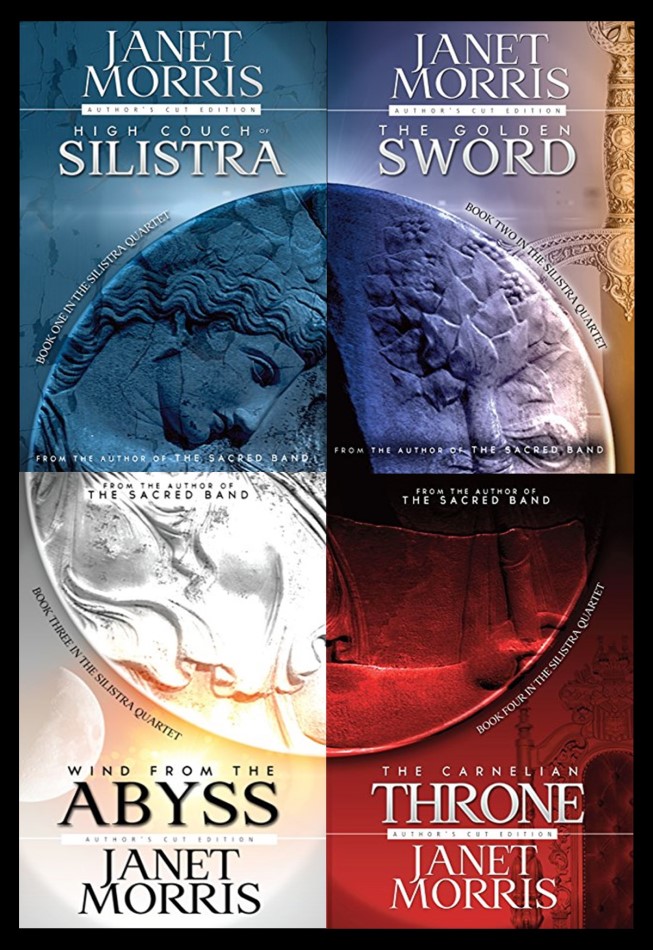

IMHO: A SECOND LOOK — The Silistra Quartet by Janet E. Morris

Janet Morris is a prolific author and has published a library’s worth of fantastic novels, enough to keep a reader busy for years. She has written everything from science fiction and heroic fantasy, to historical fiction and modern-day thrillers, many of them in collaboration with her husband, Chris Morris. Among her many novels are Outpassage, The 40-Minute War, The Kerrion Empire Saga, The Beyond Sanctuary Trilogy, and The Sacred Band. In addition, Janet and Chris were among the original writers who contributed to Thieves’ World ™, the shared-world fantasy series first published by Baen Books in 1979. In 1986, the duo created, Heroes in Hell ™, their shared-universe series of anthologies and novels; they also edited and contributed stories to this Saga of the Damned. That series was first published by Baen Books, and ran from 1986 to 1989. In 2011, Perseid Press “resurrected” the series, and it has been going strong ever since. But I digress.

…