine how big the Amber books would be if, say, Brandon Sanderson or Steve Erickson wrote them? I guess, in a sense, that’s the difference.

There’s a kind of fantasy literature descended from Jordan where each book is rather like an entire season of a television show, and a large number of readers have come to think of that as the default style of presenting a fantasy story. While I have read and liked some of those books, I usually prefer shorter novels where character and backstory are revealed through action (rather than extended backstory) and momentum rarely flags. Oh, and wild world building is mighty pleasing. Amber certainly delivers that.

I want to start with the project you are probably least-known for, which is editing the works of Harold Lamb. Lamb was a major influence on a number of early 20th century writers, not least some kid from West Texas named Robert E. Howard. How did you happen to (re)discover this guy, who was already largely switching from fiction to non-fiction when guys like Rafael Sabatini where just getting started?

In high school I loved a biography about Hannibal of Carthage written by Harold Lamb, and I saw that he’d written some novels. I was hoping he’d written one about Hannibal. I didn’t know history well enough at that point to be certain a collection of tales titled The Curved Saber couldn’t possibly be about Carthaginians, which is a good thing, because otherwise I might never have checked out a hardback with nine amazing novellas of Khlit the Cossack. They were, and are, so very, very good. The only thing I’d read that could possibly compare were some of the Lankhmar stories. I actually liked these historicals better, and thought they were more consistently excellent.

I am plowing through Lamb’s Khlit the Cossack stories right now, and firstly, OMG are these good – in just one volume we go to Alamut, the hidden fortress of the newly restored cult of Assassins; the trade city of Samarkand; the (booby-trapped) tomb of Ghengis Khan, the vast, Uighur fortress-city of Sianking, visit a mammoth graveyard in the Siberian tundra and learn the secret of Prester John. You could easily imagine Conan, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, or any number of characters by Keith Taylor, Glen Cook or even a Joe Ambercrombie there (or Dabir & Asim, by some guy named Jones). And yet, not a lick of magic…

I used to wish Lamb had done fantasy, but why complain about the wonders we have? He found joy in discovering the hidden details about how ancient eastern and middle-eastern cultures worked, and loved presenting them to us in an engaging way (without ever slowing down the story to impress us with his depth of knowledge). If he HAD written fantasy, modern readers would be a lot more familiar with him, of course. I feel like no matter how much I jump and shout about how great he is people don’t pay attention; those few who do usually start to jump and shout themselves. Everyone else keeps reading fantasy novels and doesn’t take the tiny side-step over to try him out.

And for you? How much does history permeate your historical fantasy?

I strive to be true to the feel of the original fiction of that culture and time. I may not use the exact spells that turn up in The Arabian Nights or the Shahnameh, but I work to emulate the KIND of spells and monsters that might be there. As it happens, a whole lot of cultures have played with the Arabian Nights over the years; some of the fables have Chinese origins, and some may be additions from the French, and of those definitely from the Middle-East many are written centuries apart, originating from very different societies. If all the tales have a similar gloss it’s because those who came to play there fell in love with the feel of them and wanted to try something of a similar ilk. I wanted to play with that same tradition.

I love this last line, sooo much. Why do we always feel like there is only “original” or “derivative” when for millennia, writers have proudly fit themselves into myth cycles and traditions? Shouldn’t fantasy be doing both?

Absolutely, but we can’t just wander in like clueless dogs walking through the flower bed — we have to honor what’s come before and treat it with respect.

Definitely. And, of course, the trick is that if you want to be part of a tradition of writing that includes Howard – or Tolkien, because they are both men concerned with “the matter of the north” – you can’t just be reading them: you have to bury yourself in the tradition. In that case one that goes back to Beowulf and the Eddas, the Kalevala and Tain bo Culaigne. You followed the Howard and Lamb trail a different way, to the lands of Caliphs and caravans.

To do that, I immersed myself not just in secondary sources, but primary sources – at least through translation, which means there’s still one barrier removing me from them. A number of great travelogues came down to us from Arabian travellers, and I work to simulate much of that tone, which is both formal and strikingly direct. I keep my modern audience in mind, though: many of the ancient writers invoked prayers or mention God multiple times upon every page, sometimes within every paragraph, followed by one or more of his ninety-nine names, and I think most readers would find that distracting.

This sets us up to really talk about Dabir & Asim, which is easy, because I love these guys, and I love their world. Now that I’m reading Lamb, I feel like D&A are a bit of a love-letter to both his adventures, the Arabian Nights, and maybe…the same Ray Harryhausen Sinbad movies I watched over and over growing up. Is that fair? And if I’m wrong, let’s try: “Howard, what inspired you to set your stories during the height of Caliphate?”

Oh, that’s completely fair. One of the earliest movies I remember seeing in the theaters is the second Harryhausen Sinbad movie, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (for the record, the other one is The Four Musketeers, which may explain a lot about me).

It explains a lot about any Gen-Xer worth their salt, but go on…

Lamb wrote from non-western viewpoints with some frequency; he was particularly taken with the Arabs, whose histories and letters he found far more perceptive, humorous, and insightful than what he described as the “monkish” and dull histories from the side of the Crusaders. I’d read a novella of his narrated by Khalil el Kadr – a character who later joins forces with the hero from Lamb’s great Durandal trilogy – and shortly thereafter read a wonderful Robert E. Howard historical narrated by Kosru Malik, and I knew, then and there, that I wanted to write something in a similar vein.

But I didn’t want the late era Byzantine period of the Arabian Khalil el Kadr or the era of the Chatagai Kosru Malik – I was attracted to the Arabian Nights, for obvious reasons, and because I had loved the 50th issue of Sandman, which featured Harun al-Rashid as a central character. Harun al-Rashid and his advisor Jaffar both turn up in several tales in the Arabian Nights, and both are portrayed quite sympathetically – perhaps more sympathetically than the historical record actually shows, at least in the case of Harun al-Rashid.

Anyway, there were the caliph and his friend the vizier in the tales, and as an added enticement, there was a lot more historical material about their era than others, which meant research would be simpler. I could play with conceits from the tales, as well as portray people who’d been in them.

Most importantly, I could hear Asim’s voice. I’ve rarely known any character so quickly (apart from Ortok and Kyrkenall) — not just who he was, but how he would speak and present his stories.

In short form, the answer is yes, every time I write about Dabir and Asim it’s a love letter to the Arabian Nights, and Harold Lamb, and at least that middle Sinbad movie, and a huge tip of the hat to Robert E. Howard’s Kosru Malik. I got even more specific about how much I owe to that character in an essay I wrote for the upcoming book from Rogue Blades Entertainment, Robert E Howard Changed My Life.

And now I have to go back and find that Howard tale! Such a burden!

It’s “The Road of Azrael,” and the easiest way to get hold of it is in the Del Rey collection titled Sword Woman, edited by Rusty Burke, with introduction by Scott Oden and afterword by yours truly.

Scott Oden (see last month’s column) and you? Hmm… I’m detecting a pattern between my reading interests and my interview subjects. Go figure.

Did you know he introduced me to both my editor AND my agent?

See what I mean? “World-building” is as much a part of historical fiction as it is fantasy – and even our stereotypes tend to focus on our own culture’s past. So even if readers think they know about medieval Europe, Byzantium and the Caliphate are as alien and exotic as Gondor and Arrakis. Could you describe your process? When you set out to write about Dabir & Asim what are the sorts of things you are looking to weave into your fiction to make the literary world feel “real”?

It’s kind of painstaking, to be honest. I have a huge shelf full of books about the time period and it still isn’t enough. At this point, after nearly twenty years, I’ve internalized a lot of the cultural and societal details. But I’m worried even now about getting things wrong every time I get away from topics I’ve already researched. It’s not my culture, or my religion, and because of that I work very hard to treat the characters with respect and to show the good and bad of their world through their eyes, not mine.

If you know the historical period the most important thing to do is to make your characters real people, and not stereotypes. In adventure fiction like this, I can’t help but be working with SOME stereotypes, like the brilliant investigator or the scheming wizard and the like, but I never default to the overt and ugly preconceptions.

As far as being true to the period, Asim is a man of his time, so he’s a little sexist, especially early on. He’s as loyal a friend as you could want, a perfect gentleman, and has a big heart, but in his youth he thinks women aren’t much worth listening to. As a result, for a good portion of the first novel he completely misses the fact that a young woman, Sabirah, is much brighter than he is.

The problem with creating a flawed first-person narrator is that you’ll occasionally find people who think YOU, the writer, espouse the viewpoints stated by the narrator. I still recall stumbling upon an online reading group that had stopped reading The Desert of Souls because they thought I, Howard, was a misogynist, and they couldn’t understand why Sabirah was being ignored, for she was obviously quite clever. It confounded me then; now it amuses me.

Hannibal of Carthage… er Hanuvar of Volanus, by Darian Jones.

I suppose it is a complement to how well you “sold” the character. Changing gears slightly, how did the process of creating Dabir & Asim’s Dar-al-Islam differ from, say, creating Hanuvar’s analog to Rome and Carthage? Or does it? Are there things you feel free to do in a “Rome-analogous” world you wouldn’t let yourself do in a quasi-real Baghdad? Why?

With Hanuvar I don’t have to worry about accidentally getting something wrong about another society and culture. There’s a tremendous freedom in being able to set the history books aside, although I’ve read scores of material about Hannibal of Carthage and the second Punic War, which are huge touch points and inspirations for the Hanuvar tales. It’s much easier for readers to visualize a setting if you can present it to them and they realize, oh, this looks like a pirate movie, or like Ancient Greece, even if it isn’t, quite, something Robert E. Howard knew very well when he constructed his Hyborian Age civilizations.

Your Hanuvar cycle is very-much sword & sorcery whereas Guy Gavriel Kay’s work very much is NOT, but I do feel like there is an interesting analog here of having seen a great moment in history that doesn’t quite play-out as we might, so, if we change the names we become free to wonder…

We’re certainly very different writers with some different interests, but you’re right, we both get to play what ifs, with the advantage of drawing inspiration from historical settings close enough to our own that it’s easy to follow along with the changes we’re making. And not only can I be inspired by real events and people but not be locked into what they did and what happened, I can use magic and monsters.

What are the difference between the real world and the invented one of these tales?

Hannibal’s Carthage rarely seemed to deserve Hannibal’s loyalty, so I gave Hanuvar a city that did. And since we usually think of Rome from its empire days, but Hannibal fought it when it was an expanding republic, I made my Rome analog an Empire. There are numerous other little changes.

The darkest aspect about the whole Rome versus Carthage conflict is what the Romans did during the Third Punic War. When they surrounded the city they told the Carthaginians they would only discuss terms if Carthage surrendered its weapons of war. When they did, the Romans proclaimed that the Carthaginians must also abandon their city and burial grounds and march away to found a new settlement.

That’s when the people of Carthage reconciled themselves to a fight to the death. They had no weapons left, so they fashioned bows from trees within the city and strings from the hair of their women. Astonishingly, they held the Romans back for three years, and when the Romans finally breached their walls the Carthaginians fought block by block, house by house. The last group of surviving resistors retreated into a burning temple rather than be captured. As if a near total extermination wasn’t enough, after the Romans marched a few hundred prisoners into slavery they sowed the fields with salt so nothing would ever grow there again.

Hannibal was long dead by the Third Punic War, but in the Hanuvar tales, the Roman analog has moved against his beloved Volanus in his own lifetime. Hanuvar’s engaged in an ongoing struggle to find the few thousand survivors that the Dervan Empire led off to slavery, and get them safely to a distant colony. He knows his luck will probably run out, but, much like Hannibal, he’s not just the smartest man in the room, he’s probably already ten steps ahead of everybody even three cities over.

Not many history books are exciting enough to get S&S style covers,

but Lamb’s are — while still being actually *good* history.

Why Hannibal? I mean, crossing the Alps on an elephant is cool, and all, but…

Hannibal was something of a superman. Unlike almost all other generals of antiquity, his was not a warfare motivated by the acquisition of territory, but to halt the Romans, who were poised to conquer not just his homeland’s colonies, but his homeland itself. Given that the Romans ended up exterminating his people, it seems like he was right to challenge them.

You’ll find lots of grand technical discussions about his victories at Cannae, Lake Trasimene or the other battles he waged, defeating forces two or more times his own size. What you might not find is a discussion of countless other clever stratagems: for instance, the time he tricked the Romans into fighting an army of oxen, or the time he arranged for a delivery of Roman supplies to be sent to his own troops, or how he got the Romans to recall their one effective commander in the field (Fabius) by laying waste to every farm for miles except those owned by Fabius. Hannibal was a professional soldier in an age of amateurs, and to defeat him the Romans had to develop a professional soldier class of their own that helped lead to the dissolution of the Republic itself.

After the war Hannibal rose to power in Carthage and enacted a series of sweeping reforms that eliminated vast layers of graft and corruption — enough that he was able to pay off the crippling fine imposed by Rome upon his city decades before it was expected. I especially like that he changed the lifetime rule of Carthaginian senators so that they had to be elected by the people they represented every two years!

(There happens to be a great Hannibal book by some guy named Harold Lamb that talks about all this stuff. Ernle Bradford’s Hannibal book is also quite excellent.)

His dry, laconic wit, his dedication to his people, his stunning brilliance and ability to think on his feet, not to mention his honor, remain immensely appealing to me. Once I had immersed myself in the hardboiled writers I realized that Hannibal himself was a hardboiled character, a man dedicating his life trying to do the right thing for an entire band of people that never fully appreciated his sacrifice and dedication. Fate and even the gods seemed against him, but through skill, intellect, and by virtue of astonishing determination, he turned impossible situations to his own advantage again and again.

The Ring-Sworn Trilogy is your current novel series. This is a pretty sweeping, gonzo universe: Zelazny’s Amber meets the Three Musketeers, with little notes and hints of everything from Moorcock’s Multiverse to old legends of Faerie. (Clearly, I’m a fan.) My point is, that when the very nature of a world’s topography can shift and change from moment to moment, you’re free to do whatever you want in terms of world-building, but as an author you have to keep the audience believing in these people and this very unusual world. Did you establish a set of “rules” for yourself as to how this world works, on a practical level, the way you might with 9th century Baghdad, or no?

Absolutely. I had to know the deep secrets about the world, and I had to have a handle on the magical powers, and I had to know the society. I put a lot of time into constructing how the warrior corps worked; I think the construction of the Altenerai oath and their swearing-in ceremony might have been the longest amount of time I’ve ever spent on such a short number of words.

Now, be honest… with the greater level of fantasy, do you find that when you get stuck with a plot point it’s easy to say “because magic” to get out of it?

Hah! No. I try never to do that. I hate magic that has no boundaries, although I also dislike a magic system that’s completely codified. If there’s ever a moment where magic is suddenly used in a way the characters haven’t seen used before, then I try to make them just as shocked by it as the readers would be, and to have it make an impactful change going forward.

In our interview, Scott Oden said that if magic isn’t wild and at least a little unpredictable for all involved, it’s just not magic, and certainly not magic the way historical people looked at it. Agree?

That’s certainly how I feel about it. I don’t find magic interesting if it’s just science by another name; magic shouldn’t ever feel safe and certain. But then I’m not really much into whimsical stories. I think some people really dig highly detailed magical systems and lists of spells and all that, and that’s just never been my thing.

Volume Three of The Ring-Sword Trilogy… coming as

soon as I let Howard stop answering questions so he can go write

Part of what lured me in with For the Killing of Kings, were the characters. They are all very different, and they all have a lot of heart. (And OMG, there isn’t a lick of grimdark about any of it!!!) But they are also, in a sense, very modern. I think one of the “great lies” of fiction is how we handle characters, if we want them to be appealing to modern audiences. Truth be told, if an author wrote a completely authentic ancient Roman or medieval lord, let alone something like an Aztec priest or Assyrian despot, they’d lose their audience. These civilizations had mores and customs that are alien to our own and fly in the face of modern notions of “correctness”. Personally, I’d rather come to terms with a character who can comfortably watch someone skinned as an offering to the Maize Maiden then listen to a “woke” medieval knight – even if that character probably has values more like mine.

The Ring-Sworn world is culturally advanced – or rather, parts of it are. The kingdom is a matriarchy and magic comes to both genders, so we have female knights and sorceresses, female commanders and leaders – in a way that just wouldn’t work with Dabir & Asim or Hanuvar, but works beautifully and believably in the world you created here. Can you talk a little about how you handled ideas of gender roles in the books?

While I put a lot of thought into those roles, I didn’t want to make gender topics the focus of the book; the racial and gender equality of the central society is just a low-key matter of fact. In the foreground are a large number of clever women leaders and warriors, starting with the central protagonist, Elenai. Prominently positioned women are such an ordinary part of this society that the characters themselves don’t comment upon it. You might also notice a couple of the heroes are likely on the spectrum, and that another is almost surely aromantic, but I don’t dwell on that, I just have them doing what they do to save their friends and society.

It’s a fantasy world, so why create a society with the gender and racial and sexual prejudices that constantly dog our own culture? I wanted those problems to be so foreign that they weren’t really even topics of discussion. Almost all of the central figures of this series are part of the Altenerai military order, and all they care about is unraveling the rot at the center of the kingdom and whether a colleague has their back in the foxhole. When they’re facing betrayal and almost certain death, why would they possibly care about their friend’s lover’s sexual identity?

Again, though, this is all background. Apart from Kyrkenall’s ongoing search for the lost Kalandra there’s not much on-screen time given to romantic/sexual stuff, unless you’re with Rylin in book one. He starts the series with a flawed understanding of his duty and responsibility, using his position to cater to his own gratification. Fortunately Varama sees the potential in him and helps shape him into a better human being.

I also thought you introduce a fascinating contrast in the Naor, who are decidedly regressive and sexist, and this allows the introduction of a sort of transgender character, that runs against the way we normally think of such things today, but fits very well in an iron-age culture.

In order to hold power in his society, Vannek has to declare himself a man, though he was born a woman. Maybe that’s not the starting point for many transgender people today, but he shares this in common with them: he does NOT think of himself as a woman in disguise; he thinks of himself as a man.

No, but it brings home the fact that gender and issues of gender identity have been both a challenge and handled in different ways – to differing degrees of success – by different cultures. Here we have a very misogynistic society but also a very authoritarian one, so once Vannek is declared a man by their king, that’s it, he is (at least, officially), and yet at a price of constant wondering at how he’s being judged – and the unspoken point to the audience that this is only possible for him because of his place in society. What happens to the baker’s daughter who decides she’s the baker’s son? I think, though the mechanism is different, that is relatable without making Naor society suddenly modern Western society.

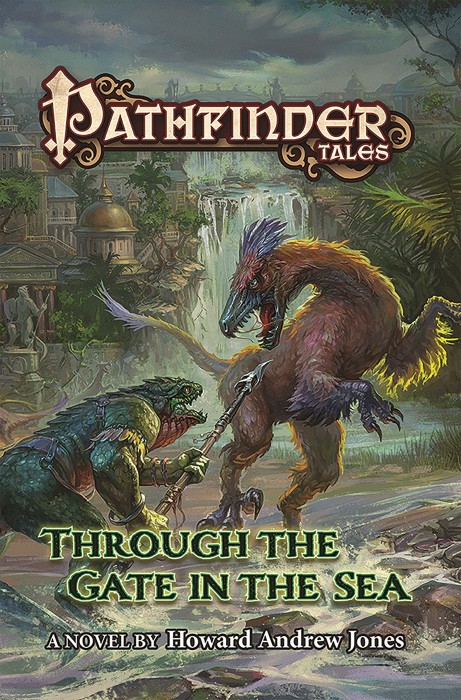

You also wrote four Pathfinder novels. I know that sort of spec-work is where a lot of author’s cut their teeth or where some go to “play”, but for me, it seems daunting! You can’t get more “High Fantasy” than D&D/Pathfinder-based worlds: with so many hands involved, trying to create a setting that hits so many gamers’ desires, it’s a “hobo stew” setting. Then you, as a writer, must fit yourself in, and tell a story in this “conglomerate” world. From a creative point of view, what’s that like?

Paizo was really good to me. When I was approached for the gig by James Sutter, he encouraged me to stick to my sword-and-sorcery roots, so I did. I saw some readers complain that the first book lacked enough healing magic, but I wrote the way I used to game master, with a lower magic feel as the default. I think healing magic, and the possibility of resurrection, steals a lot of threat and power from gaming and game fiction alike.

Once I understood that a lot of game fiction readers assume that everyone plays their games with the same high magic feel, I included healers in the make-up of the parties in the novels – and usually got those healers killed or separated so I could continue to make magical healing a rarity.

I was given a great deal of creative freedom to make proposals. The thumbnail had to be thoroughly considered and then a detailed outline approved, but I didn’t feel constrained. I particularly loved the opportunity I received in the last two books, which are set down in the tropics and are bereft of many of the bog-standard game fiction things. In those two I significantly downplayed the whole elf and dwarf and orc tropes and high fantasy feel and made the conflict much more about racial and national identities.

I promised you Lizard Men in this column’s title…

here’s one now. There’s more if you read the novel.

The chief non-human “monsters” the characters interact with in the last two are lizard folk, and I had a great deal of fun bringing them to life. I’m pretty pleased with them, honestly, starting with Beyond the Pool of Stars. If the line hadn’t gone on hiatus I’d hoped to pitch Paizo on not just a sequel, but a tightly connected trilogy, something the line never tried.

In the Pathfinder novels you write about a variety of non-human characters, and in Ring-Sworn we get some of my favorite secondary characters, the ogreish Kobolin, with their very…um…particular…social rules and the intelligent feathered-serpent ko’aye. Do you find it easy writing non-human characters? Does the character evolve and from that the rules of how its species acts, or vice-versa?

I enjoy writing non-human characters and keep slipping them into my books, and I always try to give them a different perspective because that’s fascinating to me. I loved how Spock was used in the original Star Trek to comment upon human behavior from an outsider’s perspective and I certainly do the same with my characters, whether they’re the lizard folk in my second set of Paizo novels or the kobalin and ko’aye.

I guess I can say that Ortok the kobalin is one of my favorites of the characters I write. I rarely have to revise any of his dialogue because I almost always know exactly what he’s going to say and how he’s going to say it. When I drop him into a scene, it’s almost like taking dictation, something I wish I all my experience writing was like.

I suppose, this whole interview has been about creating audience “buy in” – whether it is the Russian steppe or the Shifting Lands, 8th-century Baghdad or Golarion, the audience has to be able to believe and disappear into the world your are presenting. If I put you on the spot and ask, “what’s the secret sauce” will you say something more than “51 herbs and spices”?

In its simplest break down, it’s about creating interesting characters going to interesting places for interesting reasons. In my case, more expansively, I try not to slow down the narrative for exposition, rather, I blend that detail into the events; if a longer explanation is necessary, I try to wait to do it until the reader is eager to know the information. I hate reading a story where the information is all front-loaded, whether it be societal details or a character’s entire back history, and I try not to write that way. I just want to get on with the story, you know?

And as much as I care about certain topics, I hate it when I’m beat about the head with them. There’s a vast world of difference between subtle issues underlying a great adventure story versus a story that’s solely centered around a message that MUST BE communicated, as when you compare a wonderful old Star Trek episode like “The Doomsdsay Machine” with the Trek episode where two races on a planet are half black and half white on opposite sides of their body. The former is a fantastically tense, haunted character and action piece with subtext about the danger of weapons too powerful to be contained whereas the latter is nothing BUT a blunt, painfully obvious discussion of racial prejudice.

Finally, I know the Ring-Sworn is drawing to an end… you just debuted the cover! Any ideas what’s next?

So many ideas! I’ve working on pitches for several new series, and I’m always plotting out new adventures for Dabir and Asim and Hanuvar. Right now the revision of the third Ring-Sworn book has to be front and center, but that should be wrapped up in the next month or so, and then my agent and I will sort through the pitches and figure out which one to shift into high gear.

My wife and son especially want me to work in time to write the third Dabir and Asim novel, and way on the back burner I’ve been reacquainting myself with the original outlines. Eight years ago my plans were a little too ambitious for what I could actually pull off, but I think I might be able to manage it, now. We’ll see.

Greg is a native Chicagoan with a background in journalism and history. While in university, he began researching the martial arts of Late Medieval and Renaissance Europe. After working in marketing and corporate communications for a decade, he lost his mind and opened a small, non-fiction press (www.freelanceacademypress.com) dedicated to medieval studies, and opened Chicago’s only full-time European martial arts school to house the Chicago Swordplay Guild, which he had founded in 1999 (www.chicagoswordplayguild.com). As a fiction writer, in recent years he has published a growing number of short stories, and has the obligatory unpublished novel manuscript sitting on his hard drive.

Greg lives with his very tolerant family in the Chicago suburbs. His most recent article for us was an Interview with Scott Oden.

What a great interview. This hits at the perfect time for me. I’m over halfway through Mike Duncan’s History of Rome podcast.

The late republic era has been my favorite so far. I’ll add Harold Lamb’s Hannibal book to the wish list.

I’ve read the first two Hanuvar stories. The Way of Serpents has been my favorite so far. Now that i know he’s based on Hannibal i’ll be coming at the stories with a much clearer image of the world.

Smashingly good interview! I could talk about this stuff all day. Howard always has interesting things to say.

John,

If you missed the last two with Christian Cameron and Scott Oden, they were pretty awseome, too, but this one was epic — this is after Howard and I cut about 1000 words for length reasons (not to worry, it will go into another column). This could easily have been 1000 words of geek-out!

Glenn,

I’m a huge Hannuvar fan myself — my favorite, by far, is The Second Death of Hannuvar in Tales from the Magician’s Skull #3.

An excellent interview!

If you’re looking for another of Howard’s Hannuvar stories, we had one in the 10-year issue of Heroic Fantasy Quarterly : http://www.heroicfantasyquarterly.com/?p=2735

AND we’ll have a Dabir and Asim story in issue #45 in August.

Wow, that’s a gorgeous cover for When the Goddess Awakes. LOoking forward to that. ALso glad to hear that Dabir and Asim are roaming about again! Great news.

And if someday I can buy an entire standalone collection of Hannuvar stories, that will be no bad thing indeed!

http://ebooksunltd.blogspot.com/2019/09/little-lost-lambs-by-harold-lamb.html

Little Lost Lambs, by Harold Lamb. I didn’t believe it. Really. Now all I have to do is find a copy.