Retro Review: Two F&SFs from Robert P. Mills’ Editorship

|

|

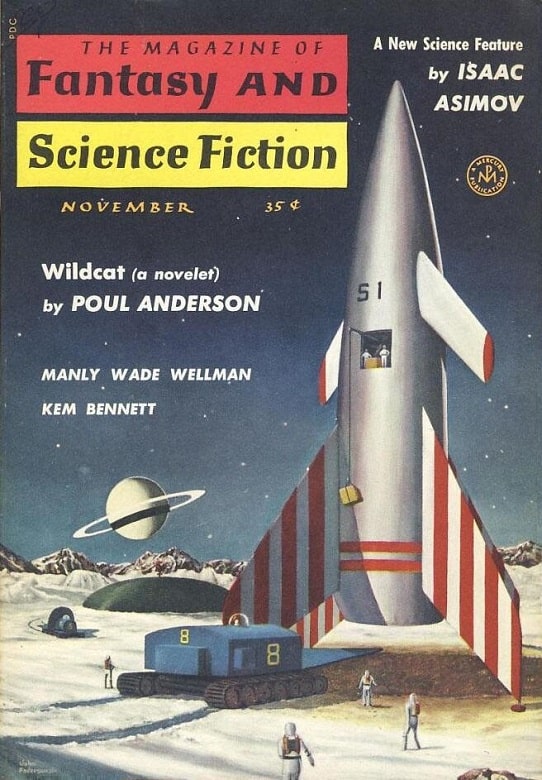

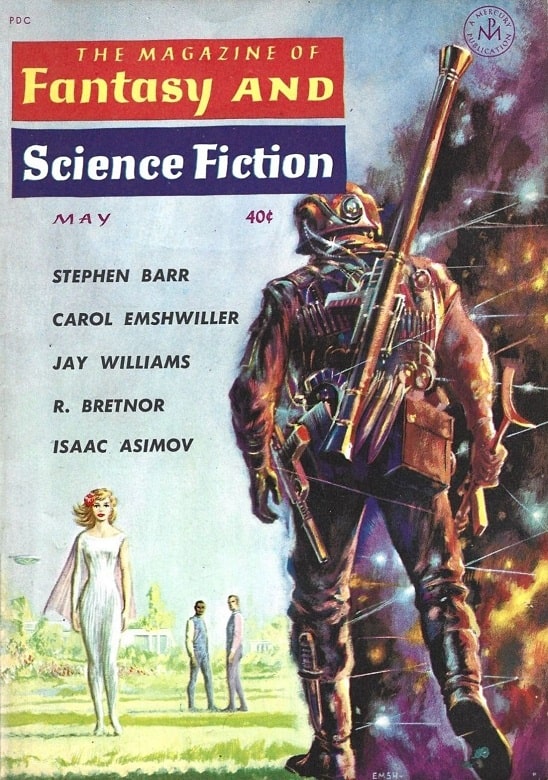

The November 1958 and May 1961 issues of The Magazine of

Fantasy & Science Fiction. Covers by John Pederson and Ed Emshwiller

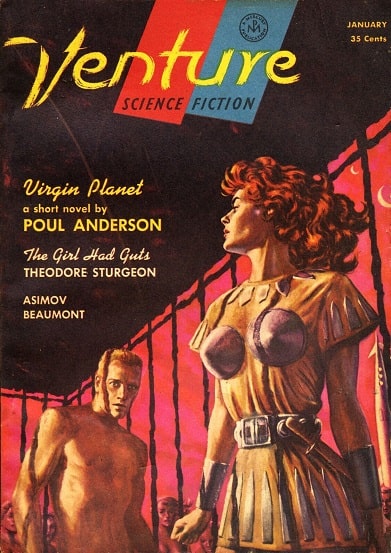

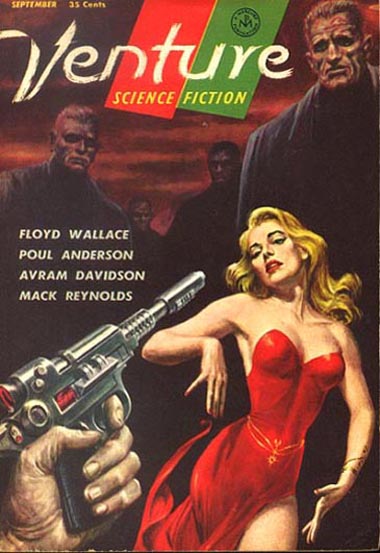

I’ve recently looked at a few issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction from the early to mid-50s, when Anthony Boucher (at first in collaboration with J. Francis McComas) was the editor. Boucher left that post with the August 1958 issue, and Robert P. Mills took over. (Mills had been the editor of F&SF’s sister magazine Venture for its ten-issue stint running bimonthly from January 1957 through July 1958.) He edited F&SF until the March 1962 issue.

These two issues, then, neatly mark a period early in his term, and one in the last year of his term. So it seems like a good idea to consider them together. (If truth be told, though, I bought these for another reason — they feature two of the very best stories from the first phase of Carol Emshwiller’s career.)

Let’s look quickly at the TOCs of the two issues.

[Click the images to venture to larger versions.]

|

|

|

Venture magazines edited by Robert P. Mills: January, September, and November 1957. Covers by Ed Emshwiller

November 1958

Stories

“A Different Purpose,” by Kem Bennett (6,400 words)

“Bewitched,” by Michael Fessier (4,900 words)

“Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot: IX,” by Reginald Bretnor [as by Grendel Briarton] (200 words)

“Critical Angle,” by A. Bertram Chandler (2,500 words)

“Or the Grasses Grow,” by Avram Davidson (3,000 words)

“Wildcat,” by Poul Anderson (12,000 words)

“Beans,” by Jack Williamson (300 words)

“Mr. Milton’s Gift,”by Robert Arthur (5,000 words)

“Pelt,” by Carol Emshwiller (3,600 words)

“For Analysis,” by P. Schuyler Miller (500 words)

“Nine Yards of Other Cloth,” by Manly Wade Wellman (6,300 words)

Features:

“Air Space Violated,” by P. M. Hubbard (poem)

“Dust of Ages,” by Isaac Asimov

“Recommended Reading,” by Anthony Boucher

“For the Voyagers,” by Starr Nelson (poem)

May 1961

Stories:

“Adapted,” by Carol Emshwiller (3,000 words)

“The Teeth of Despair,” by Avram Davidson and Sidney Klein (5,000 words)

“All the Tea in China,” by Reginald Bretnor [as by R. Bretnor] (2,800 words)

“Somebody to Play With,” by Jay Williams (3,700 words)

“Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot: XXXIX,” by Reginald Bretnor [as by Grendel Briarton] (200 words)

“Poltergeist,” by C. D. Heriot (4,500 words)

“Mr. Medley’s Time Pill,” by Stephen Barr (5,500 words)

“The Country Boy,” by G. C. Edmondson (5,800 words)

“The Flower,” by Mildred Posselt (74 words)

“The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Ross,” by Henry Slesar (3,800 words)

“Final Muster,” by Rick Rubin (8,400 words)

Features:

“Heaven on Earth,” by Isaac Asimov

“Books,” by Alfred Bester

November 1958

Now for a closer look at the November 1958 issue. (I should note that for an issue this early in an editor’s term, there’s a good chance some of the stories were selected by the predecessor, Boucher in this case.)

The two poems are “Air Space Violated” and “For the Voyagers.” P. M. Hubbard published three poems in F&SF, and several short stories. This one was a reprint from Punch. Starr Nelson published two poems in the magazine, this one original (though the other was reprinted from Saturday Review.)

There are three very brief vignettes: Williamson’s “Beans,” Miller’s “For Analysis,” and the Feghoot. None are very good. All depend on puns. “Beans” concerns a potential alien invasion. “For Analysis” is about an attempt to understand the significance of a crashed Soviet spaceship. The Feghoot involves a landing on a smog-filled alien planet and the search for food. I have to say — and this applies to the Feghoot in the May 1961 issue as well — that while I enjoyed many of these when I read them decades ago, these two are simply tiresome.

|

|

|

Methuselah’s Children by Robert Heinlein (Signet, January 1960), The Year’s Greatest Science-Fiction

and Fantasy: Third Annual Volume, edited by Judith Merril (Dell, July 1958), Star Born by Andre Norton

(Ace Double, 1958). Covers by Paul Lehr, Richard Powers, and Ed Emshwiller

Anthony Boucher’s Recommended Reading column is as ever interesting. He covers Heinlein’s Methusaleh’s Children, Merril’s third Year’s Best anthology, and “juveniles” by Edward Eager and Andre Norton, including an Ace Double reprint of her Star Born, backed with the H. Beam Piper/John J. McGuire short novel A Planet for Texans. He is largely approving of all, while noting that he didn’t consider 1957 a very good year for short fiction. There is also a page-long list of very brief capsules — I was amused that two of them (back to back) were Lest We Forget Thee, Earth, by “Calvin M. Knox”; and Starhaven, by “Ivar Jorgenson” — Boucher surely knew that both “Knox” and “Jorgenson” were Robert Silverberg but carefully made no mention of that.

(Side note — I have just read Elizabeth Gaskell’s great 1855 novel North and South, which features a minor character named Boucher. I “read” the audio version, and Boucher’s name was pronounced “BOUT-Churr,” just as William Anthony Parker White intended his pseudonym to be pronounced, even though I and many others reflexively think of it as “Boo-SHAY.”)

Kem Bennett’s “A Different Purpose,” like Miller’s “For Analysis” and for that matter Anderson’s “Wildcat,” is a Cold War story, though it doesn’t really focus on the superpower conflict. Perhaps to call it a Space Race story would be more accurate. (And there is another Space Race story in this issue as well, Chandler’s “Critical Angle.”) Yourko Andropov (presumably no relation to the future Communist Party General Secretary!) has been chosen to be the first man in orbit. The story covers a bit of his preparation, and then his time in orbit. The real point of the story is the psychological stresses on him — he has to cut his mission short — and then the unsatisfying reaction of the authorities and doctors when he returns. It’s a well-executed psychological story, even if the motivating crisis is a bit unconvincing.

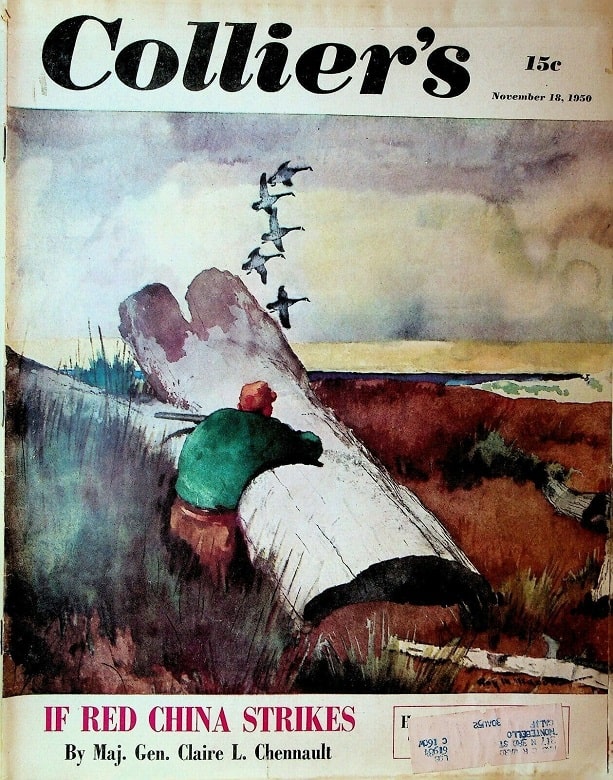

Collier’s Magazine, November 18, 1950, containing “Bewitched” by Michael Fessier

One of the key features of F&SF throughout its history (though it’s been less common in recent decades) has been reprints of stories with fantastical elements that first appeared in so-called “mainstream” publications. Robert P. Mills signaled right away that he would continue this, “Bewitched,” by Michael Fessier, is an example — it first appeared in the November 1950 Collier’s. (Fessier (1905-1988) published several SF or Fantasy stories (three of them reprinted in F&SF and another anthologized by Murray Leinster) and a couple of fantastical novels. He’s better known as a screenwriter, with credits including the Fred Astaire/Rita Hayworth musical You’ll Never Get Rich and even an episode of Gilligan’s Island.) “Bewitched” is a fun romantic story about a shy girl who is mad that her nasty cousin will lure away the man she’s interested in. She meets a woman who claims to be a centuries-old witch, and the woman bewitches her to be able to turn into a cat — and the catlike qualities both intrigue her beau, and give her the gumption to put her cousin in her place.

The next two pieces are a sort of pair. First, “The Dust of Ages” is Isaac Asimov’s very first science article for F&SF. The column continued for some 30 years, until Asimov died (with some appearing until February 1992, for a total of 400 by my count, though an essay called “Essay 400 — A Way of Thinking,” by Janet Asimov and Isaac Asimov, appeared in 1994. Most of these articles were later collected in books — 374 in all, I believe. (The book series ended before the last several appeared in F&SF, and a few more essays were never collected.)

“The Dust of Ages” (given as “Dust of Ages” in the TOC) is much briefer than most of Asimov’s F&SF articles, only some 1,200 words long. (Todd Mason notes that Asimov had begun a series of science columns for Venture in 1958, with a smaller word count. When Venture was discontinued, Mills had Asimov continue the column in F&SF, and soon bumped up the word count.) It discusses the then common notion that the Moon might be covered with a deep layer of very fine dust. I don’t think this idea fell wholly out of fashion until the Moon landing in 1969, and it was central to Arthur C. Clarke’s fine 1961 novel A Fall of Moondust. But Asimov never collected this essay, either because he already doubted the science, or because it was much shorter than his standard F&SF pieces.

A. Bertram Chandler’s “Critical Angle,” just following “The Dust of Ages,” was placed there on purpose, because it also treats the idea of a big layer of Moon dust, though in a very silly fashion. An American spaceship is hurriedly sent to the Moon, after the Russians get there first (in an unmanned ship) and paint a big red star in Copernicus. The American ship is manned, and lands in Copernicus… and then, as with Clarke’s novel, sinks deeply into the dust. The crew members must dig their way out… with unexpected (and as I suggested, very silly) consequences.

“Or the Grasses Grow” is one of Avram Davidson’s bitterest — and most powerful — stories. It tells of the last gasp of an Indian tribe trying to keep its land, while the government works to dispossess them, despite the treaty saying the land is theirs “as long as the sun rises or the grasses grow.” The characters and their anger are excellently depicted, and the story comes to a truly effective and dark conclusion.

|

|

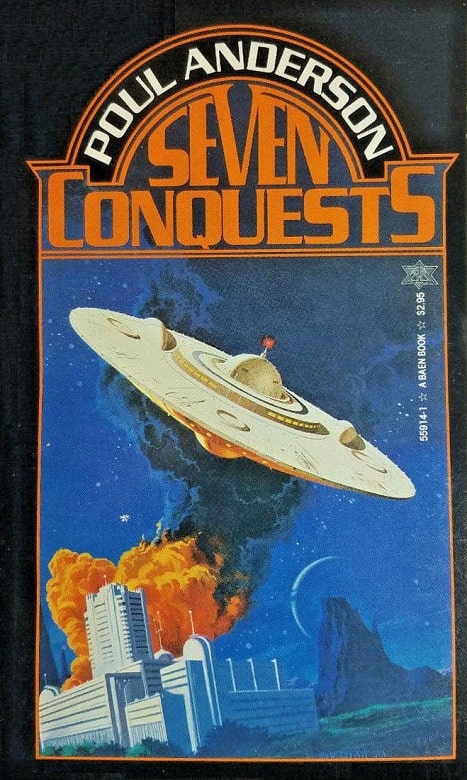

Seven Conquests by Poul Anderson (Baen, October 1984). Cover by Vincent DiFate

I am sure I read Poul Anderson’s “Wildcat” before, probably in his collection Seven Conquests, but I didn’t remember it at all. It’s a time travel story, set in the Jurassic. Herries is the head of a large group of workers in the Jurassic… maintaining a camp that is aimed at drilling for oil to send back to the present day. (Anderson acknowledges that most people think that oil formed essentially from (as he puts it) “rotting dinosaurs,” but he cites a theory of Fred Hoyle’s that oil was formed before the Earth formed.) The project is to help the US keep up with the USSR in what seems clearly a less and less stable Cold War. His foil is Symonds, the comptroller (but really a spy for the government.) The job is terribly dangerous, and it seems that people are killed by dinosaurs all the time, but Symonds won’t authorize more powerful weapons.

Things come to a head when a young man Herries had taken a liking to is killed by a Tyrannosaurus Rex (yes, I know — this is a weird error by Anderson, as T. Rex was a Cretaceous dinosaur.) A top secret delivery from the future is coming, instead of the weapons Herries wants… and he decides to disobey the rules and see what’s in the delivery… and, well, I won’t spoil it. It’s a significant surprise, and while I don’t think the story works on the whole, the ultimate conclusion is at least interesting.

All the handwaving and contrivance to set things up is too much, however. A pretty minor part of the Anderson oeuvre. (One other thing I noticed was Anderson carefully, and not at all overtly, describing Herries’ team as a very diverse group (except as to gender.) He briefly mentions the “chocolate” complexion of one man, another has a Native American name and another a Polish name, Herries’ unfortunate young friend is obviously Jewish though that’s never stated. This is thin diversity gruel, I’m sure, but it’s clearly an earnest effort to say that this is not an all-white milieu — and, really, that has some meaning when the final surprise is sprung.)

Robert Arthur’s “Mr. Milton’s Gift” is another reprint — it was first published in Blue Book for July 1953. Arthur (1909-1969) is probably best known as the “ghost editor” behind a number of the Alfred Hitchock Presents series of anthologies. He wrote a fair amount of fiction as well, including a series of “bar stories” (like Wodehouse’s Mr. Mulliner stories, or Dunsany’s Jorkens stories, or Clarke’s Tales from the White Hart) narrated by a certain Murchison Morks. In this entry Morks tells the story of Horace Milton, an accountant, who has forgotten a gift for his wife, and wanders into one of those mysterious Olde Shoppes … and comes out with two gifts — the gift of making money, and the gift of poetry… of course, these don’t work out quite as well as one might hope! It’s amusing in just the way you expect from this sort of story.

Carol Emshwiller published her first story in 1954, and was never less than interesting, but first got wide notice with “Hunting Machine” in 1957, the first of three selections in three years for Judith Merril’s Best of the Year anthologies. “Pelt” was the second of these, “Day at the Beach” the third. All those stories are still highly regarded, but “Pelt” is the best remembered, and it’s quite powerful. It’s told from the point of view of a dog, a hunting dog, on an alien planet, devotedly serving her master’s desire for a pelt. But there is another temptation… this world is a lovely world, and there are voices telling her so… The ending is wrenching, dark, and tangled with meaning… slavery, love, betrayal, murder… Quite a story.

I read a couple of Manly Wade Wellman’s later Silver John stories decades ago, and they were fine, but didn’t make a strong impression on me. In my recent reading of back issues of F&SF, I’ve seen a couple of his earlier stories about John — and they’ve been really good. “Nine Yards of Other Cloth” is very fine work. John comes to Hosea’s Hollow, where long ago Hosea Palmer had done battle with a monster named Kalu, and had never returned — but neither had Kalu. And here he finds a lovely young woman, Evadare, who, he learns, is here because it may be the only place another sort of monster, Shull Colbert, who has a magic violin and wants to possess Evadare, might be afraid to go.

Inevitably, the story leads to a confrontation between John and Shull… and a slightly unexpected final resolution.

May 1961

This issue opens with another Carol Emshwiller story, “Adapted,” and this was to be her last story for five years. (She had very young children, and presumably she stopped writing to care for them.) I said that “Pelt” is the best remembered early Emshwiller story, but I think this is my favorite. It’s a woman talking to her child, who is different. And she was different too, in her youth, though she never knew her father, who was also “different.” We hear how she learned to try to hide her strangeness, and of her marriage, and her constant attempts to be like other women, and then a hope that perhaps her real people have found her… it’s sad, and dimly hopeful (at least for the child) and quite original. A feminist parable, sure, and a comment, perhaps, on the ’50s, but different. The full Carol Emshwiller voice is here.

“The Teeth of Despair” is a slight but enjoyable piece. It’s Sidney Klein’s only credit — I suspected he may have suggested the basic idea to Avram Davidson. I asked Seth Davis, Avram’s godson and literary executor, and he told me that Klein (who lived in Yonkers, Davidson’s hometown) was a dear friend of Avram’s since childhood, and in fact Sidney and his wife Nancy were godparents to Ethan Davidson, Avram’s son with Grania Davis. Seth says that Sidney, an engineer, read Avram’s “Help! I am Dr. Morris Goldpepper” and had the idea at the heart of this story, and as Seth puts it (presumably as related to him by his mother Grania) Sidney and Avram discussed how the story would work, giggling all the time.

In “The Teeth of Despair,” Thomas Grew is a poorly paid professor, and one night while watching a quiz show on TV he blurts out the answer to a question — and Herman Grackl, the none-too-intelligent contestant, repeats his words. Soon they realize that Grew can communicate with Grackl via a dental plate installed in the latter’s mouth. They decide to split the TV show winnings… but, of course, something is bound to go wrong! Amusing. Not surprising, given that Sidney Klein had the idea for the dental plate while reading one of these stories, it’s peripherally related to the two other Davidson stories about dentistry, “Help! I am Dr. Morris Goldpepper” and “Dr. Morris Goldpepper Returns,” for the dentist who installed the plate in Herman Grackl is none other than Morris Goldpepper.

R. Bretnor’s “All the Tea in China” is a pretty sound Deal with the Devil tale, about a rich man who covets another man’s girl. He ends up trapping the Devil… And he’s very careful to make an airtight deal. But — well, the Devil usually wins! Slight again, but well done.

|

|

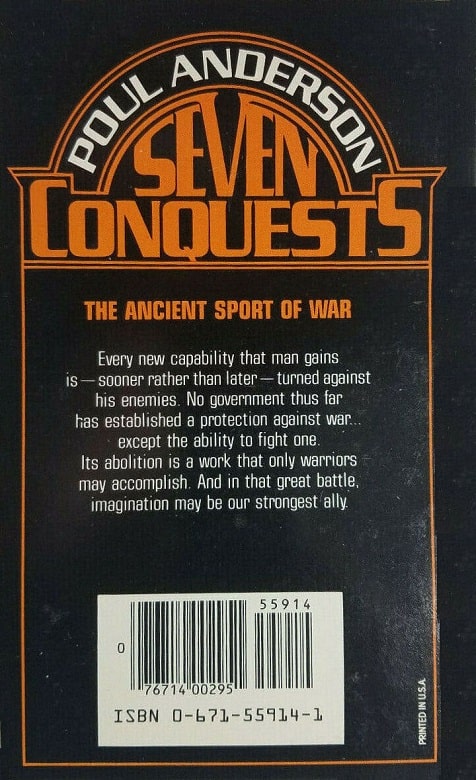

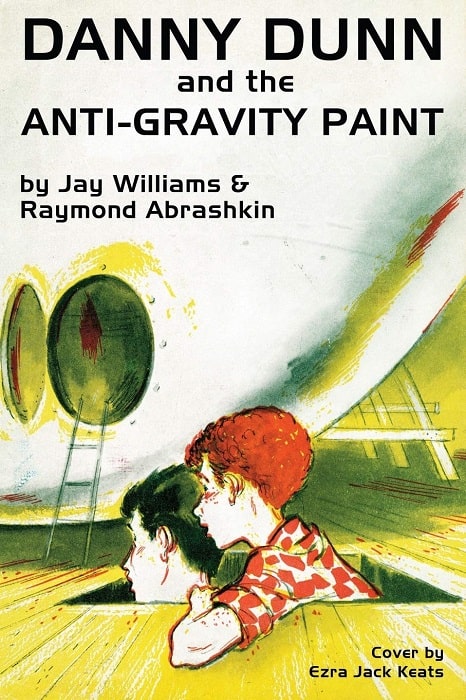

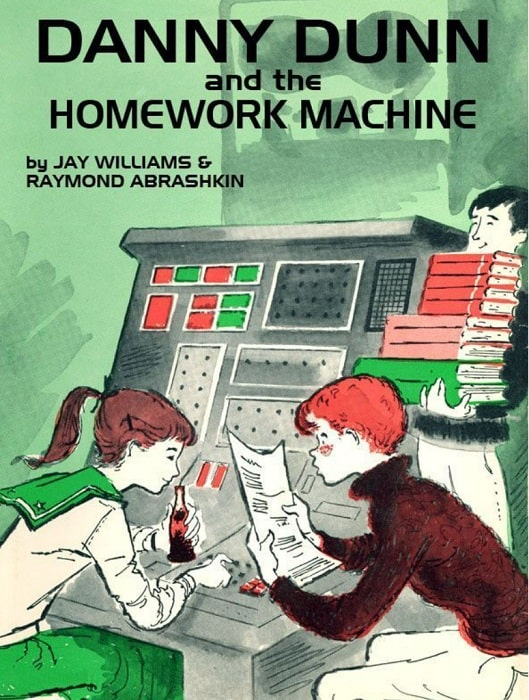

Danny Dunn and the Anti-Gravity Paint, and Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine

by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin (Whittlesey House, 1956 and 1958). Covers by Ezra Jack Keats

Jay Williams (1914-1978) is best known to many readers of a certain age (like me) as the co-author of the Danny Dunn books, but he also published a couple of dozen stories in the SF magazines. “Somebody to Play With” is set on another planet, settled by a smallish group of humans after atomic wars made Earth uninhabitable. (It seems plausible the planet is Mars, but it is not specified.) The people live in domes, as the outside is dangerous, and only marginally survivable. But Nicky is a bored kid, and he sneaks out one day, and encounters a strange birdlike creature. The ending is dark, and pointed, and well set up. It’s a pretty good story.

This issue’s reprint from a literary source is C. D. Heriot’s “Poltergeist,” which was first published in the classic British mainstream original anthology series Winter’s Tales (the third volume, from 1957.) Heriot doesn’t seem much remembered — apparently he was known for writing supernatural stories. He also had a curious position — Examiner of Plays in the office of the UK’s Lord Chamberlain. Apparently into at least the 1950s, plays had to be approved by the Lord Chamberlain in order to be licensed for performance. “Poltergeist” is a minor piece about a troubled little girl who develops the ability to move things by her mind — and is eventually shocked into the realization that what she’s up to is dangerous. I thought it went along well enough until the too pat ending.

“Mr. Medley’s Time Pill,” by Stephen Barr, is a clever little time travel story, about a chemist in England in 1937. Besides his job as a traditional English “chemist” (what Americans call a pharmacist) he dabbles in experimental chemistry. He also has a shrewish wife with a deadbeat brother who lives with them… So, he invents a time travel pill, and uses himself as a subject. He realizes quickly that jumping forward in a time just a day or two leads to complications when he runs into himself. He also learns that winning a lot of money by betting on the right horse doesn’t work if your bookie is dishonest. But — maybe he can use his time pill to solve that problem, not to mention the problem of the shrewish wife and her brother etc. Does his plan work? Well, read the story.

(By the way, the ISFDB claims that this Stephen Barr is the same as the prominent physicist Stephen Barr, son of SF writer Donald Barr and brother of former Attorney General William Barr. I find that improbable, given that the physicist was born in 1953 and the writer Stephen Barr published his first story in 1957. UNLESS — maybe he used his physics knowledge to build a time machine, read a bunch of old F&SFs, and went back in time to submit those stories…! Anyway, I’ve submitted an edit to the ISFDB, so perhaps it will be fixed soon.)

|

|

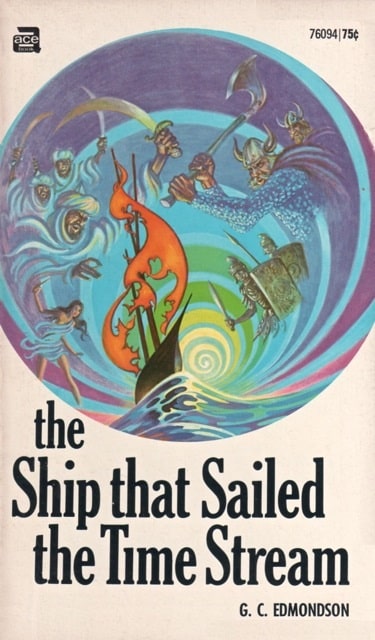

The Ship That Sailed the Time Steam and To Sail the Century Sea by G. C. Edmondson

(Ace 1970, and July 1981). Covers by Frank Kelly Freas and Paul Alexander

G. C. Edmondson (1922-1995) was born in Mexico, say some sources (others say Washington state.) He wrote SF as G. C. Edmondson, and also Westerns under various pseudonyms. (According to the ISFDB, his full name was José Mario Garry Ordoñez Edmondson y Cotton.) He is best remembered these days for his first novel, The Ship That Sailed the Time Stream, and its sequel To Sail the Century Sea.

“The Country Boy” is one of a series of stories called the Mad Friend stories, written for F&SF between 1957 and 1981. All but the last were collected in Stranger Than You Think. “The Country Boy” is pretty wild… it begins in a sidewalk cafe in France, a hangout for Catalan revolutionaries, with the narrator drinking a crummy French beer and thinking about the wunderkind about to be elected President and then likely to precipitate (it seems) nuclear war, when his mad friend shows up, and then a Byzantine, and his Mexican wife and soon enough there’s discussion of time travel to Neanderthal times, missing wing nuts, and whether possession of a soul is a prerequisite for political office. (“Probably not” concedes the mad friend, and surely we realize that by now, to our sorrow.) Madcap stuff, snappily written, clever as all get out — really quite fun. I have not read Edmondson before now, perhaps I should try more.

Mildred Posselt was 11 years old when she wrote “The Flower” (her only credit in the ISFDB.) It is very short at 74 words, and the ISFDB calls it a poem, though I think it qualifies as a story, a brief horror piece about a weird flower. (There is a Mildred Posselt, age 74, living in Franklin, MA, apparently. That would suggest she was born in 1949 — entirely consistent with writing a story at age 11 that appeared in F&SF in 1961.)

Henry Slesar’s “The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Ross” is a dark moral fable about the title character, who, after breaking his leg, discovers the ability to make curious “trades” — in this case, his broken leg for his hospital roommate’s pneumonia. Once out of hospital, he wonders how he can use this ability to get Leah, the girl he loves, beginning by trading his hair for a bald bartender’s money. He keeps trading, hoping to be worthy of Leah, only to learn that riches aren’t what she wants — she wants a man with a heart, with compassion for others. And — well, let the story tell how that works out. It’s fine work.

Rick Rubin (not to be confused with the brilliant record producer who was born two years after this story was published) has three credits in the ISFDB — two F&SF stories in 1961, and one in Playboy in 1962. I don’t know any more about him. But “Final Muster” is pretty impressive. It’s set in a future in which war — indeed, violence in general — has been conquered. There is one remaining military unit, as, long in the past, it was decided that only the people who want to be soldiers should fight the wars, and they are put in cold sleep between wars. It’s been 300 years since the last one, after a 75-year interval before that. Seems like the instinct to fight has been removed, but now the regiment has been awakened again.

They learn that they have been wakened now because it’s been decided there is no need for them as soldiers any more — now they can be free to live the civilian life in a peaceful utopia. But they learn that they just aren’t made for that kind of life — and, moreover, that these future civilians really are different, really cannot be goaded into conflict. I found the conclusion unexpectedly moving (even if I couldn’t quite buy the basic premise.) I was reminded of Damon Knight’s great story “The Country of the Kind.” This story hasn’t been forgotten — it’s been collected a few times in anthologies of Military SF — but it’s not well-known, and I think it’s worth a look.

Now to the features. Asimov’s science column had hit its stride by this time. “Heaven on Earth” talks about number systems (decimal versus duodecimal versus sexagesimal) on the way to discussing how to, in essence, measure the sky. (Angular measure, basically.) And he presents a pretty neat way of thinking about the apparent size of things in the sky (as seen from Earth) — how big a circle would they make if drawn on the Earth’s surface (as perceived from its center)? So, for example, the Moon would be a circle 36 miles in diameter, Venus just over a nautical mile, Jupiter just under a statute mile, Pluto about 17 feet, Betelgeuse less than 5 feet, and so on. (This essay was reprinted in Asimov’s first collection of F&SF essays, Fact and Fancy, in 1962, and in a couple of his later books.)

|

|

|

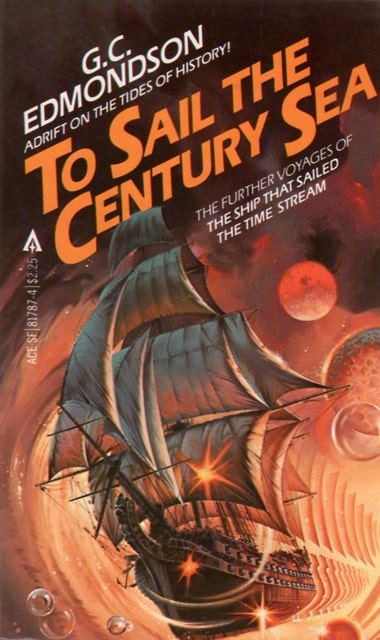

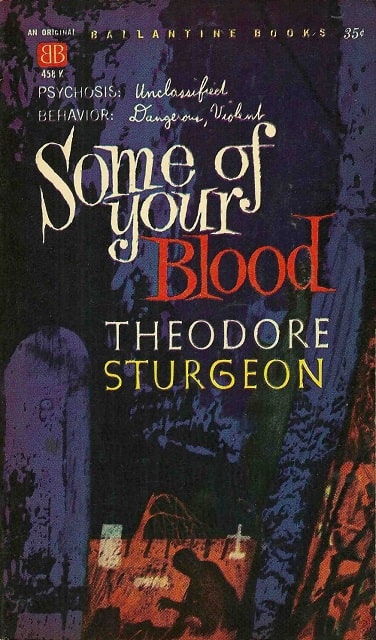

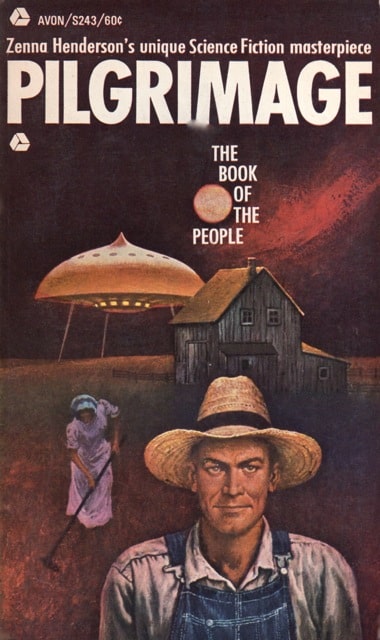

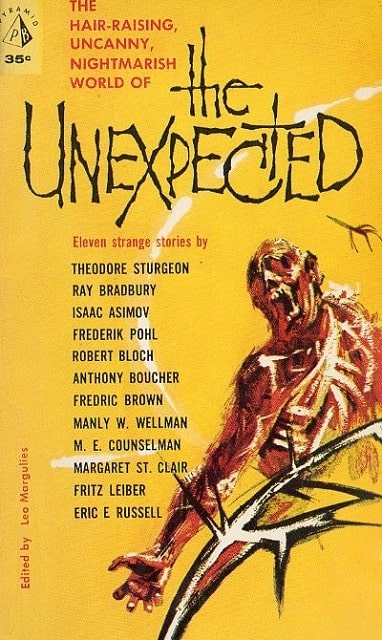

Some of Your Blood by Theodore Sturgeon (Ballantine Books, 1961), Pilgrimage: The Book of the People

by Zenna Henderson (Avon, January 1967), and The Unexpected, edited by Leo Margulies (Pyramid Books,

February 1961). Covers by unknown, Hector Garrido, and John Schoenherr

Alfred Bester wrote the book column this issue (he handled the column for about two years between 1960 and 1962.) He reviews The Fifth Galaxy Reader; Theodore Sturgeon’s Some of Your Blood; Zenna Henderson’s first collection of People stories, Pilgrimage; a non-fiction book by Ben Bova, The Milky Way Galaxy; Poul Anderson’s Twilight World, a fixup of a couple of his first published stories (including his very first, “Tomorrow’s Children”); and The Unexpected, an anthology edited by Leo Margulies.

His highest praise is reserved for Sturgeon’s novel. In the Galaxy Reader review he notes that H. L. Gold is on medical leave from Galaxy — and of course, he was soon permanently replaced by Frederik Pohl. (It is widely assumed that Pohl had already been doing the bulk of the editing work for a couple of years anyway.)

In sum, this seems a decent portrayal of the Mills years: a solid job of continuing the F&SF tradition, complete with a certain tolerance for whimsy, a habit of reprinting stories from outside the genre, a tropism towards short stories and short novelets (though there were exceptions, and occasional serials.) There are three great or near-great stories in these two issues: the two Emshwiller pieces and the Davidson solo story, and several more quite solid pieces, and only a couple of true clunkers (these mostly very short.)

Rich Horton’s last article for us was an obituary for Amazing editor Joseph Wrzos. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Rich, this is a terrific write-up of the two F&SF issues. I didn’t start reading the magazine until around 1978, so I love seeing how much hidden gold is in these older issues. And I loved seeing Jay Williams appeared was represented in it. I read the Danny Dunn books in elementary school many many moons ago and helped develop an interest in written science fiction. And for the record, I’ve always pronounced Boucher as “butcher.” Now I have to look these issues up and do some reading!

Thanks, Mark! I started reading F&SF in 1974 myself. And, yes, I read the Danny Dunn books when I was 10 or so … definitely they were one of my gateways to SF.

Interesting – in the 50+ years since I first learned of “Anthony Boucher”, I never considered that there might be any pronunciation other than “BOUT-churr”.

I have most of the issues of F&SF from the late ‘50s to the early ‘90s, but November 1958 is among the three dozen or so I’m still missing from the period. It seems like a good one to look out for. I’m particularly fond of Wellman’s “John” tales.

I don’t think I ever read a Feghoot that didn’t induce a groan from me – I’ve never been a fan of puns.