Adventures In Benign Cults: Parable Of the Talents

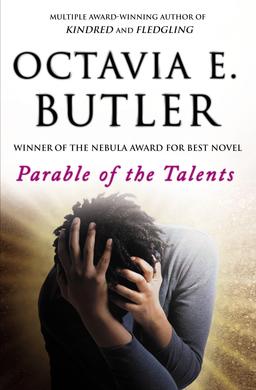

If a book vaults from mere printed text to a work of serious literature by virtue of posing a question, and then exploring it through the course of the story, then Octavia Butler’s The Parable Of the Talents fits the bill very neatly indeed.

If a book vaults from mere printed text to a work of serious literature by virtue of posing a question, and then exploring it through the course of the story, then Octavia Butler’s The Parable Of the Talents fits the bill very neatly indeed.

Its primary question seems to be discovering meaning in what is for Butler a necessarily godless world, but it takes on secondary questions galore. Among these: what is the difference, if any, between a religion and a cult? How fine is the line between healthy determination and destructive obsession? And just how often do we reject others simply on the grounds that they challenge those (shaky) convictions on which we’ve built our lives? In other words, we blame and hold accountable people who represent our own failings.

Butler has a field day with all of these and more in charting the life of Lauren Oya Olamina, founder of Earthseed, a cult that locates God in change — the concept of change — and sets its sights on the stars when life on earth (or at least in the Disunited States of the 2030s) is nothing but chaos.

Formally, Butler’s Parable Of the Talents (the sequel to Parable Of the Sower) is epistolary work. The story is related through select journal entries, mostly Olamina’s, with other voices interspersed. These include her husband, her lost daughter, and her estranged younger brother.

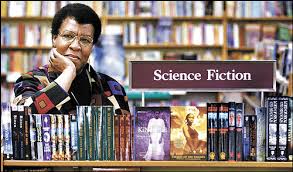

First published in 1998, Parable Of the Talents won the Nebula Award in 1999. Like a good many other Nebula winners (such as The Speed Of Dark, which I wrote about here recently), this is not hard science. If you’re looking for the nuts and bolts engineering or chemistry found in Kim Stanley Robinson or Andy Weir, look elsewhere. Butler’s near-future tale focuses on social disintegration, and its rebirth via the benign (?) cult of Earthseed.

All books have style, but for this reader, Butler comes across much like a documentary photographer, aiming her prose lens without regard to (or interest in) aesthetics. This is a book that shies from the trappings of artistry, at least those outside the bounds of its formal constraints (see above), for fear that mere wordplay might get in the way of larger truths.

Butler also reveals a deep distrust of Christianity. Not that she’s alone. Indeed, one of the great tropes of Sci-Fi and spec-fic in general is its consistent questioning or outright rejection of organized religion. And perhaps I’m misreading: after all, it’s Butler’s leading lady, Lauren Olamina, who truly fears doctrinal Christians — and with good reason, given what befalls her at Christian hands. One or two characters who qualify as “people of faith” come off as kind and decent, but the organized church itself? Butler has not a kind word to say at any point — although she does have a soft spot for Unitarian Universalists.

Butler also reveals a deep distrust of Christianity. Not that she’s alone. Indeed, one of the great tropes of Sci-Fi and spec-fic in general is its consistent questioning or outright rejection of organized religion. And perhaps I’m misreading: after all, it’s Butler’s leading lady, Lauren Olamina, who truly fears doctrinal Christians — and with good reason, given what befalls her at Christian hands. One or two characters who qualify as “people of faith” come off as kind and decent, but the organized church itself? Butler has not a kind word to say at any point — although she does have a soft spot for Unitarian Universalists.

Along the way, Butler re-enacts and repurposes the horrors of the real world’s antebellum slave trade. If her goal was to sow repulsion in the reader, she succeeds admirably.

Thanks to her exhumations of slavery and the Christian identity of those practicing it, hypocrisy becomes the book’s harshest, most recurrent theme.

I’ve heard many argue that in certain kinds of fiction, repetition plays a key role. Think of the joke about the cornpone Baptist Minister who, when asked how he makes certain that his congregants know what he’s trying to impress, replies as follows: “First I tell ‘em I’m gonna tell ‘em, then I tell ‘em, and then I tell ‘em I done told ‘em.”

Parable has a habit of repeating information, though I cannot decide if it’s intentional or not. Key points (and a good many asides) are often repeated many times over, sometimes in closely succeeding pages (or even paragraphs). Much as it pains me to say this, especially about an author who received a MacArthur Fellowship, I cannot think of a book — or at least not a worthy one, which this is—that lends itself so easily to skimming.

Perhaps this also has something to do with its epistolary framework. Because everything is related well after the fact, the action of the book frequently devolves into “mere” history. This, too, is likely intentional, allowing Parable to function not only as the story of Lauren Olamina, but also as the journalistic history of Earthseed as movement.

Perhaps this also has something to do with its epistolary framework. Because everything is related well after the fact, the action of the book frequently devolves into “mere” history. This, too, is likely intentional, allowing Parable to function not only as the story of Lauren Olamina, but also as the journalistic history of Earthseed as movement.

But epistolary fictions need not be sluggish. Think of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or (again) Andy Weir’s The Martian. The Secret Diary Of Adrian Mole is a very speedy read, and Joyce Carol Oates achieves a keening ache of emotion in her short story, “Cousins.” Speaking of short-form epistolary work, everyone reading this should seek out the sly comedy of “Mr. Simonelli of the Fairy Widower” by Susanna Clarke and anthologized in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror Fourteenth Annual Collection from Datlow and Windling.

My Grand Central edition of Parable, from 2000, contains a helpful post hoc interview with Butler. Often, such inclusions are annoying, trite, aimed at a readership unable to formulate questions of their own – and yes, there are “Reading Group Questions and Topics For Discussion,” too—but Butler offers cogent, considered answers to the questions put to her, and makes a lively defense of her authorial choices. Butler herself passed away in 2006, so interviews like this are the closest we’ll now come to learning what precisely inspired her fiction.

Meanwhile, keep an eye on these Black Gate pages for a few authorial choices of my own. Bonesy arrives in the world on September first, and I’ll be running a giveaway here in the very near future!

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” Also available at Black Gate is his serialized novel, In the Wake Of Sister Blue. The first installment may be found HERE.

Away from Black Gate, he is the author of the supernatural quartet, The Skates, Sleeping Bear, Check-Out Time, and Bonesy, all published by Samhain and featuring his semi-dynamic duo of Renner & Quist. His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Unlikely Story, Betwixt, Black Static, The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Realms of Fantasy, Witness, The Beloit Fiction Journal, Talebones, Not One Of Us, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet and many more. In other work, Rigney is the author of the plays Ten Red Kings, Acts of God and Bears, winner of the 2012 Panowski Playwriting Competition, as well as the non-fiction book Deaf Side Story: Deaf Sharks, Hearing Jets and a Classic American Musical (Gallaudet). Two collections of his stories (all previously published by various mags and ‘zines) are available through Amazon, Flights of Fantasy, and Reality Checks. His author’s page at Goodreads can be found HERE, and his website is markrigney.net.

|

|

|

|