Vintage Treasures: The Calling of Bara by Sheila Sullivan

|

|

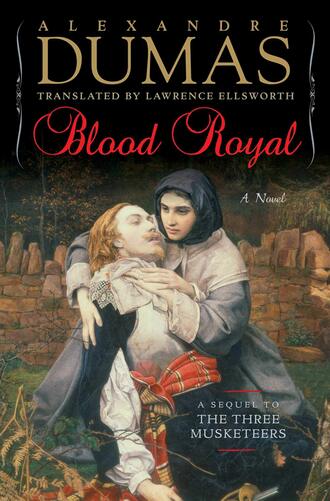

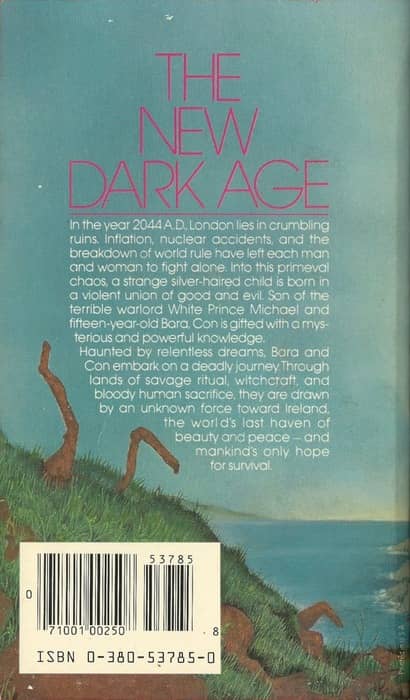

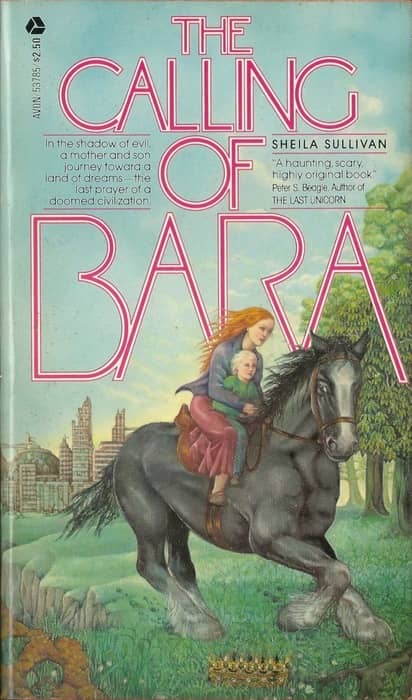

The Calling of Bara (Avon, 1981, cover uncredited)

I like to use my Vintage Treasures columns to highlight overlooked classics of SF and fantasy, or books that mean something special to me. But every once in a while I’ll stumble on a complete mystery, a book I’ve never previously come across in over four decades of collecting. Are these titles worth showcasing? Of course they are! You even have to ask?

Which brings us to The Calling of Bara, a 1981 Avon paperback I found in a collection I bought on eBay over the summer. Never seen it before, and never heard of the author, Sheila Sullivan, either. But it’s clearly dressed up as a mainstream fantasy — and it even has an enthusiastic blurb on the cover by the great Peter Beagle (“”A haunting, scary, highly original book.”) Plus, it’s got a post apocalyptic, ruined-Earth vibe, and that’s a plus. That was enough to send me on the hunt for online mentions, and eventually I found this 40-year-old Kirkus Review in the faded memory banks of an old Univac machine at the U. of I:

When Con, the child Bara bears in 2044 — after all 20th century western civilization had crumbled away — is five years old, Bara hears voices within her demanding she bring Con to Ireland. They are pursued by Con’s father, the savage White Michael, travel through wild lands and tribes, until, after being joined by Bara’s man Tam, they are welcomed in Ireland by the ruling class of telepaths which had called them. Con, with his unique powers, will one day head this elite who are debating whether or not to restore 20th century civilization, while the evil principle, White Michael, waits in the wings. Atmospheric and moderately involving if you haven’t been there before.

Atmospheric and involving… evil principle… crumbling ruins. What the hell, my needs are simple. I’ll try it.