Worlds Within Worlds: The First Heroic Fantasy (Part II)

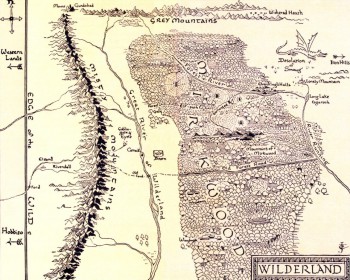

This is the second post in a series trying to answer what looks like a simple question: who wrote the first fantasy set entirely in another world? As I found in my first post, to answer that question you first have to decide how to define a fantasy otherworld. I came up with a list of four characteristics: whether the world has a distinct logic to it, such as the use of magic; whether the people in the world are meant to be perceived as residents of this world; whether the world has its own history; and whether it has its own geography. It seems to me most otherworlds have all four characteristics, with a few interesting cases getting by with three. Any less than three, and you don’t have an otherworld.

This is the second post in a series trying to answer what looks like a simple question: who wrote the first fantasy set entirely in another world? As I found in my first post, to answer that question you first have to decide how to define a fantasy otherworld. I came up with a list of four characteristics: whether the world has a distinct logic to it, such as the use of magic; whether the people in the world are meant to be perceived as residents of this world; whether the world has its own history; and whether it has its own geography. It seems to me most otherworlds have all four characteristics, with a few interesting cases getting by with three. Any less than three, and you don’t have an otherworld.

Now, traditionally, William Morris has been considered to be the first writer to have set a story entirely in a fantastic otherworld; that is, to write a story in which the real world as we know it never appeared. His was the name suggested by Lin Carter and L. Sprague de Camp, it was accepted by John Clute and John Grant in their 1997 Encyclopedia of Fantasy, and it’s found a place in the repository of all human knowledge, Wikipedia. I, however, am disagreeing; I’ve found an a writer from a few decades before Morris who wrote something that seems to me to be an otherworld fantasy.

Before naming that writer, though, I’d like to tackle a related question. And that is: why did it take so long for somebody to come up with the idea?

Consider: Morris’ The Wood Beyond the World was published in 1894. Even if the first otherworld fantasy was in fact a few decades earlier, then people were still telling tales for thousands of years before coming up with the idea of an independent world (it would be interesting to see when the term ‘world’ began being used in criticism, as in ‘the world of Dickens’ or ‘Shakespeare’s green world’). Why the long delay?

Let us die in the doing of deeds for his sake;

Let us die in the doing of deeds for his sake; 3. The Saxon Stories, Bernard Cornwell. Uhtred of Bebbanburg is a Saxon youth captured and raised among the Danes, who then proceeds to spend the next several books in this yet-unfinished series fighting alternately for both sides in war-torn 9th century England. The Saxon Stories features Cornwell, a brilliant historical fiction writer, at his near-best (though I still prefer his Warlord Trilogy) with Viking raids, shield walls, axes, dark ages combat, hall-burnings, and general mayhem galore. Great stuff.

3. The Saxon Stories, Bernard Cornwell. Uhtred of Bebbanburg is a Saxon youth captured and raised among the Danes, who then proceeds to spend the next several books in this yet-unfinished series fighting alternately for both sides in war-torn 9th century England. The Saxon Stories features Cornwell, a brilliant historical fiction writer, at his near-best (though I still prefer his Warlord Trilogy) with Viking raids, shield walls, axes, dark ages combat, hall-burnings, and general mayhem galore. Great stuff. Who was the first person to write high fantasy?

Who was the first person to write high fantasy?

Warning: This essay contains some spoilers.

Warning: This essay contains some spoilers. Because this series about riding about the dragon called Publishing is geared at writers just starting out writing fantasy stories and novels, I thought I’d pull together

Because this series about riding about the dragon called Publishing is geared at writers just starting out writing fantasy stories and novels, I thought I’d pull together

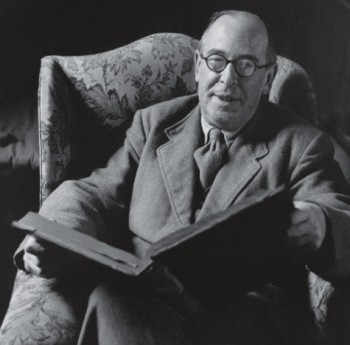

Though he’s best known as the author of the Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was also a prolific essayist and an ardent defender of fantasy literature. In addition to medieval studies (The Allegory of Love) and Christian apologetics (Mere Christianity), Lewis wrote several essays about the enduring appeal of

Though he’s best known as the author of the Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was also a prolific essayist and an ardent defender of fantasy literature. In addition to medieval studies (The Allegory of Love) and Christian apologetics (Mere Christianity), Lewis wrote several essays about the enduring appeal of  Freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility are steep slopes; he could not climb them for us—we must do that ourselves. But he has shown us the road and the reward.

Freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility are steep slopes; he could not climb them for us—we must do that ourselves. But he has shown us the road and the reward.