Talking Tolkien: Religious Themes in Lord of the Rings – Joe Bonadonna

Talking Tolkien is back and it’s Black Gater Joe Bonadonna, musing on religious themes in Lord of the Rings. Since Tolkien set out to compose a mythology for England, and was himself a devout Catholic, it’s no surprise that the topic of religion is certainly relevant to his work. Take it away, Joe…

Talking Tolkien is back and it’s Black Gater Joe Bonadonna, musing on religious themes in Lord of the Rings. Since Tolkien set out to compose a mythology for England, and was himself a devout Catholic, it’s no surprise that the topic of religion is certainly relevant to his work. Take it away, Joe…

First, I want to say that I am most definitely not an expert on Tolkien’s writings and his history of Middle-earth. Certainly, the myriad fans of Tolkien’s work will be familiar with the ideas and concepts that are laid out in this article. Most of what I set down here will be obvious to Tolkien fans and aficionados. I’m not really adding anything new here; this is just an exploration of themes I’ve always found interesting, and whenever I find myself in a discussion with other fans of Lord of the Rings, I always find myself bringing up the topic of religious ideas in the books, and the fact that there are no churches or other holy places. (It can be argued that all Middle-earth — every forest, every river, every mountain, every pasture is sacred, I suppose.)

Why aren’t there any priests, nuns or priestesses in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings? Do Hobbits go to church? Do Elves worship at a temple? Do dwarves belong to a mosque or synagogue? Do they all pray to Eru/Ilúvatar? And where do they go to pray? A special house of worship or is anywhere they pray become a sacred place?

Those are some of the questions I inevitably ask.

Since first reading The Hobbit in 1968, I’ve read it only one other time; I’ve read Lord of the Rings three times, but have only read The Silmarillion once. When The Children of Hurin was first published, I read that. I am pretty unfamiliar with the professor’s other works, however. My sources used in research for this article are: Ruth S. Noel’s The Mythology of Middle-Earth, Robert Foster’s The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth, Paul H. Kocher’s Master of Middle-Earth, William Ready’s Understanding Tolkien, Humphrey Carpenter’s Tolkien: The Complete Biography, as well as The Hobbit, The Return of the King, and The Silmarillion.

Please note: although the titles of Kocher’s, Noel’s and Foster’s books use a capital E for “earth,” I will use Middle-earth as Tolkien himself did in his stories. All that being said, I just wanted to clear the air so you good folks who are reading this will know that I am by far no Tolkien expert. As we all know, Tolkien was not only a devout Catholic and an English professor, he was also a philologist and a scholar. He was well-versed in the Celtic mythology and the Icelandic Sagas, and he combined these influences with his Christianity to create the world of Middle-earth.

Please note: although the titles of Kocher’s, Noel’s and Foster’s books use a capital E for “earth,” I will use Middle-earth as Tolkien himself did in his stories. All that being said, I just wanted to clear the air so you good folks who are reading this will know that I am by far no Tolkien expert. As we all know, Tolkien was not only a devout Catholic and an English professor, he was also a philologist and a scholar. He was well-versed in the Celtic mythology and the Icelandic Sagas, and he combined these influences with his Christianity to create the world of Middle-earth.

This article first began as an essay many years ago, based on questions I had regarding the fact that there are no churches, no religious organizations represented in b and Lord of the Rings. I only began thinking about this after reading other fantasy novels published under Ballantine Books’ Adult Fantasy series, and then discovering Fritz Leiber’s The Swords of Lankhmar, L. Sprague de Camp’s The Tritonian Ring, and Robert E. Howard’s Cimmerian warrior in the old Lancer edition of Conan the Adventurer, back in the late 1960s. Fantasy novels — whether Heroic, High or Epic — as well as Sword & Sorcery, mostly featured different religions and faiths, churches and temples, high priests and priestesses, and often a pantheon of gods and goddesses.

After reading The Silmarillion and then rereading Lord of the Rings, it came to me that perhaps, in the elder days, when life in Middle-earth was so close to the source, to the beginning of all things, when “angelic” beings and “infernal” entities shared Middle-earth with Men, there was no need for organized religion, no need for churches and priests and weekly “services.” Mankind had not yet strayed from “the beginning” and had no need of religious institutions. I’m sure many of you out there know more than I do, and can answer my questions and even enlighten me. While there may be an absence of hierarchical religion in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, there is a strong yet subtle undercurrent of theological elements to be found.

The Creation

In the beginning there was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar. He first created the Ainur, the Holy Ones, who were the children of his thoughts. They were with him before all else was made. After Eru created the Ainur with the Flame Imperishable of his luminous spirit, he gathered them together and revealed part of his mind to them. He declared the Three Great Themes, the Ainulindale, which was an expression of his divine order. Guided by Eru, the Ainur began to sing, and their music went out into the Void and thereafter was no longer a void.

What Tolkien has done here is to give us the Supreme Being, Eru Ilúvatar. The Holy Ainur are depicted as angels, fashioned for the glory of Eru and to fulfill his divine purpose. Through music the Universe was then formed, according to the Three Themes: Creation, Heaven and Earth; and Life. (This all adds weight to the many ancient songs sprinkled throughout the pages of The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s other works.) The first two themes were  made when the Ainur sang with voices that were “like unto harps and lutes, pipes and trumpets, and viols and organs, and like unto countless choirs singing with words.” Out of the Void, as a result of the Ainur’s music, Ea (the Universe) was conceived, and the concept of Creation came into being. Comprised of Arda (Earth) and Ilmenal (Heaven), Creation was then animated by the Secret Fire and was bound by the principles of Matter, Space and Time. Then the world was given form, and the Vision that was in Ilúvatar’s mind was revealed in all its splendor and glory. But it fell solely upon Ilúvatar to fashion the last of the Three Themes: Life.

made when the Ainur sang with voices that were “like unto harps and lutes, pipes and trumpets, and viols and organs, and like unto countless choirs singing with words.” Out of the Void, as a result of the Ainur’s music, Ea (the Universe) was conceived, and the concept of Creation came into being. Comprised of Arda (Earth) and Ilmenal (Heaven), Creation was then animated by the Secret Fire and was bound by the principles of Matter, Space and Time. Then the world was given form, and the Vision that was in Ilúvatar’s mind was revealed in all its splendor and glory. But it fell solely upon Ilúvatar to fashion the last of the Three Themes: Life.

The Blessed Realm

The Blessed Realm consisted of Eressea (The Lonely Isle), and the land mass known as Valinor, the Land of the Valar. Eressea lay just off the coast of Valinor, so both areas were given the name Eldamar — Elvenhome. Also called Aman the Blessed, the Undying Lands, little is known of this mystic realm, save that it lies in the uttermost West. It’s kept isolated from the mortal world by a barrier of darkness that separates Middle-earth and the immortal lands. While Tolkien’s description is at best somewhat nebulous, the Blessed Realm can be interpreted as the Afterlife, Purgatory or an “otherworld,” if not as Heaven itself. In a way, the Blessed Realm can be compared to the land of Emain, the Celtic Faerie, where lived the Elves. According to Tolkien, the Elves, who were immortal, traveled at ease between Middle-earth and the Undying Lands. Mortals, however, were rarely accepted in Aman the Blessed; not only was this the home of immortals, it was also the home of the dead, the spirits of Elves. Being immortal, the Elves did not die of old age or sickness, though they could be slain in battle. This concept was borrowed from Celtic mythology, wherein the Elves and the Old Gods dwelled together with the dead.

The Undying Lands can also be identified with the realm of Avalon, from the tales of King Arthur. Sorely wounded and near death, Arthur was taken to Avalon for healing and to dwell until a time when England would once again have need of her once and future king. At the close of The Return of the King Tolkien echoed this mystical sequence from Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur in the scene at the Gray Havens, when Frodo and Bilbo depart Middle-earth and sail to the Blessed Realm. Their ship passes on into the West until one rainy night when Frodo smells a sweetness in the air and hears the sound of singing. Then the curtain of rain rolled back “and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise” — a passage of dialog Peter Jackson had Gandalf say to Pippin during the Siege of Gondor, in the cinematic version of The Return of the King. It is quite evident here that Frodo and Bilbo have passed from life into death, for this is symbolized by the rain and the white color of the shores. Neither Frodo, Bilbo, Gandalf and the company of Elves with whom they sailed were ever again seen in Middle-earth. They had been accepted in the Undying Lands of the Blessed Realm.

The Valar

The Valar were the fourteen greatest of the Ainur who chose to enter Ea to fulfill the Vision of Ilúvatar. Although beings of pure spirit, the Valar usually assumed physical forms of great beauty. They were angelic powers, guardians of the world, and were physically and spiritually remote from the human world. In Middle-earth the fates of both the mortals and immortals were determined by the Valar, though they were under the direction of Ilúvatar. Their task, upon entering Creation, was to prepare the physical substance of the earth, to make it ready for the grand awakening of the Children of Ilúvatar: Elves and Men. (Dwarves are not counted among the Children of Ilúvatar. Their creator was Mahal, known as Aulë the Smith of the Valar, who was concerned with rock, metal, the nature of substances, and works of craft. Aulë created the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves, from whom all other Dwarves are descended, deep beneath an unknown mountain somewhere in Middle-earth. Aulë was a Vala and one of the Aratar, who were the Holy Ones of Arda; eight of them there were, and they were the greatest of the Valar.)

The Valar were the fourteen greatest of the Ainur who chose to enter Ea to fulfill the Vision of Ilúvatar. Although beings of pure spirit, the Valar usually assumed physical forms of great beauty. They were angelic powers, guardians of the world, and were physically and spiritually remote from the human world. In Middle-earth the fates of both the mortals and immortals were determined by the Valar, though they were under the direction of Ilúvatar. Their task, upon entering Creation, was to prepare the physical substance of the earth, to make it ready for the grand awakening of the Children of Ilúvatar: Elves and Men. (Dwarves are not counted among the Children of Ilúvatar. Their creator was Mahal, known as Aulë the Smith of the Valar, who was concerned with rock, metal, the nature of substances, and works of craft. Aulë created the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves, from whom all other Dwarves are descended, deep beneath an unknown mountain somewhere in Middle-earth. Aulë was a Vala and one of the Aratar, who were the Holy Ones of Arda; eight of them there were, and they were the greatest of the Valar.)

Now, although the Valar knew the Third Theme of the Ainulindale, which dealt with the creation of Life, the Valar did not participate in this part of the Vision; this was Ilúvatar’s demesne, which only he alone could bring forth. Here we see Tolkien’s Catholicism at work, using The Bible and other religious tomes for inspiration.

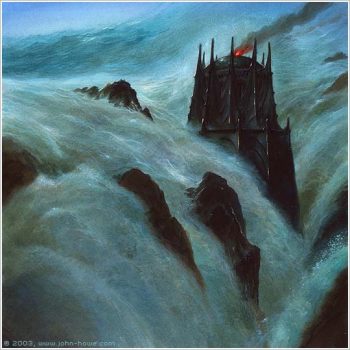

Of all the Valar who entered Ea, the most influential in the history of Middle-earth was Melkor, whose name means “He who arises in might.” Like Lucifer, Melkor was filled with pride and was of a jealous disposition. Once favored by Ilúvatar, Melkor fell from grace and chose to live in exile in Middle-earth, which he soon began to corrupt and turn to his own evil purposes. Desiring to dominate all life and the will of others, Melkor claimed the earth as his own. His betrayal of the Blessed Realm closely parallels Lucifer’s attempt to conspire against God and usurp the Throne of Heaven. Melkor’s sin, one of the recurring sins in Tolkien’s works, was covetousness. He desired and then stole the Silmarilli: three crystal jewels that held the light of the Two Trees of Valinor. As he fled the Blessed Realm, he poisoned the Trees so only he could view their splendor and radiance, since no one save he now possessed any portion of the Two Trees. This theft brought about the first alliance of Elves and Men, and was the beginning of the history of Middle-earth. Melkor’s act of betrayal echoes the fall of Lucifer and the rise of Satan.

Just as Lucifer was cast out from the Light of God and was deprived of his name, so was Melkor. The Noldor Elves, afraid to utter his true name, called him Morgoth, the Great Enemy. He was known by other names, as well: Foe of the Valar; the Master of Lies; Lord of Darkness. All these are further comparisons to Satan. In his vanity and arrogance, Morgoth again blasphemed by proclaiming himself King of the World.

Parallels To Christ

This should come as no surprise to anyone who has read Lord of the Rings or seen the cinematic version of the trilogy: the most obvious of all of Tolkien’s religious themes were the allusions he drew to Jesus Christ. Gandalf the Wizard is depicted as a mystical figure, an old man wise and learned in ancient lore. He was one of the Istari, the lesser Valar, who were sent to Middle-earth under the direction of the Valar, to unite and counsel the Free Peoples in their struggle against the Powers of Darkness. Gandalf was immortal and he lived in the Blessed Realm before entering Middle-earth. Towards the conclusion of The Return of the King he returns to the Undying Lands with Bilbo, Frodo and a company of Elves, to dwell for all time.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf confronts the Balrog in Moria, a creature wielding a fiery whip, a creature “like a great shadow, in the middle of which was a dark form, of man-shape maybe, yet greater, and a power and terror seemed to be in it and to go before it.” In order to save the other members of his company Gandalf does battle with the Balrog upon the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, destroying the bridge by smiting it with his staff. As we all know, the bridge breaks, and so does Gandalf’s staff. The stone upon which the Balrog stands also cracks, and the creature plunges into a bottomless gulf. “But even as it fell it swung its whip, and the thongs leashed and curled about the wizard’s knees, dragging him to the brink.” Then Gandalf tells his friends to flee as he is pulled down into the abyss, which can be interpreted as the pit of death, and the Balrog as Death itself. Even though Gandalf is immortal, like the Elves, he can be slain in battle. But he defeats Death and passes from the mortal lands of Middle-earth and is not again seen in his usual form. His self-sacrifice, the giving of his life to save his friends mirrors Christ’s willingness to be Crucified and to die so that Man could inherit the Kingdom of Heaven.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf confronts the Balrog in Moria, a creature wielding a fiery whip, a creature “like a great shadow, in the middle of which was a dark form, of man-shape maybe, yet greater, and a power and terror seemed to be in it and to go before it.” In order to save the other members of his company Gandalf does battle with the Balrog upon the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, destroying the bridge by smiting it with his staff. As we all know, the bridge breaks, and so does Gandalf’s staff. The stone upon which the Balrog stands also cracks, and the creature plunges into a bottomless gulf. “But even as it fell it swung its whip, and the thongs leashed and curled about the wizard’s knees, dragging him to the brink.” Then Gandalf tells his friends to flee as he is pulled down into the abyss, which can be interpreted as the pit of death, and the Balrog as Death itself. Even though Gandalf is immortal, like the Elves, he can be slain in battle. But he defeats Death and passes from the mortal lands of Middle-earth and is not again seen in his usual form. His self-sacrifice, the giving of his life to save his friends mirrors Christ’s willingness to be Crucified and to die so that Man could inherit the Kingdom of Heaven.

In The Two Towers, Aragorn, the rightful heir to the Throne of Gondor, accompanied by Gimli the Dwarf and Legolas the Elf, encounter a bent old man cloaked all in gray. The old man then reveals himself, shedding his cloak, and it is Gandalf, dressed now all in white. He says to his friends, “I have passed through fire and deep water, since we parted.” Gandalf did, indeed, die. When he says that “None of you has any weapon that could hurt me,” he is quite literally telling us that he has transcended mortality and death. He has been returned to Middle-earth by the grace of the Valar, who sent him back for a time to finish the task he was sent there to accomplish ages ago. Once he was known as Gandalf the Gray, his color symbolizing old age. Now he is Gandalf the White, for he has died, only to be resurrected for a time. He has supplanted Saruman the White, who succumbed to the lure of the One Ring and made a bargain with Sauron — literally a bargain with the Devil.

Gandalf’s return to Middle-earth was only temporary, for when completed his mission he must return to the Undying Lands of the Blessed Realm. Gandalf implied this when he said, “Naked I was sent back, for a time, until my task was done.” So was the Messiah resurrected and sent back into the world for a brief time, to finish his task and counsel his disciples; Christ’s resurrection was proof that if you had faith in God, you would attain eternal life. When Christ’s task was finished, he ascended to Heaven. When Gandalf’s task upon Middle-earth was accomplished, he returned again to the Blessed Realm. Another similarity between Gandalf and Christ occurs when Gimli the Dwarf, having mistaken the wizard at first for the enemy and nearly attacking him with his axe, loudly proclaims, “Since Gandalf’s head is now sacred, let us find one that is right to cleave!” The key word here is sacred.

Thus, the parallels to Christ are quite evident, sometimes stated forthrightly, at other times only alluded to in subtle passages of song, prose or poetry. Tolkien fills the pages of Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion with myth and legend, songs and historical accounts. Though his works sometimes tend to stand back from any theology and religious worship, there is still plenty of natural religion in his body of work. There may be an absence of temples and idols, priests and sacred rituals in his stories, but there is nonetheless a deep-rooted element of basic religion to be found in Tolkien’s books. Tolkien himself established a pervasive but unobtrusive theology for Middle-earth. The gods were alive and responsive to the needs of both mortals and immortals in those elder ages, taking an active part in their fate. Elves and Men, Hobbits and Dwarves — all lived secure in their belief, and even though it colored their actions, was seldom spoken of.

And so, my questions remain: Why aren’t there any priests, nuns or priestesses in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings? Do Hobbits go to church? Do Elves worship at a temple? Do dwarves belong to a mosque or synagogue? Do they all pray to Eru/Ilúvatar? And where do they go to pray? A special house of worship or is anywhere they pray become a sacred place?

Perhaps they did pray, in private, and not with some religious congregation. Perhaps they had no need for organized religion because they were so close to the Origins of Life. Perhaps only in the later ages of Man was there a need to form various religions, and to build churches, temples, mosques, and synagogues.

In my view, Tolkien gave us a Bible for Middle-earth: The Silmarillion.

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna

Joe Bonadonna is the author of the heroic fantasies Mad Shadows—Book One: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser (winner of the 2017 Golden Book Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy); Mad Shadows — Book Two: The Order of the Serpent; Mad Shadows—Book Three: The Heroes of Echo Gate; the space opera Three Against The Stars and its sequel, the sword and planet space adventure, The MechMen of Canis-9; and the sword & sorcery pirate novel, Waters of Darkness, in collaboration with David C. Smith. With co-writer Erika M Szabo, he penned Three Ghosts in a Black Pumpkin (winner of the 2017 Golden Books Judge’s Choice Award for Children’s Fantasy), and its sequel, The Power of the Sapphire Wand. He also has stories appearing in: Azieran: Artifacts and Relics; Savage Realms Monthly (March 2022); Griots 2: Sisters of the Spear; Heroika I: Dragon Eaters; Poets in Hell; Doctors in Hell; Pirates in Hell; Lovers in Hell; Mystics in Hell; Liars in Hell; Sinbad: The New Voyages, Volume 4; Unbreakable Ink; Stand Together — A Collection of Poems and Short Stories for Ukraine; the shared-world anthology Sha’Daa: Toys, in collaboration with author Shebat Legion; and with David C. Smith for the shared-universe anthology, The Lost Empire of Sol. In addition to his fiction, Joe has written numerous articles, book reviews and author interviews for Black Gate online magazine.

Visit Joe’s Amazon Author’s page!

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI and XXI.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

The climax of The Lord of the Rings strikes me as a very Catholic resolution, in that Frodo succeeds by a combination of “faith and good works” in destroying the One Ring. His faith in Gollum is the key to his final success, as his good works alone only bring him to the brink, but not put him over the edge (so to speak). His last “sin” in falling into temptation is redeemed by the grace of his faith.

I guess one reason why religion doesn’t feature in LOTR is that religion – specifically Christianity – is a reality in Middle-Earth. It has its own equivalent of heaven and hell, demons and Lucifer, with the elves being pretty much indistinguishable from angels. Plus I’d see Rivendell, Lothlorien etc as all being iterations of Eden.

Exactly! You summed up my whole article in 3 sentences!

My bad, Joe – I should have been paying more attention….

In terms of priests etc. If God is propping up your local bar most Saturday nights and willing (within reason) to answer your questions and maybe even help you out – if he’s in the mood – then religion as an institution is largely redundant.

Also, while temples and priesthoods do figure prominently in stories by Howard, Leiber, CAS, etc., the priesthoods are often corrupt and/or the temples just places full of stuff for the heroes to take (possibly after defeating some kind of eldritch horror).

Were there fantasy stories prior to Katherine Kurtz’ Deryni where there was religion but it was just part of the fabric of the world?

Good point, Joe. Most sword and sorcery stories I’ve read contain a certain religious theme, the gods more often than not either in minor roles or just used as “world building” background – and the gods are either mad, evil or very distant. If I remember correctly – and it’s been a long time since I’ve read them – David Edding’s The Belgariad and The Malloreon series, the only ones I read, had some sort of gods involved. Perhaps in a “deus ex machina” role. I loved Leiber’s concept: the gods OF Lankhmar and the gods IN Lankhmar.

I’m waaaay late to the conversation here, but it is a good point that in most of the classic pulp S&S, the priesthoods are usually shams and the gods are usually monsters of some kind. Does anyone know of any sympathetic S&S priests? Instead of a wandering barbarian swordsman, it would be a wandering missionary (or whatever).

Thank you, Bob! Lovely presentation, I must say.

The lembas bread the elves eat and give to the hobbits has a sort of eucharistic quality. It’s not necessarily enjoyable to eat, essentially just being bread, but it’s tremendously nourishing and bolsters their spirits as much as their bodies.

Wow – I never thought of it in terms of the eucharist! Well played!

I had the sort of same question as you Joe: where is religion in this supposedly religious work? I then recently read Ralph C. Wood’s *The Gospel According to Tolkien* and he pointed out a whole bunch of religious or religiously-themed ideas and parallels between Christianity and Tolkien’s works that I had never noticed before. Very convincing book.

Everyone may read here

https://efanzines.com/PortableStorage/PortableStorage-06.pdf

my article “Contemplated but Not Resolved: Opening Up Lear and The Lord of the Rings,” in William Breiding’s acclaimed fanzine Portable Storage. The key to understanding religion and The Lord of the Rings is the now-unfamiliar, once-everyday method of typology. You can read The Lord of the Rings the way you would “read” cathedral sculpture or frescoes. This sounds drab and scholarly, I suppose, but I aimed at a lively and readable style. Give my piece a read and see if I succeeded.

Interesting piece but lots of little mistakes in retelling the lore, like saying that Istari are lesser Valar. No, they are Maiar. You also seem to not remember or understand that the Blessed Realm was not hidden until after the Fall of Numenor (which you’ve read The Silmarillion, so you do know about it). Also, Men did not appear until long after the Noldor returned to Middle-earth, but you make it seem like they were allies from the start.

And you speak of Valinor as a land of the dead, but never mention the Gift of Men, how men don’t go to Mandos when they die but somewhere beyond the world. This includes Frodo, Bilbo, and Sam (and perhaps Gimli, the fate of Dwarves is not known.) after their time in Valinor, which is only a short time of rest and healing, not a permanent heaven for them.

Lastly, you ask repeatedly about temples and yet don’t mention the one written about in detail by Tolkien, the temple to Morgoth ereceted on Numenor before its downfall thanks to Sauron. I really thought this would bear mentioning since it is the only one in the Legendarium and is unequivocally bad.

You ask about prayer and don’t mention at all the way people on Numenor before the corruption went up to the hallowed spot on the Meneltarma to pray, which you could call a sort of church or temple too.

As I said, you said you’ve read the Silmarillion, so you should be familiar with these things, and surely they were mentioned in your sources too?

It just seems like you ignored two clear answers to your own questions. Also, if you’d looked in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien you’d have found that he directly addressed your questions and that the answer is that they didn’t have religion because with the Elves still around there is memory of the Valar and Valinor and so faith is not needed, that would come later when only stories remain. There is no need for faith and religion when there is no question as to the answer.

Also, you completely missed Melkor’s actions during the Music, which I found odd.

Good article Tom, many thanks for writing it. As an English church pastor I often remind the congregation the church building is merely a convenience. It keeps us dry when it’s raining, it used to keep us warm in winter (until all the energy prices went through the roof) and it helps people to have a meeting place. Early Christians meet in each others houses or by riversides, nothing wrong with a woodland grove either, when the weather is good.

I think that it is worth remarking upon that both Tolkien and Lewis hid their Christian themes behind a dazzling curtain of paganism.

I wonder if, in Tolkien’s case, it was more a matter of convenience, he already had a lot plates spinning and adding any kind of organized religion would have just been too much. Also, the closest thing that I recall to an organized religion is what Melkor sets up in Numenor– with the temple and the sacrifices and the fire and the foom and the killing.

I also wonder if Tolkien, knowing the pagan epics and the thin-veneer of Christianity over some pagan epics, AND the history of the saints, determined that the first two were where the real literary gold was to be mined.