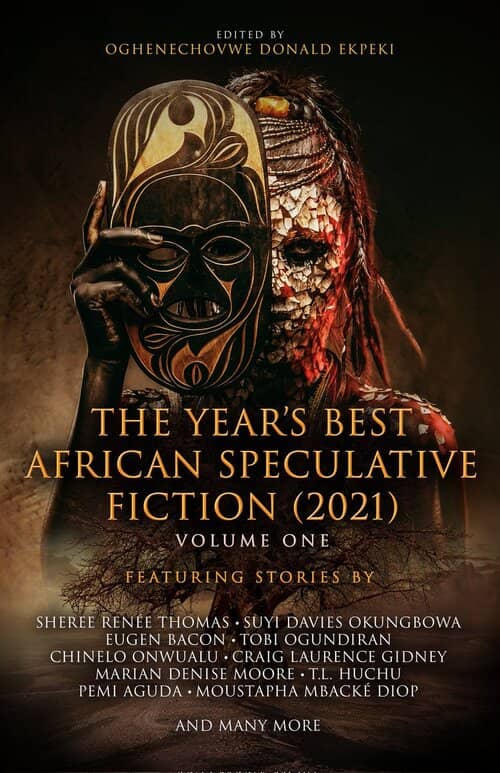

In 500 Words or Less: THE YEAR’S BEST AFRICAN SPECULATIVE FICTION, VOLUME ONE, ed. by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction

edited by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

Cover design by Maria Spada

Jembefola Press (358 pages, $6.99 eBook, Sept 28, 2021)

So… it’s about freaking time we have one of these, right?

Having already demonstrated impressive editing chops with Dominion (co-edited with Zelda Knight), Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki has created an even greater anthology with this Year’s Best, distilling twenty-nine stories into one of the most cohesive anthologies I’ve ever read. Common threads make this feel like so much more than just a “here’s who we think are the top authors” sort of Year’s Best. We’re being shown part of what African SF is saying right now, and honestly, we should feel lucky to be given this insight.

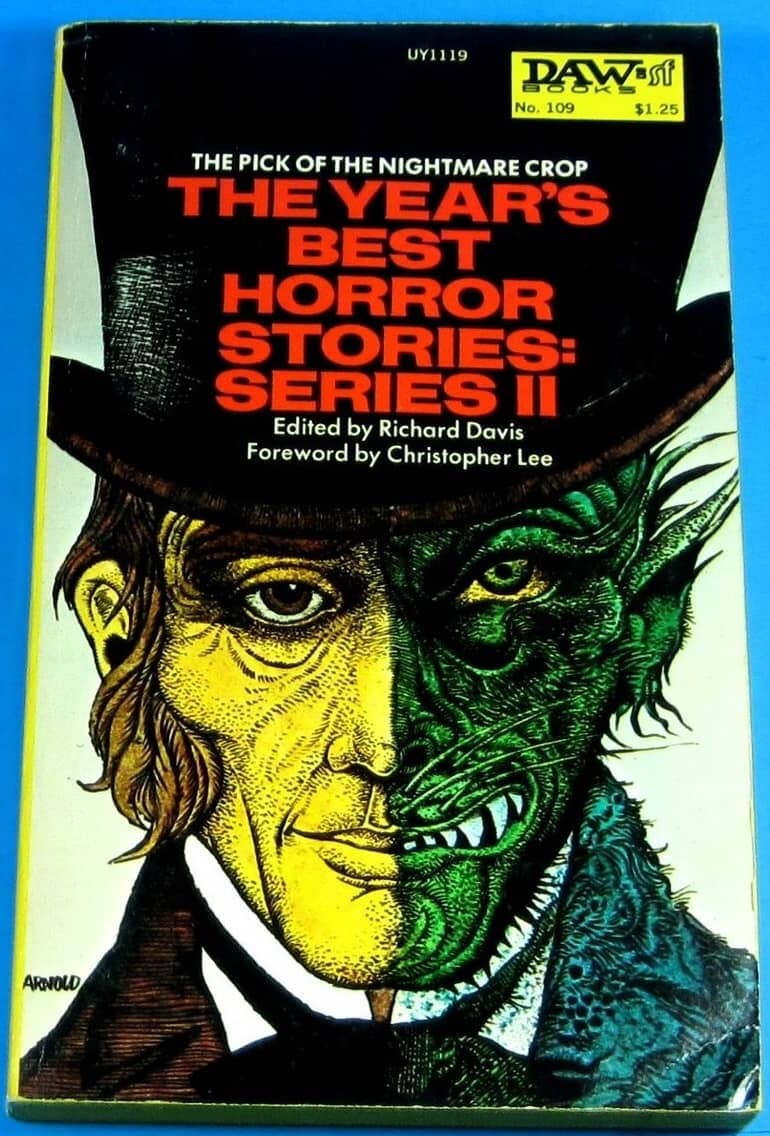

You ever watch one of the long video game cutscenes that passes for movies these days and think “I kinda miss old, raw-looking films, like early Romero and Carpenter. Something that had teeth. Heart. Balls. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”

You ever watch one of the long video game cutscenes that passes for movies these days and think “I kinda miss old, raw-looking films, like early Romero and Carpenter. Something that had teeth. Heart. Balls. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”