Talking Tolkien: The Lay of the Nauglamir

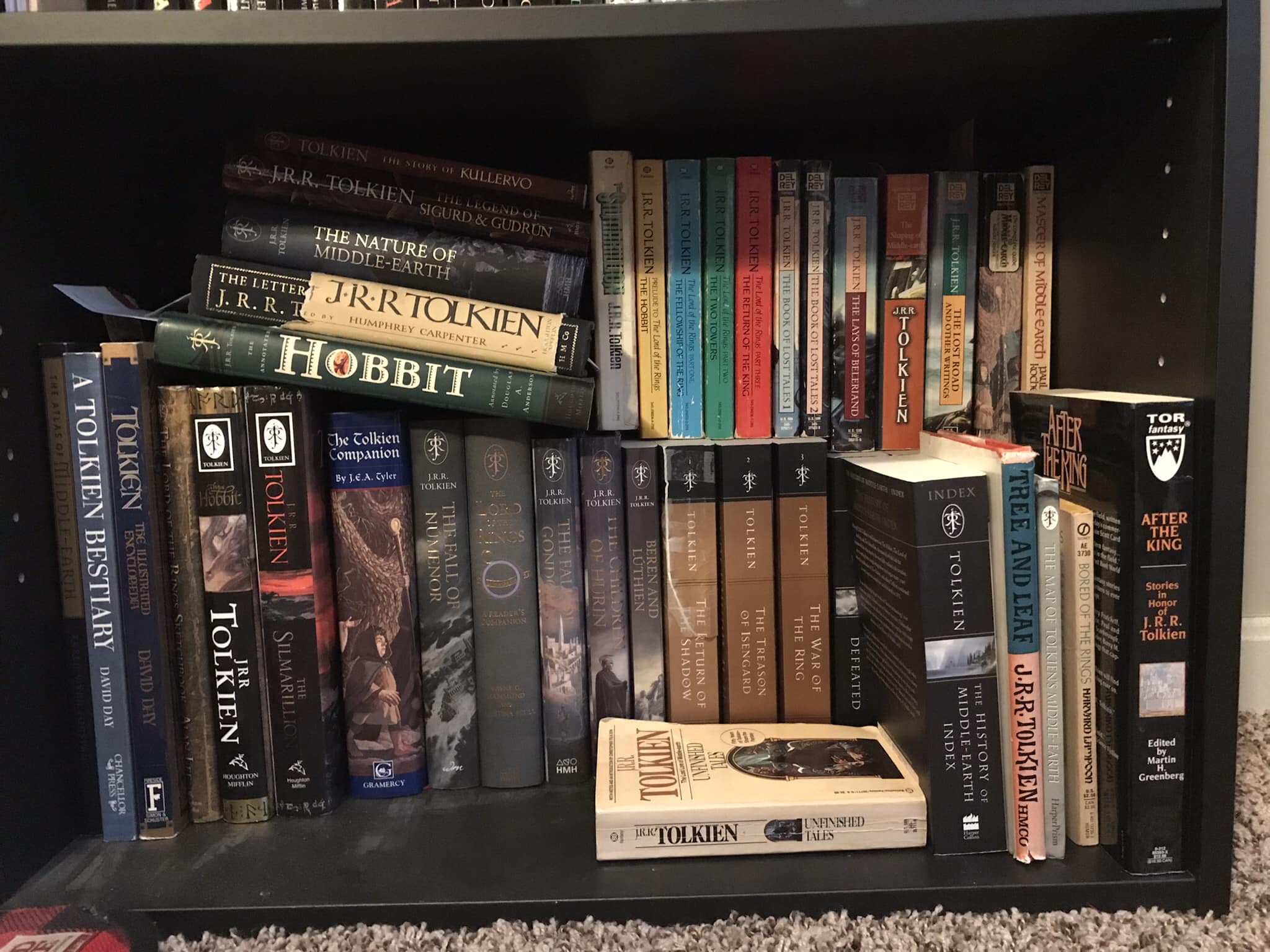

Today in Talking Tolkien, it’s a long-term project I work on every so often. The story of the Nauglamir (The Necklace of the Dwarves) may well be my favorite story in all of The Legendarium. It was the subject of my very first Tolkien essay.

Today in Talking Tolkien, it’s a long-term project I work on every so often. The story of the Nauglamir (The Necklace of the Dwarves) may well be my favorite story in all of The Legendarium. It was the subject of my very first Tolkien essay.

Last year, I read The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun. I really liked that book. I also read part of The Story of Kullervo, though the layout and non-Tolkien commentary didn’t work nearly as well for me (it was not a Christopher Tolkien effort). Tolkien was an expert in this area. The names of the dwarves in The Hobbit came from the old Noridc legends.

If your knowledge of Norse mythology comes from Bulfinch’s – or Marvel comic books – you’re going to find these are VERY different. But I liked reading the old sagas (and no wonder The Silmarillion is so depressing – those old Nordic sagas make Platoon look like a light-hearted romp).

And the Sigurd book got me a bit inspired.

I sketched out the entire history of the Silmaril which was fashioned into Nauglamir, and began creating an epic poem about it (NOT an ‘Epithon,’ for you Nero Wolfe fans out there…). I’m not into metering, so it doesn’t qualify for some definition of verse or form. But it still reads like a poem to me.

It’s 90 lines so far, with a lot more to go. The scope of the Nauglamir Silmaril is truly amazing, and fraught with tragedy. I’ll add more the next time I go into Tolkien mode. It’s the first time I’ve done anything like this (except for a Solar Pons poem I wrote, summarizing “The Unique Dickensians”).

I can put together a haiku on the fly:

Source of joy and woe

Light of Yavanna shining

Pride of the Noldor

This, however, is well outside of my writing zone. But it’s fun.