Edgar Rice Burroughs Dictated His Work — So I Tried It

Over his nearly forty-year career, Edgar Rice Burroughs put into use every writing method available to him. In a letter to the Thomas A. Edison Company regarding their Ediphone machine, which ERB purchased in 1922, he wrote: “I have written longhand and had my work copied by a typist; I have typed my manuscripts personally; I have dictated them to a secretary; and I have used the Ediphone.” (He didn’t mention in the letter that he also used the Dictaphone, Edison’s competitor.) Although Burroughs would shift his writing methods over the decade and sometimes returned to the trusty typewriter — even letting a ghostly force take over the typing duties in the prologue to Beyond the Farthest Star — wax cylinder dictation machines became his preferred tool. In his daily log of writing progress, he’d describe his workload in terms of how many wax cylinders he’d gone through that day. “May 24 Dictated 5 cyl. today — something over 4000 words.”

Over his nearly forty-year career, Edgar Rice Burroughs put into use every writing method available to him. In a letter to the Thomas A. Edison Company regarding their Ediphone machine, which ERB purchased in 1922, he wrote: “I have written longhand and had my work copied by a typist; I have typed my manuscripts personally; I have dictated them to a secretary; and I have used the Ediphone.” (He didn’t mention in the letter that he also used the Dictaphone, Edison’s competitor.) Although Burroughs would shift his writing methods over the decade and sometimes returned to the trusty typewriter — even letting a ghostly force take over the typing duties in the prologue to Beyond the Farthest Star — wax cylinder dictation machines became his preferred tool. In his daily log of writing progress, he’d describe his workload in terms of how many wax cylinders he’d gone through that day. “May 24 Dictated 5 cyl. today — something over 4000 words.”

In the letter to the Edison Company, Burroughs listed the reasons he preferred to work using dictation machines: “Voice writing makes fewer demands upon the energy … it eliminates the eyestrain … the greatest advantage lies in the speed. I can easily double my output.” He kept his Ediphone (or Dictaphone) near his bedside “to record those fleeting inspirations that would otherwise be lost forever.”

At the time, dictation machines were primarily used for businesses. In order to make the most out of one, a writer had to have a stenographer to transcribe the wax cylinder recordings, so dictation machines weren’t much use to pulp fiction writers. But Edgar Rice Burroughs was both a writer and a business. He was wealthy enough to have an office staff, including a secretary whose job was to type up the manuscript from ERB’s cylinder output. The secretary would also do the job of shaving each wax cylinder — this required its own machine — so it could be reused.

It’s often struck me that writers get more respect in other countries than they do in North America (I’m thinking specifically Europe here, since that’s the limit of my experience). When I told my (Spanish) mother as a child that I was going to be a writer when I grew up, she asked why was I wasting time talking to her, why wasn’t I getting started?

It’s often struck me that writers get more respect in other countries than they do in North America (I’m thinking specifically Europe here, since that’s the limit of my experience). When I told my (Spanish) mother as a child that I was going to be a writer when I grew up, she asked why was I wasting time talking to her, why wasn’t I getting started?

I wonder if there’s still a distinction to be made between holidays and vacations?* Back before “holy day” became “holiday” was there even such a thing as a vacation? Or were holy days really enforced vacations, in the sense that for some of them at least no work was allowed? Would that make the Sabbath a vacation as well as a holy day? Hmmm.

I wonder if there’s still a distinction to be made between holidays and vacations?* Back before “holy day” became “holiday” was there even such a thing as a vacation? Or were holy days really enforced vacations, in the sense that for some of them at least no work was allowed? Would that make the Sabbath a vacation as well as a holy day? Hmmm.

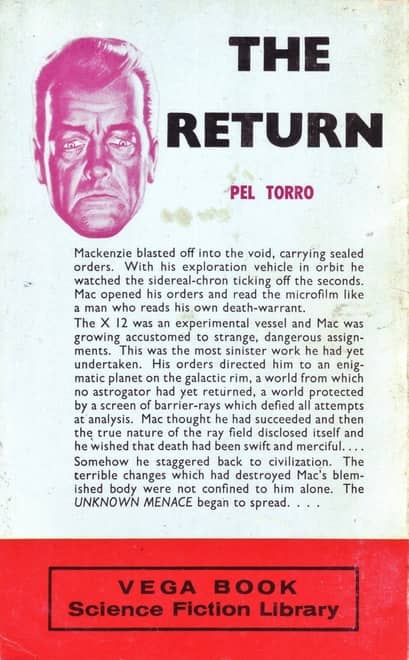

There was a time when genre in fiction writing wasn’t quite the crowded mishmash of categories and sub-categories, and sub-sub-categories that we’re faced with now, which in any case double in number with the use of the prefix “YA.” There are so many that sometimes it gets difficult to decide which one you’re writing – or reading for that matter.

There was a time when genre in fiction writing wasn’t quite the crowded mishmash of categories and sub-categories, and sub-sub-categories that we’re faced with now, which in any case double in number with the use of the prefix “YA.” There are so many that sometimes it gets difficult to decide which one you’re writing – or reading for that matter.