The Dream of the Numinous: Carl Sagan’s Contact

Contact by Carl Sagan

First Edition: Simon and Schuster, October 1985, Jacket painting by Jon Lomberg

Contact

by Carl Sagan

Simon and Schuster (432 pages, $18.95, Hardcover, October 1985)

Jacket painting by Jon Lomberg

Carl Sagan is known as the greatest science popularizer who was also a legitimate scientist of the late 20th century. His landmark achievement was a 13-part TV series, Cosmos, broadcast in 1980, and its companion book of that same year. Sagan was an astronomer and planetary scientist, whose achievements included planning the first Mariner mission to Venus in the 1960s and the Viking landers on Mars in 1976. His first popular book, The Cosmic Connection (1973), won a special nonfiction John W. Campbell Memorial Award – the only time that award went to a nonfiction book – in 1974. Indeed, that’s how I first heard of Carl Sagan, having been following the science fiction awards for just a year or two, at my age then.

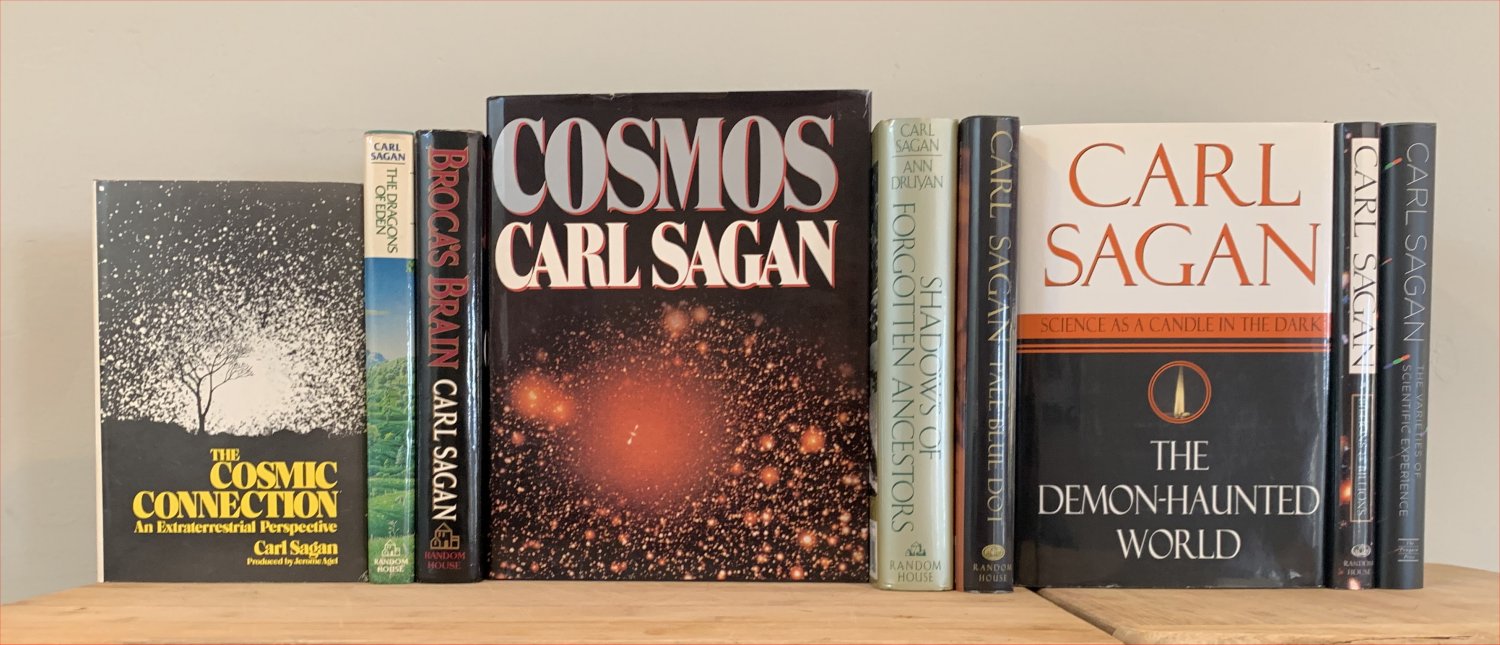

Nonfiction books by Carl Sagan:

The Cosmic Connection (essays) (Doubleday/Anchor 1973); The Dragons of Eden (Random House, 1977); Broca’s Brain (essays) (Random House, 1979); Cosmos (Random House, 1980); Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (with Ann Druyan) (Random House, 1992); Pale Blue Dot (Random House, 1994); The Demon-Haunted World (Random House, 1995); Billions & Billions (essays) (Random House, 1997); The Varieties of Scientific Experience (Penguin, 2006)

Following The Cosmic Connection, Sagan went on to write another dozen plus books (many shown above). With the success of the TV series and book Cosmos, he and his new wife (his third) Ann Druyan, drafted a movie script called “Contact.” It didn’t get into production, so Sagan wrote a novel version of that script, which is the book I’m examining here, published in 1985. It was a bestseller; its publisher paid a huge amount in advance based on Sagan’s popularity. It was decently reviewed, and won a Locus Award (reader poll) for best first novel, but was not a Hugo or Nebula nominee.

Contact owes an obvious debt to James Gunn’s The Listeners, reviewed here last April. Gunn claims that Sagan admitted that debt, in person, though Gunn’s name does not appear in the acknowledgements of Contact. Yet Sagan’s debt to Gunn is incidental. Gunn was speculating on the idea of SETI, and the motivations of those who searched, based on developments at the time captured in book and news media. Sagan actually did SETI. Among other things, he co-wrote the Arecibo Message sent out from Earth in 1974. Still, there are several crucial similarities between the two novels, which I’ll mention below.

The book was made into a film, some 12 years later – Contact, with Jodie Foster and a young Matthew McConaughey – based on Sagan’s book, not Sagan and Druyan’s earlier film script. (Though Druyan has a cameo, and both Sagan and Druyan are credited as producers. Sagan died in 1995, presumably as the film began production.) I’ll have some comments about the differences between book and film at the end of this review, but will not review book and film side by side as I did with Asimov’s Fantastic Voyage earlier this year.

The book:

Gist

SETI scientist Ellie Arroway, after years of searching, detects a signal from Vega that, once decoded, gives instructions for building a Machine. To do what? Travel to Vega? After a first Machine is destroyed by saboteurs, Ellie and four others become passengers on a second Machine, which takes them through wormholes to contact extraterrestrials who take the forms of people they love, and provide Ellie with a crucial clue about the nature of the universe.

Take

This is a serious novel about the scientific quest and the profound impact contact with intelligent extraterrestrials would have on the human race. It’s full of fascinating speculative asides, and its core speculative premise is profound in the best sense-of-wonder way. If it’s a tad more clinical than dramatic, it’s also deeper and subtler than Gunn’s novel, or the (albeit mostly admirable) film version.

Detailed Summary [[ with comments ]]

The novel, at 430 pages, is twice as long as Gunn’s The Listeners, and comes with similar philosophical heft – quotes from great philosophers and scientists, though in Sagan presented as chapter epigraphs. Given its investment, publisher Simon and Schuster indulged in a bit of special pleading on the dust jacket flap – “Contact goes far beyond the conventional limits of science fiction. It is a real, moving novel, a work of fiction at once deep and entertaining that carries the reader, like its protagonists, to the stars, without ever making us doubt that this is the way it will be. Not since H.G. Wells…” and so on. But we cannot hold the author responsible for publisher hype.

The book sold 1,700,000 copies in its first edition and, if it hasn’t become quite a fixture of the science fiction canon, it remains available and in print after 35 years, most recently (per ISFDB), from Gallery Books in 2019.

If you’ve only seen the film, I’ll summarize the principal differences between film and novel very briefly right here: In the novel, the ship built from the alien Message holds five people not just one; its design is a dodecahedron (as seen briefly in the film) and is surrounded by three whirling hoops, though not nearly so large; and Ellie’s contact with the Vegans provides her a clue about a message hidden in the transcendental number pi. The book’s conclusion is better, subtler, than the film’s.

Part I: The Message

1, Transcendental Numbers

- The first four chapters begin with italicized passages about a huge object in space, one we gather is an automated radio telescope that detects signals and reflects them back to their source.

- We then get a brief, episodic history of Ellie Arroway as a teenager: fixing an old radio, gazing at the stars, reading Twain, learning about transcendental numbers like pi. Her father Theodore Arroway dies, and she doesn’t understand her mother’s attraction to her new husband, John Staughton.

2, Coherent Light

- Ellie gets by in school without excelling, attends anti-Vietnam war rallies and rejects Bible class, gets a scholarship to Harvard, passes through a chain of boyfriends.

- The Soviets land on Venus and destroy her childhood fantasies of crystal cities there. She graduates and heads to CalTech to do radio astronomy, apprenticing to David Drumlin, brilliant but insecure that he may not be the smartest man in the room, and meets Peter Valerian, who’s fascinated by ETs (each faculty member is allowed one foible, Sagan observers), and who speculates about how different aliens might be.

- Ellie gets an appointment at Arecibo, and ponders SETI when Valerian visits. What are the odds? Perhaps ETs are out there, but simply not trying… like ants.

3, White Noise

- Ellie becomes director of Project Argus, 131 radio telescopes in the New Mexico desert, dedicated to SETI.

- No messages are detected, for years. Ellie listens to the static, dreams of sounds, hearing bits of melody.

- Drumlin, who never supported Ellie’s interest in SETI, arrives for a visit, with a letter suggesting that SETI be terminated and the facility returned to conventional radio astronomy. He holds a colloquium on the idea that there are no extraterrestrials, anywhere.

- Ellie goes for a drive out across the desert in her 1958 Thunderbird. [[ In the film it’s a ‘60s Chevrolet. ]] She watches Alpha Centauri, spots rabbits along the highway at night, listens to white noise.

- She wonders, suppose the message came in very slowly? Or very quickly? She can’t take Drumlin’s thesis seriously; it’s too much like the geocentric solipsism that has always placed humanity at the center of the universe.

4, Prime Numbers

- Finally a signal is detected, noticed by a night shift officer, while Ellie is talking on the phone to her mother in a nursing home. The signal seems to be coming from Vega. Could this be a joke? Vega is too young a sun to have planets and an intelligent civilization, they figure.

- They rule out noise interference, and (secret government) “dark satellites.” They notice the signal consists of repeated prime numbers – the classic SETI strategy, since no natural phenomenon could produce prime numbers.

- Ellie contacts an Australian radio observatory by phone. Then a teletype message (p81b) is sent out to all radio facilities in the world, to look at particular coordinates, and report.

5, Decryption Algorithm

- Visiting scientists gather at Argus; reporters are discouraged. Kenneth der Heer, the presidents’ science advisor, also visits; Ellie explains why prime numbers are a beacon, an announcement signal. They find the same signal in other frequencies.

- Michael Kitz, an assistant secretary of defense, wants the information in the message classified (even though they’re only prime numbers!) and any follow-up message to be kept quiet. He alludes to Ellie something about the “Hadden decision,” a legal ruling that allows the government to classify new discoveries.

- Polarization in the signal reveals a deeper message, billions of bits long, its length a product of three prime numbers. Easily decoded, Ellis and the others watch as a picture forms… And suspect this is all a hoax. The image is of Adolf Hitler, at the opening of the 1936 Olympics.

6, Palimpsest

- In Washington, Ken briefs the president (a woman), having to explain how Earth’s signals have gone out into space for decades. The President is flabbergasted, and mortified, that the earliest strong signal the ETs got was of Hitler. She’s advised that there’s little likelihood of this signal having anything to do with UFOs. [[ Another favorite Sagan topic, which he has challenged in his books since the 1960s. ]]

- Ellie and Valerian arrive, reporting that there’s yet a third message in the signal, under the others: huge blocks of information, thousands of blocks, or “pages,” which they presume the senders want us to understand.

- [[ There’s an aside, p110: “Maybe their planet will be destroyed. Maybe they want someone else to know about their civilization before they’re wiped out.” A nod toward Gunn’s novel, perhaps. ]]

- Ken points out an implication of the Earth’s rotation—they’re losing data whenever Vega’s not in the sky. They need the cooperation of other nations.

7, The Ethanol in W-3

- As news gets out to the public, crowds gather along the road to Project Argus—mystics and nuns, a wide variety of people.

- Around the world, religious and political sects offer their own opinions: the Message is from God; from the Devil; from the Nazis; it heralds the end of the world; or the return of Jesus, or Krishna, or Buddha; some worry whether the Vegans will dutifully denounce Trotsky. (pp124-126.)

- Meanwhile Ellie greets a colleague from Moscow, nicknamed Vaygay. Sagan indulges in background about Soviet relations, how some of their scientists are never allowed to the West, or they would never come back; about their spacecraft; about dinners in Moscow, about alcohol, about the ethanol content of galactic cloud W-3.

- As Ellie drives toward the facility, one roadside speaker stands out, railing to a crowd about how scientists are holding out on the public, how they are unbelievers, communists (p128b), and shouldn’t be allowed to determine the fate of the world. “The evil in this place will be stopped. I swear it.”

8, Random Access

- Ellie watches TV, noting a wide range of programs: sports, sex, video games; political news; “Yesterday’s News”; cooking shows; ads for robots, for real estate; religious networks. [[ Sagan is very prescient here, in the years before widespread cable TV. ]]

- Church attendance has soared; the Message confirms everyone’s beliefs. About UFO groups, Chiliasm. On certain channels Ellie and der Heer and Valerian are denounced, while Drumlin made out the hero.

- An evangelist, Palmer Joss, comes on TV to question science, talking about how people were happier in a simpler age, how theories are just guesses, how laws give way to other laws, how scientists rob humanity of spiritual value. (pp135-137) [[ Sections like this one are nothing if not thorough, but perhaps go on a little too long. Still, Sagan presents cases like these fairly, with little overt editorializing. ]]

- Then Sagan provides five full pages (pp137-142) of background about Palmer Joss. He began as a carnival roustabout; was struck by lightning, has a near-death experience, and recovers. He’s reborn. He studies scripture, under Reverend Billy Jo Rankin. The younger Rankin preaches about the healing powers of amniotic fluid, and Joss rejects him as a scam artist. He denounces various deviant forms of Christian fundamentalism. But he dismisses various scientific ideas too: age of the earth, relativity. He attacks what he thinks are excesses on both sides. In trying to reconcile both sides, he outrages both. He becomes the preeminent Christian fundamentalist preacher of his day.

- Now, Ellis fixes dinner for Vaygay at her apartment. They talk about Joss. Should they reach out to him? His buy-in would mean a lot.

- Vaygay is concerned that a power failure would lose part of the Message; they need redundant power and equipment. He has one other concern: he guesses, via references between the “pages” of the third signal, that the Message is instructions for building some kind of machine.

9, The Numinous

- Ellie falls in love with Ken der Heer. She does note possible character flaws, e.g. at the Vietnam War Memorial he’s overly preoccupied by a caterpillar. She ponders how humans dehumanize the enemy. He more or less moves in with her. She thinks about the number of things in the universe, of intelligent beings. She comes across an article about the ‘numinous’: “The theologians seem to have recognized a special, nonrational—I wouldn’t call it irrational—aspect of the feeling of sacred or holy. [He] believed that humans were predisposed to detect the revere the numinous…”

- [[ It’s significant that, while a core theme of the book is science vs. religion, and Sagan ably marshals the arguments for science, he leaves the door open for some kind of perception of a higher reality, something subtler than ordinary, irrational faith. ]]

Part II: The Machine

Ch10, Precession of the Equinoxes

- Joss refuses to come to Argus, insisting instead a meeting be held at a Bible Museum in Modesto. Billy Jo Rankin is there too.

- Virtually this entire chapter is a (familiar) debate about religion vs. science, faith vs. evidence. Joss rails against scientists as mistrusting everything and ruling out almost everything about religion.

- Ellie responds, p166, about avoiding mistakes, how conflicting religious beliefs can’t all be right.

- Rankin goes on about prophecies fulfilled; Ellie interjects about the different lineages of Jesus in the Bible. She goes on about how those prophecies are vague, open to fraud, that Rankin quotes only those he thinks have been fulfilled, and ignores the rest. Why didn’t God leave something to make his existence unmistakable, e.g. bits of basic scientific knowledge in the Bible? Why not unambiguous signs of His presence today? Why has God abandoned us?

- This goes on until Rankin gets quite worked up. They pause for lunch.

- After which she explains how she admires Jesus. He asks if she believes in God. She talks about hypotheses and being agnostic. Everyone all over the earth is getting the Message, not just the Christians. They move on to discussing the message. Anything special about Vega? Well, it was the north star 12,000 years ago (due to the precession of the equinoxes), about the time people were crossing the Bering Strait from Asia to North America. Rankin is impressed by this—it must be Divine Providence.

- [[ Needless to say, this kind of detailed debate is left completely left out of the movie ]]

Ch11, The World Message Consortium

- The Message is now sending diagrams, and news of it is all over the world. There are signs of global unity: agreements are reached to dismantle nuclear weapons.

- A World Consortium is held in Paris, with delegates from many nations. Ellie and Vaygay give opening summaries. A Soviet delegate worries that the machine might be a Trojan Horse, or a Doomsday Machine. And Indian delegate counters that the inevitable vast difference in technological abilities means that humans would be no threat to the Vegans.

- Ellie shows the now complete 3-D diagram of a Machine from the third signal: a large dodecahedron, with five armchairs inside.

- The Chinese delegate says they cannot go back. If the idea of the Machine is so frightening, then build it somewhere like the Moon. The Message is an invitation, which it would be impolite to refuse.

Ch12, The One-Delta Isomer

- Elli and the Indian delegate, Devi Sukhavati, walk through Paris. Cannabis is legal here; one strain is called the 1-delta isomer, “Sun-Kissed.” Devi talks about ancient names for Vega, how different groups regarded various names as either God or Devil.

- The Americans debate about building the Machine. One reason for building it would be for the new technology, the economic value. Another issue: which five people? Russians, Americans? How many of each sex? Vaygay explains how Russians, in their history, had it harder than Americans, and so have learned to become cautious. The conclusion is the message was for the whole planet, so the Machine should be built by the whole planet. One of the Russians worries this could all go horribly wrong, like peasants invited to the fancy party, where they are laughed at, and shown who their betters are.

Ch13, Babylon

- At Argus a Cray 21 continues to compare new data to old, piecing things together. Ellie reflects how half the scientists on the planet work in the military.

- Then they detect that the message is starting to recycle. This is alarming because, knowing that they missed the very beginning of the message, they’d assumed, or hoped, that once it recycled to the beginning there would be a “primer” with instructions for decoding the rest. But there’s no primer. What does this mean? Perhaps there is a fourth layer to the palimpsest?

- Seeking help, Ellie comes to a Ziggurat, a huge recreational park in the New York City area, called Babylon, the home of the reclusive Mr. Hadden. He has become wealthy by developing various context-recognition chips (that would, e.g. mute TV commercials, or preachers: Adnix and Preachnix) that was the subject of the legal case mentioned earlier in the book. He put the TV networks out of business.

- They discuss ideas about the primer. Data rates, modulation; perhaps only detectable from space.

- Now he’s wealthy and bored, and he wants to build the Machine himself. He dismisses Rankin and Joss as jackals.

Ch14, Harmonic Oscillator

- The primer has been found, in the phase modulation of the Message. Der Heer explains it to the President, showing her simple examples (p237) of how strings of characters define true, false, equals. How they go on to define the periodic table, atoms and particles, quantum mechanics, even about how to mine erbium, which for some reason must be significant.

- The Message, it turns out, has huge redundancies, but describes how to build the Machine.

- Meanwhile agreements on crew selection have been worked out. Americans have one seat. Who to pick? It boils down to Arroway or Drumlin. Each of them testifies before a Congressional selection committee. Ellie gives a tactless answer to the question of overpopulation. Drumlin talks fervently about emotions and evolution.

- Later Palmer Joss invites Ellie to meet him at a museum, where he invites her to test her “faith” in physics with a Foucault pendulum. Despite herself, she flinches.

- Outside he tells her about his near-death experience. Ellie counters with possible explanations. They debate about how to behave if there’s no God, about not being central to the universe, about goodness and cruelty. She thinks about him, “His god is too small! One paltry planet, a few thousand years—hardly worth the attention of a minor deity, much less the Creator of the universe.”

Ch15, Erbium Dowel

- The machine is built, over years and with trillions of dollars. Two are built, one in the US, one in the USSR, consisting of three spinning spherical shells. The Soviets have trouble; Sagan discusses Lysenko in the USSR, fundamentalist anti-evolutionists in the US, p274.

- Drumlin is selected, not Ellie. Earth-firsters burn Babylon, as the Message continues, and people speculate about alien motives.

- During a walk-around before a test of the US Machine, an explosion sends everyone flying into the air. The Machine is destroyed. Various groups take credit. Investigation shows that one of the erbium dowels broke. Plastic explosives indicate an inside job. The explosion has killed Drumlin. Ellie thinks he saved her life, but declines to speak at his funeral. She realizes circumstances have made her the candidate for the expedition. Even as she realizes she’s hated Drumlin all along.

Ch16, The Elders of Ozone

- Ellie launches into orbit to visit Hadden, now on the Methuselah. It’s been found that zero gravity extends the lifespan; now the wealthy can live in orbital retirement hotels to survive an additional decade: Conspiracy theorists on Earth imagine the wealthy’s Protocols of the Elders of Ozone.

- [[ Some of this speculation about how Earth matures into a single world, including the reduction of arms, parallels the optimistic social developments in Gunn’s novel. ]]

- Hadden speaks philosophically about how Earth might be someone’s object lesson, checked every few million years until an alarm is set off. And he reveals that a copy of the Machine is being built in Japan. Would she like to go? He cautions her that immortals would be very risk-averse, and how everything would be an unacceptable risk.

Ch17, The Dream of the Ants

- Ellie learns that her mother has had a stroke, and chastened by a letter from John Staughton, visits her now, confined to a bed, able only to blink.

- Then she arrives at the Hokkaido Machine site, and learns about Xi, the terra-cotta army, and Qin, great but mad.

- Ellie and Vayagay have dinner with a Buddhist abbot, who discusses communication; to understand the language of ants, you must become an ant.

Ch18, Superunification

- In Hokkaido Ellie learns of the Ainu people; visits a festival in Sapporo; meets Eda, the discoverer of the superunification theory; attends another festival in Tanabata, and hears a fable about a young couple representing Vega and Altair.

- The plan is to launch the Machine on the last day of December 1999. They select equipment, clothes, cameras. Ellie wants to take a palm frond.

- On that day, vacuum is drawn, the spherical shells spin, they come up to speed, the walls flicker, and to Ellie inside the Machine it seems the Earth opens up and swallows her.

Part III: The Galaxy

Ch19, Naked Singularity

- Their Machine, the dodecahedron, has gone transparent. They fall, as if through a dark tunnel. Into a black hole? The walls of the tunnel squeeze them forward. They emerge into ordinary space, near a blue-white sun: Vega.

- They see no planets, but do see a huge cluster of radio telescopes, pointing in many directions. Is Vega only a guardhouse? They see spots of many black holes. [[ A little like Clarke’s Grand Central Station in 2001, p341.4. ]] They approach a larger black hole, and plunge into it. And emerge into a system of contact-binaries. And so on through a series of black holes, two in each system. Hours pass. They emerge into a sky full of stars, and huge artifact, full of doorways, docking ports, for different sizes of ships. Their dodecahedron approaches a matching port, and docks in perfect silence.

Ch20, Grand Central Station

- Their airlock opens, and they emerge onto a beach, with waves, clouds, palm trees, and one sun in the sky. It could be Earth. Their dodec Machine disappears.

- Night comes. They build a fire, as the stars come out, with all the familiar constellations.

- They wake, in the morning. They find a doorway in the sand; from behind it’s not there. Do they go through? One by one, the others go, leaving Ellie for last.

- She sees someone walking toward her on the beach—it’s her father! She runs into his arms. Somehow she knows this is all a trick, but it’s flawless. She asks him if he knows the meaning of this test. He replies, from her dreams.

- –This section is the speculative, sense-of-wonder core of the novel:

- Her father says, they’re like a galactic census. They enable cultural exchange. They don’t interfere with hostile cultures; aggressive civilizations usually destroy themselves. They were impressed by human music, e.g. Beethoven.

- What do they think of humans? He replies plainly (see passage quoted below for p360.3). She can’t tell anything about who is behind this portrayal of her father. She refrains from asking him metaphysical questions.

- He shows her the transportation system—abruptly viewing the galaxy from the top, its arms, and a network of straight lines, the system. Various clouds, the two black holes at the center of the galaxy. The stuff pouring into them winds up, he says, in Cygnus A. A cooperative project of many galaxies. The universe hasn’t been a wilderness for billions of years. The basic problem is the universe is expanding, so after a while, there is nothing new, no new galaxies or stars. So they’re experimenting with making something new.

- And they didn’t build any of those subways. Species from many worlds found them, created by some vanished earlier builders, vanished no one knows where. They are just caretakers.

- One more question: what are their myths, religions? p366. He offers an example: about pi, which cannot be calculated to the last digit, since there is no last digit. Somewhere out in the ten-to-the-twentieth power place, the random digits disappear, and there’s a long string of nothing but ones and zeros, 366b. The number of them is the product of eleven primes. Built into the fabric of the universe. Waiting for creatures with ten fingers to come along and discover it. What does it say?

- He doesn’t say. The others have come back to the beach. With relatives. All of their deepest loves.

- The Caretakers are in a bit of a hurry. The five are taken to the airlock of the dodecahedron. Eda has been told about a different transcendental number, not pi or e. Apparently the messages in those numbers have not been decrypted.

- Time to go. The link will be left open, but only for inbound traffic. Ellie reflects that the experience has been theological, these beings like gods. Except they have evidence.

- Her father tells her, she’s on her own. What does the message say? He doesn’t know; they don’t know.

Ch21, Causality

- And so Ellie and the others return to Earth. Only 20 minutes have passed. But they’re told something is wrong: the dodecahedron didn’t go anywhere. And there’s nothing on the microcassettes Ellie filmed. None of the others have physical evidence either.

- There are debriefings. Ellie’s interrogator Kitz gets hostile, dismissing her story as religiously inspired fantasy. Or a shared delusion.

- And yet: the dodecahedron does show evidence of various stresses. And the Message stopped the moment the Machine was activated. Evidence of conspiracy? Ellie gives reasonable responses to his crazed conspiracy thinking; she thinks this reveals Kitz as someone afraid or in pain.

- Kitz settles on making a neutral press release, stating that the project is going on ice, making no claims, but subtly threatening her if she goes public with her story.

Ch22, Gilgamesh

- Haddon has died. So the story is released. Actually, he has launched himself away in a small ship called Gilgamesh, in cryogenic sleep, trusting that someone will find him, someday.

Ch23, Reprogramming

- The five ponder; what can they do? They return to their lives. Ellie is awarded a Medal of Freedom. She’s allowed to return to Argus. Reporters pester them, but eventually fall away. She ignores her email. She launches a program to study Sagittarius A, Cygnus A.

- Palmer Joss visits her, and she tells him everything. She’s calculating pi, has written a program to search for strings of zeros and ones. How this would be an unambiguous message, if God is a mathematician. See 420.3

Ch24, The Artist’s Signature

- Ellie’s mother dies. John Staughton is there, hands her a letter from her mother.

- The letter is from 1964 and reveals that her real father is, in fact, John Staughton. Suddenly, she has to rethink her life. She was not ready, at age 15, to receive that signal.

- And finally, the Argus computer sends her a message: The anomaly shows up in base 11 arithmetic. A pattern of ones and zeros that, when properly displayed, reveals a circle of ones against a field of zeros. “The universe was made on purpose, the circle said.” And, “Standing over humans, gods, and demons, subsuming Caretakers and Tunnel builders, there is an intelligence that antedates the universe.”

Contact movie poster, 1997

Wikipedia

About the movie

- First of all, the movie imagines a romantic relationship between Palmer Joss and Ellie Arroway – despite their philosophical differences!

- In the film, the Machine hold only one person. In the book, five. Also, in the book there’s no dramatic “launch” that involves dropping the capsule from a gantry through the spinning hoops; the capsule is much smaller, and stationary, while the arrangement of spinning hoops is the same.

- A bit oddly, the book does not identify the source of the sabotage of the first Machine, perhaps to suggest a range of possible villains. The movie makes the culprit explicitly a religious zealot, a man we had seen ranting to the crowds along the highway into Argus.

- The thing that infuriated me when I first saw the movie, back in 1997, was the scene in which Arroway and Drumlin give testimony before the Congressional selection committee – atypically, a scene expanded from the couple excerpts in the novel. In the movie, Palmer Joss is part of the committee, and concludes the questioning by asking Ellie, “Do you believe in God?” Since after all 95% of people on Earth do. Shouldn’t someone be sent on this mission who represents 95% of humanity? And Ellie sputters, talking about empirical evidence. She’s given no good lines to say. When challenged, she just says, “I believe I’ve already answered that question.” She could have said, “As a scientist my religious beliefs are irrelevant; scientists draw conclusions based on empirical evidence.” Or she could have been rude and said, “Which one? Which of all the conceptions of God that, around the world, have driven religious conflicts over the centuries?” But the scriptwriters gave her nothing decent to say. That lets Drumlin – who shamelessly plays to the committee, and the public, by invoking his personal relationship with God – to win the round and be chosen as the passenger on the Machine.

- Positioning itself as a big-budget, important Hollywood film, it has a couple dozen prominent cameos of real people: Larry King, Geraldo Rivera, Jay Leno, Bryant Gumbel, Geraldine Ferraro.

Quotes

The orbiting genius Haddon, to Ellie, p287:

You see, the religious people—most of them—really think this planet is an experiment. That’s what their beliefs come down to. Some god or other is always fixing and poking, messing around with tradesmen’s wives, giving tablets on mountains, commanding you to mutilate your children, telling people what words they can say and what words they can’t say, making people feel guilty about enjoying themselves, and like that. Why can’t the gods leave well enough alone? All this intervention speaks of incompetence. If God didn’t want Lot’s wife to look back, why didn’t he make her obedient, so she’d do what her husband told her? Or if he hadn’t made Lot such a shithead, maybe she would’ve listened to him more. If God is omnipotent and omniscient, why didn’t he start the universe out in the first place so it would come out the way he wants? Why’s he constantly repairing and complaining? No, there’s one thing the Bible makes clear: The biblical God is a sloppy manufacturer. He’s not good at design, he’s not good at execution. He’d be out of business, if there was any competition.

An epigram quote by Cicero, to Chapter 17:

Popular theology… is a massive inconsistency derived from ignorance… The gods exist because nature herself has imprinted a conception of them on the minds of men.

The aliens speaking through Ellie’s father about what they think of humans, p360.3:

All right. I think it’s amazing that you’ve done as well as you have. You’ve got hardly any theory of social organization, astonishingly backward economic systems, no grasp of the machinery of historical prediction, and very little knowledge about yourselves. Considering how fast your world is changing, it’s amazing you haven’t blown yourselves to bits by now.

And p360.5:

You can see that, after a while, the civilizations with only short-term perspectives just aren’t around. They work out their destinies also.

Ellie questioning her father, p366:

Ellie: “I want to know about your myths, your religions…”

Father: “I’ll give you a flavor or our numinous. It concerns pi, the ration of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. You know it well, of course, and you also know you can never come to the end of pi. … None of you seem to know, let’s say the ten-billionth place… something happens. The randomly varying digits disappear, and for an unbelievable long time there’s nothing but ones and zeros.”

P420.3, after Joss hears Ellie’s story:

I’ve been searching, Eleanor. After all these years, believe me, I know the truth when I see it. Any faith that admires truth, that strives to know God, must be brave enough to accommodate the universe. I mean the real universe. All those light-years. All those worlds. I think of the scope of your universe, the opportunities it affords the Creator, and it takes my breath away. It’s much better than bottling Him up in one small world. I never liked the idea of Earth as God’s green footstool. It was too reassuring, like a children’s story… like a tranquilizer. But you universe has room enough, and time enough, for the kind of God I believe in.

Final Thoughts

This is a novel rich in ideas, including many off-hand speculations (as if Sagan were getting everything he could into this one work) that are incidental to the main story, but nonetheless fascinating.

And this is a novel that betrays a scientist’s, Sagan’s, belief in rationality and the orderliness of the universe, while nevertheless retaining a hope, or wish, that there might be some sign of a higher intelligence implicit at least in the very structure of reality. A far cry from the omniscience god who answered the payers of individual humans, but still… Is this a hope or dream? Or just another speculative premise? Perhaps Sagan’s notion of how a creating force (or species) would leave its signature, in as subtle a way as possible.

I think this is a book by a writer who knew he would write just one novel.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of James Gunn’s The Listeners. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

This deep dive into Contact is simply beautiful. Thank you for putting in the work to spread Sagan’s poetry…and dream of the numinous.

I’ve just started a podcast about the same topic: Sending Poets