Thank Goodness! Why Gatekeepers Will Always Be With Us

Sixteen of your US dollars. That’s what the latest (monster) issue of Black Gate has cost you in these days of fear and crumbling factories. It’s strange, isn’t it? You’ll spend all that money on a collection of fiction and game reviews when the internet is bursting with so much free content. If you go looking right now, you can find a million Sword & Sorcery stories out there that you wouldn’t even need to pirate: the authors, overcome in a delirium of generosity, are only too thrilled to supply them for free.

Sixteen of your US dollars. That’s what the latest (monster) issue of Black Gate has cost you in these days of fear and crumbling factories. It’s strange, isn’t it? You’ll spend all that money on a collection of fiction and game reviews when the internet is bursting with so much free content. If you go looking right now, you can find a million Sword & Sorcery stories out there that you wouldn’t even need to pirate: the authors, overcome in a delirium of generosity, are only too thrilled to supply them for free.

And it doesn’t stop with short-stories! There are more novels waiting for you online than any dozen people could read in a lifetime, along with plays, movie scripts, poetry…

Oh God. The poetry.

So, what’s stopping you? I’ll tell you what’s stopping me: I don’t want to be a slush reader. It is mind-rotting, eye-burning work that actually becomes worse the more of it you do. Like some sort of cumulative poison. And for every great story we read in the pages of Black Gate, there have been several hundred at least that would have had any sane person thinking more and more about drinking that bottle of bleach under the sink. Oh yes.

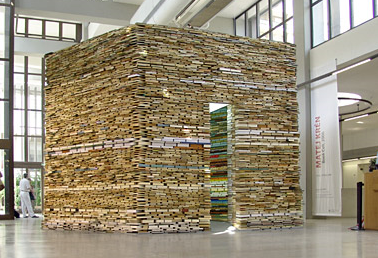

Prague-based artist Matej Kren has created a room made almost entirely of books. It is part of the city gallery of Bratislava.

Prague-based artist Matej Kren has created a room made almost entirely of books. It is part of the city gallery of Bratislava.

But Bellairs was more than that. He was also a first-class fantasist, whose one book for adults, The Face in the Frost, is something unique. Written before his tales for children, on its publication in 1969 it was described by Lin Carter as one of the three best fantasies to have appeared since The Lord of the Rings.

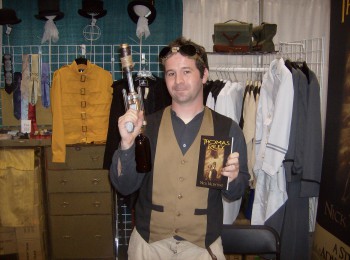

But Bellairs was more than that. He was also a first-class fantasist, whose one book for adults, The Face in the Frost, is something unique. Written before his tales for children, on its publication in 1969 it was described by Lin Carter as one of the three best fantasies to have appeared since The Lord of the Rings. Now that Gen Con is done, it’s time to offer up some final thoughts, experiences, and, of course, games.

Now that Gen Con is done, it’s time to offer up some final thoughts, experiences, and, of course, games. Pulp Adventure Roleplaying Games

Pulp Adventure Roleplaying Games The lead story for the

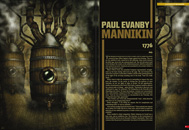

The lead story for the complete artwork comprising all the issues in 2010) is “Mannikin” by Paul Evanby. The story opens in July 1776, the date of American declared independence from British colonial rule (sidenote: the writer is Dutch and the magazine is published in the U.K.). But this isn’t about Ben Franklin or Thomas Jefferson, and doesn’t even take place in the colonies, but rather signifies the irony of a revolution that resulted in freedom for white Protestant male landowners who relied on the exploitation of African-American slaves to maintain economic autonomy.

complete artwork comprising all the issues in 2010) is “Mannikin” by Paul Evanby. The story opens in July 1776, the date of American declared independence from British colonial rule (sidenote: the writer is Dutch and the magazine is published in the U.K.). But this isn’t about Ben Franklin or Thomas Jefferson, and doesn’t even take place in the colonies, but rather signifies the irony of a revolution that resulted in freedom for white Protestant male landowners who relied on the exploitation of African-American slaves to maintain economic autonomy.

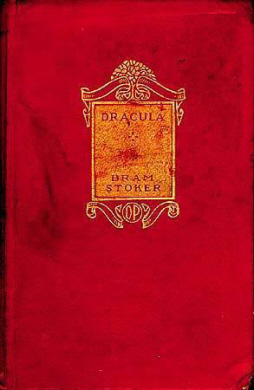

Most literary criticism of Bram Stoker’s Dracula is limited to treating the work as one of the more blatant examples of Victorian sexual repression. A few more adventurous critics are eager to play Freudian detective and speculate what the book reveals about the author’s possible sexual feelings for Sir Henry Irving or his alleged serial infidelity with East End prostitutes.

Most literary criticism of Bram Stoker’s Dracula is limited to treating the work as one of the more blatant examples of Victorian sexual repression. A few more adventurous critics are eager to play Freudian detective and speculate what the book reveals about the author’s possible sexual feelings for Sir Henry Irving or his alleged serial infidelity with East End prostitutes.