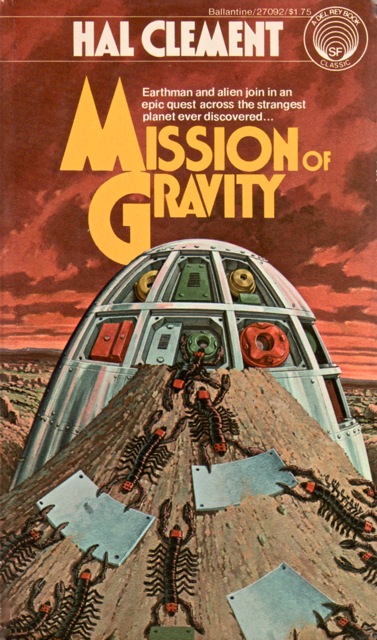

Mission of Gravity by Hal Clement

Once upon a time, there was a strand of science fiction called hard science fiction, dedicated to the exploration of scientific puzzles and more-or-less accurate studies of the physical sciences. The roots of this strand would seem to lie in the technology-focused stories of Jules Verne. Sometimes there’s an adventure involved (Larry Niven’s Ringworld), sometimes not so much (Robert Forward’s Dragon’s Egg). Whatever the type of story, in hard sf it was the science that occupied center stage. One of the foremost practioners of this style of science fiction was Hal Clement (1922-2002).

Once upon a time, there was a strand of science fiction called hard science fiction, dedicated to the exploration of scientific puzzles and more-or-less accurate studies of the physical sciences. The roots of this strand would seem to lie in the technology-focused stories of Jules Verne. Sometimes there’s an adventure involved (Larry Niven’s Ringworld), sometimes not so much (Robert Forward’s Dragon’s Egg). Whatever the type of story, in hard sf it was the science that occupied center stage. One of the foremost practioners of this style of science fiction was Hal Clement (1922-2002).

Hard science fiction still exists, obviously. Cixin Liu, Vernor Vinge, and Greg Bear are all writing science-heavy stories. Now, though, there’s less of the puzzle-solving variety, and a greater emphasis on exploring the effects of science on people and society. Larry Niven won a Hugo for the story “Neutron Star,” which hinges on its hero understanding how tides work. I’d be curious if anyone’s written a story like that in the last ten or twenty years. In his overview of The Best of Hal Clement, John O’Neill examined the possible causes for the decline in popularity of hard sf.

Clement published his first story, “Proof,” in 1942, while still an astronomy student at Harvard. After the Second World War (during which he flew 35 bombing missions as a B-24 pilot and co-pilot) he taught astronomy and chemistry at Milton Academy for many years. His first novel, Needle (1950), the story of a symbiotic space detective, was written in response to William Campbell’s claim that a true sci-fi mystery couldn’t be written. His third novel, and today’s subject, Mission of Gravity (1954), is an exemplar of hard science fiction at its diamond-hardest.

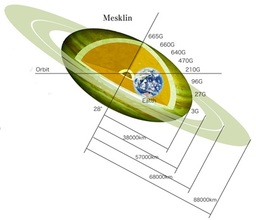

A valuable human probe has malfunctioned while surveying the planet Mesklin. It can’t lift off, and local conditions prevent its recovery. The difficulty lies in the nature of Mesklin: it is a massive Jovian planet that spins so fast it isn’t spherical, but oblate. Around the equator, where the gravity is a mere 3g, Mesklin measures 48,000 miles. From pole to pole, it’s about 20,000 miles and the gravity is a mind-blowing 700g. The mean surface temperature is -170 °C. Even in the relatively low-gravity equatorial zone, humans must rely on power-assisted suits to move. Other than the specially-built probe, nothing at hand can survive the rigors of the polar zone where it is stuck.

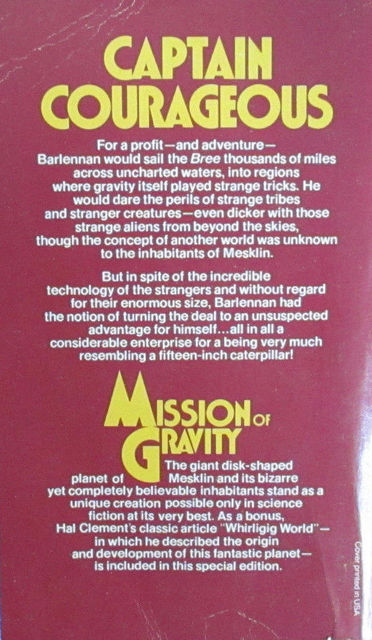

The only thing the humans can do is make a deal with some of Mesklin’s natives to secure the probe. As luck would have it, the first Mesklinite the humans make contact with is Barlennan, the wily captain of the merchant raft Bree. He is the model of a hard sf hero: a competent man with a rational approach to problem-solving. As for problems, there are plenty along the tens of thousands of miles he has to travel to reach the downed probe.

The only thing the humans can do is make a deal with some of Mesklin’s natives to secure the probe. As luck would have it, the first Mesklinite the humans make contact with is Barlennan, the wily captain of the merchant raft Bree. He is the model of a hard sf hero: a competent man with a rational approach to problem-solving. As for problems, there are plenty along the tens of thousands of miles he has to travel to reach the downed probe.

Despite having thin characters, some fairly dry dialogue, and dated science (when did anyone last use a slide rule to calculate gravitational effects?), Mission of Gravity is a terrific and quick read. Perhaps the best reason to read science fiction is to learn how big and wild the universe is. Even with Clement’s lukewarm prose, the sense of wonder in MoG — at the enormousness of the planet, the powerful forces that shape it, and the creatures that have evolved on it — is never less than powerful.

Mesklinites are hydrogen-breathing, red and black, centipede-like beings. From a relatively high gravity region, Barlennan and his crew are about eighteen inches long and rise only and inch or two above the ground. Where they come from, a fall of six inches is certain death. The walls of their homes are no more than three inches high. Heights terrify them, and concepts like throwing and flight are completely alien to them.

When Barlennan is lifted onto the roof of a tracked vehicle by the human, Lackland, we see how the world looks from six feet up to someone used to seeing it from only an inch. There is fear, but it is quickly supplanted by something else:

The fear might have — perhaps should have — driven him mad. His situation can only be dimly approximated by comparing it with that of a human being hanging by one hand from a window ledge forty stories above a paved street.

And yet he did not go mad. At least, he did not go mad in the accepted sense; he continued to reason as well as ever, and none of his friends could have detected a change in his personality. For just a little while, perhaps, an Earthman more familiar with Mesklinites than Lackland had yet become might have suspected that the commander was a little drunk; but even that passed.

And the fear passed with it. Nearly six body lengths above the ground, he found himself crouched almost calmly. He was holding tightly, of course; he even remembered, later, reflecting how lucky it was that the wind had continued to drop, even though the smooth metal offered an unusually good grip for his sucker feet. It was amazing, the viewpoint that could be enjoyed — yes, he enjoyed it — from such a position.

|

|

That incident sets the tone for the rest of Barlennan and his crew’s adventures. Throughout their long voyage to the polar region, they are confronted with things and people that are unfamiliar, even disturbing, to their long-held conceptions of the world. After some initial shock, they buckle down and figure out how to face them, overcome them, or take advantage of them.

While they meet various obstacles to reaching their objective — primitive barbarians; low-g evolved giants; canny city dwellers with sailplanes — the greatest one is the planet of Mesklin itself. The methane oceans are given to shrinking drastically at certain times of the year, and the terrain experiences extreme changes as a result. Much of the landscape is featureless, making it difficult to keep track of one’s location. Just short of the stranded probe, they encounter something so seemingly insurmountable — a sheer, thirty foot cliff — that they are almost forced to give up.

Despite giving us little insight into Mesklinite society or psychology, Clement manages to bring his crew of bold explorers to life. Well-traveled, they have acquired knowledge and experience enough to face every osbtacle with rationality and aplomb. Barlennan is a canny plotter, with secret plans for his future dealings with humans. First mate Dondragmer comes to life as well. While not as bold as his captain, he possesses a sharper insight toward problem-solving, and steps to the fore several times in the story. It’s fun to come across main characters who are calm, skillful thinkers for a change.

The weakest element of Mission of Gravity is the “unalien” nature of the aliens. I love their personalities, but they come across as (human) sharp-eyed Yankee traders. Clement’s focus was on building the planet and designing the biology of its flora and fauna. As the reader would see the world through the Mesklinites’ eyes, Clement decided, I suspect, to make them think not much differently than humans. The closer to our own thinking, the more sense it would all make. I get it, but believe the story would have benefited from a little more strangeness, a little more “alienness” from the aliens.

When I was a kid, this was a book most of my sf-reading friends read and strongly recommended. For whatever reason, it’s taken me forty years to get to it, and I’m glad I did. There is contagious joy in Clement’s building of Mesklin and his explaining the science behind it. You want to know — you need to know — how things work, and how Barlennan and company will save the probe.

This is some really heavy-duty stuff that’s tough to follow. Clement wrote an essay called “Whirligig World” to explain even more of the science. He starts with how he first conceived of Mesklin after reading about the orbit of the binary star 61 Cygni. After that, things start getting complicated, but his obvious excitement over his creations made me want to understand what he was saying. He explains how he arrived at the planet’s orbit, its gravity, and why he gave it methane seas and a hydrogen atmosphere. It is hard to follow, but it’s fascinating. I was never great in science in school, but I think I would have loved it if Hal Clement had been my teacher.

I’m not sure if there’s much room in modern science fiction for a physics-heavy story like Mission of Gravity. It seems as if the engineering roots of science fiction, even more than its pulp roots, have been forgotten or at least put away. A great deal of modern science fiction, derived from games, films, and comics as much as it is from books, seems more intent on looking a certain way than exploring any actual science. It’s not a good or bad thing, but a lot of the writers I grew up reading were as inspired by Clement as by Doc Smith (which is why when someone like Cixin Liu comes along I get pretty excited).

I’m not sure if there’s much room in modern science fiction for a physics-heavy story like Mission of Gravity. It seems as if the engineering roots of science fiction, even more than its pulp roots, have been forgotten or at least put away. A great deal of modern science fiction, derived from games, films, and comics as much as it is from books, seems more intent on looking a certain way than exploring any actual science. It’s not a good or bad thing, but a lot of the writers I grew up reading were as inspired by Clement as by Doc Smith (which is why when someone like Cixin Liu comes along I get pretty excited).

Mission of Gravity (and its sequel, Starlight) is readily available. It’s still easy to find used. For a reasonable price you can get the omnibus, Heavy Planet, from Orb Books, which includes both novels, a pair of short stories, and “Whirligig World.”

I’ve read that a lot of Clement’s books suffer from terminal dullness, focusing on the science to the exclusion of everything else, but that’s not the case here. Mission of Gravity is good fun that’s bound to fire up the science-y parts of your brain. And you’ll never look at a centipede the same way again.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about Western movies.

There’s a nice mention of this novel in Michael Chabon’s new book, MOONGLOW.

Indeed … I think it even mentioned Astounding.

MOONGLOW is a very fine novel, and while it’s not SF, it’s of considerable interest to an SF reader, I think.

(And, I’ve argued, if APOLLO 13 can get a Hugo nomination, and, quite possibly, HIDDEN FIGURES, why not MOONGLOW? (Not that I nominated it myself.))

I think I’ve seen a couple puzzle stories of the type Fletcher mentions recently, but surely there are fewer these days. I’ll try to remember them later …

This is one of those novels I have been meaning to read for years, mainly because I have often heard it compared to The Foundation series and Dune. I believe I tried reading it about 15 years ago but for some reason it didn’t grab my attention. Eventually I will try again.

It really is one of the all-time great SF adventures; the problem and its solution are so enthralling that, as Fletcher says, Clement’s stylistic faults don’t matter much.

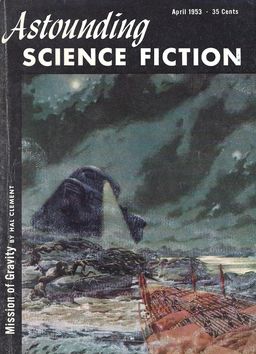

A classic, a great SF novel, and sadly forgotten by readers of the 80s and after, perhaps even before that. This is a personal favorite, I read it in Astounding in the issue shown (and after, I think it was a serial) with the original illustrations. Fabulous. I’ve reread it several times, and with this reminder may do so again.

@Bill C. – Cool. From what I’ve read, Moonglow sounds interesting – I probably need to pick it up.

@Rich H. – Let me know if you remember them. I’d like to see how the style’s being approached today.

@Amy B. – It’s not like them at all, but don’t let that deter you.

@Thomas P. – Like you wrote last week, “It’s flippin’ awesome!” Is Starlight worth the time? I’d love to Dondragmer take the helm stage with Barlennan in the command center.

@RK Robinson – I’ve long come to accept the reality of older works being forgotten in the face of modern tastes, the vast quanity of new material, and the passage of time. It just makes me sad/mad/annoyed when good, primary texts are lost and not replaced by anything comparable.

Yes, it was serialized over four issues in 1953. I’m wasn’t kidding about all my sci-fi-reading friends having read it when I was a kid in the seventies. How I avoided it, I don’t know – but I knew the basic setup and about Mesklin and the Mesklinites. It was just something in the sci-fi air.

I read Mission of Gravity back in like 9th or 10th grade. I remember liking it quite a bit. I started the sequel, but didn’t get into it for reasons that I have long since forgotten.

Incidentally I have been told that the serial version of MISSION OF GRAVITY is actually longer than the book version.

Now all we need is a major revival of George O. Smith’s Venus Equilateral stories. Nuts and bolts for days and days…

Neat classic story and one I’ll confess I’ve never got around to reading. – BTW – can find on internet archive.

Today’s “Hard Science Fiction” is tomorrow’s “Steampunk”. Like some hard scifi, not knocking it, but just observing.

[…] (1974)Ted Chiang: Exhalation (2019)*Arthur C. Clarke: The City and the Stars (1956)Hal Clement: Mission of Gravity (1953)Samuel R. Delany: Babel-17 (1966)Philip K. Dick: The Man in the High Castle […]