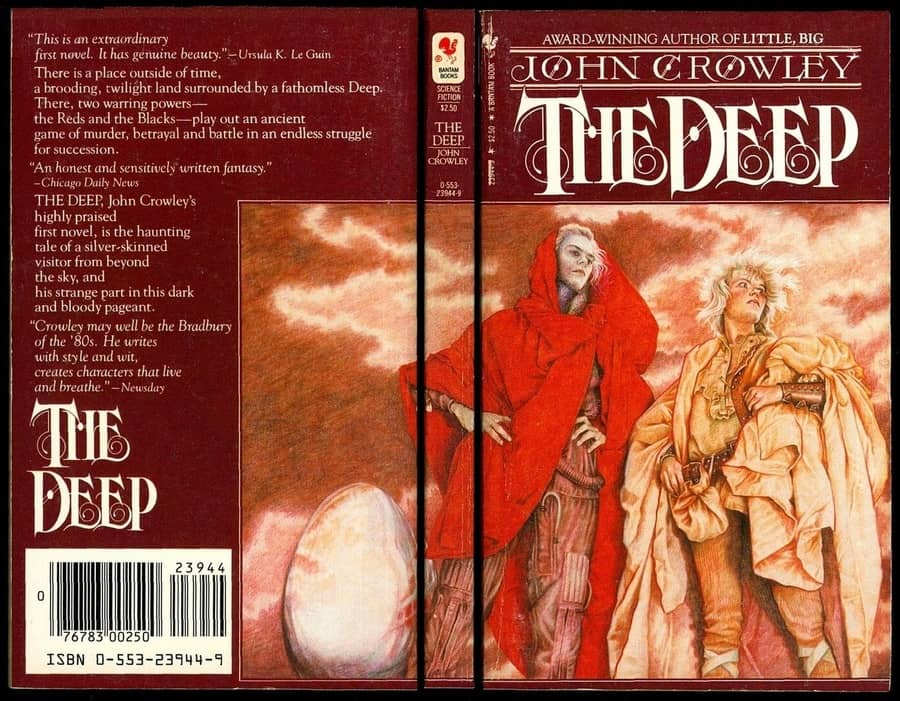

A Slender, Forgotten Gem: The Deep by John Crowley

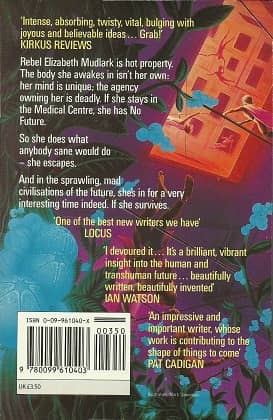

1984 Bantam paperback edition; cover by Yvonne Gilbert

Some authors create slender, nearly flawless works of fiction. Books like little jewels on the shelf — cut just right, gleaming, standing alone. Beagle managed this a few times: A Fine and Private Place, The Last Unicorn. Goldman turned his into a movie that was nearly as good: The Princess Bride. Swanwick and Wolfe have done it with literary science fiction: Stations of the Tide and The Fifth Head of Cerberus, respectively. The Deep is a book like this: finely wrought, chiseled, alien.

Is this tiny 1975 volume science fiction or fantasy? On the one hand, the book starts with the Visitor, a damaged android who arrives in the book’s world with no memory of what he is or his mission. But the world he’s in, the culture and factions of which his ignorance provides the perfect excuse for a narrator’s artful explanation, is purely fantasy: a kingdom riven by conflict between Reds and Blacks, with a city at its center and wild wastes surrounding, ringed on all sides by the Deep.

The world, as different characters explain at different times, is a platter or a plate suspended on the Deep by a great pillar. And even when the android journeys to the edge of this world and meets the Leviathan who dwells there, when he learns the nature of the engineered conflict and how humans were first settled on the world, Crowley doesn’t ever default to pure science fiction. Even if the reader can credit a resettled humanity in the far future, reset to medieval technology with continual wars to control the population, the story still leaves you with a flat world upon the Deep. Somehow, this central oddity works; it keeps a surreal wrinkle in the heart of the world Crowley creates.