Talking Tolkien: A Tolkenian Defense of Monsters by James McGlothlin

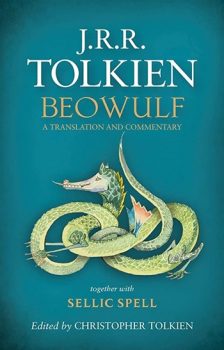

Up this week is another of my fellow Black Gaters. James most recently took us through those classic The Year’s Best Horror Stories anthologies. Back in May, Fletcher Vredenburgh wrote about Tolkien’s Beowulf. While Middle Earth and The Lord of the Rings are Tolkien’s most famous works, Beowulf is a classic of English literature. So, as we start July, James also talks about that epic saga. And if you’ve never actually read Beowulf (or only seen The Thirteenth Warrior), maybe you’ll want to after reading James’ and Fletcher’s essays.

Up this week is another of my fellow Black Gaters. James most recently took us through those classic The Year’s Best Horror Stories anthologies. Back in May, Fletcher Vredenburgh wrote about Tolkien’s Beowulf. While Middle Earth and The Lord of the Rings are Tolkien’s most famous works, Beowulf is a classic of English literature. So, as we start July, James also talks about that epic saga. And if you’ve never actually read Beowulf (or only seen The Thirteenth Warrior), maybe you’ll want to after reading James’ and Fletcher’s essays.

_____________________________________________________________

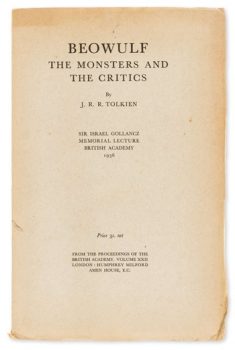

In 1936 J. R. R. Tolkien gave the annual Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture to the British Academy. This talk was later published as the essay “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” in the book The Monsters and Critics. The primary point of this lecture was to offer a defense for studying the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf as, primarily, a poetic work. That proposition may sound obvious; but Tolkien was convinced that it needed to be re-emphasized because the way Beowulf had been largely studied in his day seemed to forget or obscure the point. Tolkien memorably characterizes the situation in what he called the “whole industry” of Beowulf criticism with the following allegory:

A man inherited a field in which was an accumulation of old stone, part of an older hall. Of the old stone some had already been used in building the house in which he actually lived, not far from the old house of his fathers. Of the rest he took some and built a tower. But his friends perceived at once (without troubling to climb the steps) that these stones had formerly belonged to a more ancient building. So they pushed the tower over, with no little labour, in order to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions, or to discover whence the man’s distant forefathers had obtained their building material. Some suspecting a deposit of coal under the soil began to dig for it, and forgot even the stones. They all said: ‘This tower is most interesting.’ And even the man’s own descendants, who might have been expected to consider what he had been about, were heard to murmur: ‘He is such an odd fellow! Imagine his using these old stones just to build a nonsensical tower! Why did not he restore the old house? He had no sense of proportion.’ But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea. (pgs. 7–8, The Monsters and the Critics).

This allegorical depiction captures Tolkien’s frustration that scholarly critics could seemingly neither analyze nor enjoy the tower/poem of Beowulf simply as a poem. Rather, from Tolkien’s perspective, their scholarly endeavors had allegorically “pushed the tower over.” And in doing so, as Tolkien’s metaphor seeks to make plain, they were thus unable to appreciate what the original Beowulf poet had appreciated and still invites all readers to enjoy today: to “look out upon the sea,” the ability to appreciate a vista or perspective that can only be seen when reading the story of Beowulf as the original poet had intended, i.e., as a poem and epic. Why did Tolkien believe this?

It seems that most scholars in Tolkien’s time considered the monsters of Beowulf as a somewhat embarrassing feature of the poem, and quite at odds with its other literary merits. In stark contrast, Tolkien saw the monsters as both necessary and important to the theme of Beowulf. Tolkien notes that many critics in his day believed that Beowulf’s “weakness lies in placing the unimportant things at the centre and the important on the outside” (p. 5). These scholars thought it was perhaps understandable that ancient and medieval simpletons would include monsters within their stories; but what a literary mistake to make them so central to their stories! As Tolkien’s contemporaries saw it, the poetic talent of Beowulf had “all been squandered on an unprofitable theme: as if Milton had recounted the story of Jack and the Beanstalk in noble verse” (p. 13). For these scholars just could not “admit that the monsters are anything but a sad mistake” (p. 16).

But Tolkien, as a lover of the poem as well as a scholar, strongly disagreed for he understood how the monsters of Beowulf intricately served the theme of the poem. And what exactly did Tolkien understand its theme to be? Within the essay Tolkien begins his defense a bit sheepishly noting that “the significance of a myth is not easily to be pinned on paper by analytical reasoning. It is at its best when it is presented by a poet who feels rather than makes explicit what his theme portends” (p. 15). This is well put since poetic and literary expression has long been recognized as capable of expressing truths in powerful ways that more straightforward propositional expression simply cannot. Thus, when someone attempts to explain the content of poetic or literary form, one either is unable to sufficiently do so or seriously risks damaging the content of what was originally communicated. Tolkien recognized this in explaining the theme of Beowulf: “Its defender is thus at a disadvantage: unless he is careful, and speaks in parables, he will kill what he is studying by vivisection, and he will be left with a formal or mechanical allegory, and, what is more, probably with one that will not work” (p. 15).

But Tolkien, as a lover of the poem as well as a scholar, strongly disagreed for he understood how the monsters of Beowulf intricately served the theme of the poem. And what exactly did Tolkien understand its theme to be? Within the essay Tolkien begins his defense a bit sheepishly noting that “the significance of a myth is not easily to be pinned on paper by analytical reasoning. It is at its best when it is presented by a poet who feels rather than makes explicit what his theme portends” (p. 15). This is well put since poetic and literary expression has long been recognized as capable of expressing truths in powerful ways that more straightforward propositional expression simply cannot. Thus, when someone attempts to explain the content of poetic or literary form, one either is unable to sufficiently do so or seriously risks damaging the content of what was originally communicated. Tolkien recognized this in explaining the theme of Beowulf: “Its defender is thus at a disadvantage: unless he is careful, and speaks in parables, he will kill what he is studying by vivisection, and he will be left with a formal or mechanical allegory, and, what is more, probably with one that will not work” (p. 15).

Nevertheless, Tolkien goes on to argue that the Beowulf poet had devoted his work primarily to the theme of the inevitability of Beowulf’s final defeat and death, drawing “the struggle in different proportions, so that we may see man at war with the hostile world, and his inevitable overthrow in Time” (p. 18). There are several explicit Christian references throughout Beowulf, but the pessimistic and pagan Norse idea of fate, or the wyrd, is clearly in the foreground. But as a scholar of ancient Germanic languages, Tolkien believed that Beowulf was not simply a syncretistic stew of Christian and pagan elements, nor a “confusion, a half-hearted or a muddled business, but a fusion that has occurred at a given point of contact between old and new, a product of thought, and deep emotion” (p. 20).

The poet of Beowulf, who was more than likely a Scandinavian Christian monk, knew the older days and traditions of his Norse context. And “one thing he knew clearly: those days were heathen—heathen, noble, and hopeless” (p. 22). And Tolkien recognized the poet as making use of these readily available themes. In the old pagan view, “the monsters had been the foes of the gods . . . and [believed that] within Time the monsters would win” (p. 22). Furthermore, Tolkien noted, the poet knew that “a Christian was (and is) still like his forefathers a mortal hemmed in a hostile world. The monsters remained the enemies of mankind, the infantry of the old war, and became inevitably the enemies of the one God, . . . the eternal Captain of the new” (p. 22). Tolkien spends some significant space in his essay making the case for this point, claiming the author of Beowulf, despite his central use of fictional monsters and pagan ideas, was:

“still concerned primarily with man on earth, rehandling in a new perspective an ancient theme: that man, each man and all men, all their works shall die. A theme no Christian need despise. Yet this theme plainly would not be so treated, but for the nearness of a pagan time. The shadow of its despair, if only as a mood, as an intense emotion of regret, is still there. The worth of defeated valour in this world is deeply felt. As the poet looks back into the past, surveying the history of kings and warriors in the old traditions, he sees that all glory (or as we might say ‘culture’ or ‘civilization’) ends in night. The solution of that tragedy is not treated—it does not arise out of the material. We get in fact a poem from a pregnant moment of poise, looking back into the pit, by a man learned in old tales who was struggling, as it were, to get a general view of them all, perceiving their common tragedy of inevitable ruin, and yet feeling this more poetically because he was himself removed from the direct pressure of its despair. He could from without, but still feel immediately and from within, the old dogma: despair of the event, combined with faith in the value of doomed resistance. He was dealing with the great temporal tragedy, and not yet writing an allegorical homily in verse” (p. 23).

This is also why Tolkien argues earlier in the essay that it is a mistake to understand Beowulf as “the hero of an heroic lay.” Rather, more simply and more straightforwardly the poet presented Beowulf not as a hero but as simply “a man, and that for him and many is sufficient tragedy” (p. 18). Tolkien surmised that beneath what we recognize today as typical monster motifs of the horror genre lay a truer horror and a truer tragedy, which the Christian poet was attempting to communicate within this pagan fictional world: the world of men—this world—is hostile to his happiness and existence, and man is ultimately destined to die. And as Tolkien said above, this is “a theme no Christian need despise” (p. 23). The Christian poet of Beowulf understood that Beowulf’s iron shield that he bore against the monsters of the poem, “was not yet the breastplate of righteousness, nor the shield of faith for the quenching of all the fiery darts of the wicked” (p. 23, Tolkien is alluding here to the “spiritual armor” metaphor of St. Paul in his Letter to the Ephesians 5:13–17).

This is also why Tolkien argues earlier in the essay that it is a mistake to understand Beowulf as “the hero of an heroic lay.” Rather, more simply and more straightforwardly the poet presented Beowulf not as a hero but as simply “a man, and that for him and many is sufficient tragedy” (p. 18). Tolkien surmised that beneath what we recognize today as typical monster motifs of the horror genre lay a truer horror and a truer tragedy, which the Christian poet was attempting to communicate within this pagan fictional world: the world of men—this world—is hostile to his happiness and existence, and man is ultimately destined to die. And as Tolkien said above, this is “a theme no Christian need despise” (p. 23). The Christian poet of Beowulf understood that Beowulf’s iron shield that he bore against the monsters of the poem, “was not yet the breastplate of righteousness, nor the shield of faith for the quenching of all the fiery darts of the wicked” (p. 23, Tolkien is alluding here to the “spiritual armor” metaphor of St. Paul in his Letter to the Ephesians 5:13–17).

Summarizing then, Tolkien understood the theme of Beowulf to be about not only the particular and inevitable death of a warrior in his fictional world, but the general and inevitable death of all mankind in our world. For us, the poem of Beowulf is ancient, “and yet,” notes Tolkien, “its maker was telling of things already old and weighted with regret, and he expended his art in making keen that touch upon the heart which sorrows that are both poignant and remote” (p. 33). Thus, “it is not an irritating accident that the tone of the poem is so high and its theme so low. It is the theme in its deadly seriousness that begets the dignity of tone” (pgs. 18–19). And what better way to communicate that tragic theme in this milieu? This was Tolkien’s main point in the essay: “the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem, which give it its lofty tone and high seriousness” (p. 19). In other words, it is not just the theme of death alone that gives Beowulf its powerful effect, but death by monsters. (Tolkien scholar Verilyn Flieger makes this insightful point in her Splintered Light, p. 17.)

Tolkien concludes the essay with this summary thought: “It is just because the main foes in Beowulf are inhuman that the story is larger and more significant than [other] imaginary poem[s] of a great king’s fall. It glimpses the cosmic and moves with the thought of all men concerning the fate of human life and efforts; it stands amid but above the petty wars of princes, and surpasses the dates and limits of historical periods, however important” (p. 33).

Life is clearly dangerous and fraught with peril. And what better and more impactful way to communicate and represent such truths in a fictional story than with horrific monsters? be mere escapism”

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna – Religious Themes in The Lord of the Rings

Ruth de Jauregui – The Architects of Modern Fantasy, Tolkien and Norton

Fletcher Vredenburgh – Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be – Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

Anglachel – Tolkien’s Evil Magic Sword

David Ian – A Magical Tolkien Celebration

Gabe Dybing – Tolkien and Middle Earth Role Playing (MERP)

James McGlothlin is Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Theology at Bethlehem College & Seminary in Minneapolis, Minnesota. When not reading fantasy, horror or SF for fun, James enjoys studying from a wide range of topics: everything from Old English to ethics, aesthetics, and the theology of Jonathan Edwards. He was also senior lecturer at THE Ohio State University (where I got my Masters Degree).

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, ans XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Well said, Mr. McGlothin, that Prof. Tolkien stitches together the two “halves” of Beowulf with the idea of the world’s unconcern for human happiness, safety, or (especially) life. I always found the second part, fighting the dragon, to be the more compelling, since it neatly establishes that there is only one “retirement” for a hero, no matter how much glory they have accumulated previously. “There were giants in the earth in those days.”

Also, it seems that we are missing the final quoted excerpt for the essay, following “As Tolkien said elsewhere”.

Thank you Eugene for the compliment. I think you’re right about the dragon scene. My personal favorite has always been the Grendel scene. I think the building dread comes through really well there, though the dragon scene is more climactic and symbolic.

Thanks also for pointing out the editing snafu. Mr. Byrne has already fixed it.

“…a mortal hemmed in a hostile world. The monsters remained the enemies of mankind, the infantry of the old war, and became inevitably the enemies of the one God…”. Yes, that resonates with me at a very basic level.

Excellent post. Thank you, Mr. McGlothin.

Thanks for the comment John. Tolkien’s prose, in my opinion, are exquisite in this essay. He expresses himself phenomenally. The quote that most resonates with me is the last line of his tower analogy with *Beowulf*: “But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.”