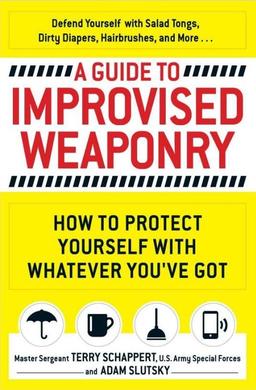

Books for Writers: A Guide to Improvised Weaponry

There are a lot of how-to manuals for writers out there–books about world building, books about grammar, books about finding markets, books about almost every aspect of the writing life. Sadly, there’s no book telling writers how to defend themselves if an axe murderer invades their home office.

There are a lot of how-to manuals for writers out there–books about world building, books about grammar, books about finding markets, books about almost every aspect of the writing life. Sadly, there’s no book telling writers how to defend themselves if an axe murderer invades their home office.

Until now.

A Guide to Improvised Weaponry is the perfect self-defense manual for any writer. It tells you just how to defend yourself when ISIS terrorists decided your work in progress makes you a candidate for their next YouTube video. It’s written by Terry Schappert, a Green Beret and Master sergeant in the U.S. Army Special Forces. This guy knows how to kill you with a pencil. It’s co-written by Adam Slutsky, a professional writer who probably had to explain to Terry that a disappointing advance, low royalties, and non-compete clauses are not valid reasons for killing an acquisitions editor with a pencil.

Each chapter focuses on a common object that you probably have in your home. I was especially interested in objects that are in my home office, ready to be picked up the moment one of my many anonymous online haters kicks in my door.

First, my coffee cup, strategically located to the left of my computer, ready to protect me and mine. Schappert makes the obvious suggestions, like flinging my hot Ethiopian brew into my attacker’s face or using it as a knuckle duster, with the caveat that there’s a good chance of hurting your hand with that second method. He also explains how you can use it to catch the tip of your attacker’s knife and deflect the blow.