Wolfe’s lost road: Discovering an author’s personal essay on J.R.R. Tolkien

Freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility are steep slopes; he could not climb them for us—we must do that ourselves. But he has shown us the road and the reward.

Freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility are steep slopes; he could not climb them for us—we must do that ourselves. But he has shown us the road and the reward.

–Gene Wolfe, “The Best Introduction to the Mountains”

J.R.R. Tolkien has so many readers, and his works have become so pervasive in the broader culture, that coming to his defense hardly seems necessary anymore. Haven’t we established Tolkien’s credentials by now? Magazines like Time have selected The Lord of the Rings as one of the top 100 novels ever written, according to Wikipedia it’s one of the top 10 best-selling books of all time with 150 million copies sold, and the movies upon which it’s based won several Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Tolkien has made it onto several college syllabi and there are academic journals and numerous critical studies devoted to his works, including Tom Shippey’s par excellence works Author of the Century and The Road to Middle-Earth.

But someone always comes along to attack Tolkien on the basis of his conservatism or religion, his perceived racism, and/or the perceived shallowness/non-literary nature of The Lord of the Rings, and I’m reminded of why we need to vigilant. For example, David Brin of Salon.com, Science fiction/fantasy author Richard Morgan (author of The Steel Remains), and Philip Pullman (author of the His Dark Materials trilogy) have all taken shots at The Lord of the Rings and/or Tolkien himself in recent years, calling him outdated and dangerously conservative (Brin), a refuge for 12-year-olds and adults who have never grown up (Morgan), and shrunken and diminished by his Catholicism (Pullman).

Now I’m not saying Tolkien is above criticism, but critics like Brin and Morgan have essentially gutted The Lord of the Rings, attacking it on an existential basis and more or less claiming it should be placed in the dustbin of history. When people take aim at classics like Ulysses or Moby Dick you rarely see criticism elevated to the level of calling into question the very existence of these works. Yet Tolkien criticism for whatever reason frequently ascends to shrill peaks of outrage.

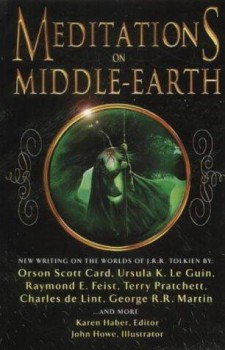

Which is why Tolkien’s fans and readers will probably forever have to take up Andúril and step into the shieldwall to defend the good professor’s works. Fortunately, much of the legwork has already been done in works like Meditations on Middle-Earth. Published in 2001, Meditations is a collection of essays about Tolkien by a host of bestselling fantasy and science-fiction authors, including George R.R. Martin, Poul Anderson, Terry Pratchett, Robin Hobb, Ursula LeGuin, Douglas Anderson, Orson Scott Card, Charles De Lint, and Terri Windling, among others. Some of the essays are inspiring and illuminating, others mere fun anecdotes about discovering Tolkien, but all share one thing in common: A profound respect for the man who pretty much put fantasy on the map. Yes, I know works like The Well at the World’s End and The King of Elfland’s Daughter predated The Lord of the Rings, but it was Tolkien who elevated fantasy into the mainstream. Without the market Tolkien created, many of these authors would never have seen print.

Which is why Tolkien’s fans and readers will probably forever have to take up Andúril and step into the shieldwall to defend the good professor’s works. Fortunately, much of the legwork has already been done in works like Meditations on Middle-Earth. Published in 2001, Meditations is a collection of essays about Tolkien by a host of bestselling fantasy and science-fiction authors, including George R.R. Martin, Poul Anderson, Terry Pratchett, Robin Hobb, Ursula LeGuin, Douglas Anderson, Orson Scott Card, Charles De Lint, and Terri Windling, among others. Some of the essays are inspiring and illuminating, others mere fun anecdotes about discovering Tolkien, but all share one thing in common: A profound respect for the man who pretty much put fantasy on the map. Yes, I know works like The Well at the World’s End and The King of Elfland’s Daughter predated The Lord of the Rings, but it was Tolkien who elevated fantasy into the mainstream. Without the market Tolkien created, many of these authors would never have seen print.

As a fan of Haber’s book I was pleasantly surprised to happen across “The Best Introduction to the Mountains” by Gene Wolfe during a recent web search. As it turns out, Wolfe had submitted the essay for Haber’s consideration in Meditations on Middle-Earth but was rejected. Fortunately Andrew Robertson, a former editor for Interzone, later published the essay for the magazine and has since posted it to his personal website.

For those who don’t know Wolfe he’s the author of works like The Book of the New Sun and The Wizard Knight. Among fantasy aficionados he’s known as one of the genre’s best writers. Literary and stylish are frequently used to describe his works, terms with which I agree wholeheartedly. Even though “The Best Introduction to the Mountains” never saw print in Meditations on Middle-Earth it serves as fine grist for the mill for those who love and value the works of Tolkien, adding another big-time name to the roll of authors who have drawn a lifetime of inspiration from The Lord of the Rings. Just like Martin and Hobb and Anderson, Wolfe also seems to have found something of lasting value in The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s other works.

Essentially, Wolfe’s says that The Lord of the Rings taught him that right and wrong can be absolutes, and that absolute moral equivalency is another piece of Mordor. In addition, it taught him that “progress” is not necessarily progressive, and with change comes inevitable loss. Says Wolfe:

It is said with some truth that there is no progress without loss; and it is always said, by those who wish to destroy good things, that progress requires it. No great insight or experience of the world is necessary to see that such people really care nothing for progress. They wish to destroy for their profit, and they, being clever, try to persuade us that progress and change are synonymous. They are not.

(As an aside, I also love the fact that Wolfe inscribed his dog-eared copy of The Return of the King with a quotation from Robert E. Howard. That’s just plain cool).

My only quarrel with Wolfe is with his belief that Tolkien also saw change as harmful in the main. I don’t believe that’s true. While Tolkien did experience nostalgia for the past, and mourned for the loss of a mythic time and a world drained of its magic, I would argue that Tolkien viewed change as not always bad, just inevitable, and “progress” as a harbinger of difference, not decay. Change can be for the better or the worse. Loss of individual freedom, increased mechanization and urbanization, the destruction of wood and field and stream—or the loss of native English language and mythology following the Norman invasion of 1066, to touch on a subject near and dear to Tolkien’s heart—are all reasons to treat progress with skepticism.

But Tolkien was not advocating a return to a mythic past, merely longing for something that once was, but will never be again. There’s a difference. As Tolkien scholar Michael Drout states in Rings, Swords, and Monsters, nostalgia is a longing for something you cannot return to (if you can reach the object of your longing, it’s not nostalgia, Drout says). Tolkien understood that change was inevitable, for better or worse, and works like The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion express a calm, mature, adult grief for that which is lost as an inevitable consequence of change. I don’t see what’s wrong with this viewpoint, nor do I understand how it can ruin one’s enjoyment of Tolkien’s works. It’s not childish or arch-conservative. Tolkien does not disdain nor rail against progress. His is a calm, adult, rational dislike of unbridled modernity. He knew it was inevitable. Frodo’s “triumph” at the mouth of Mount Doom was just a temporary victory. The world of men was coming, and with it great good and unspeakable evil. It’s nostalgia, true, but I would argue that Tolkien is not advocating for a return to monarchy in The Lord of the Rings. He knew that we’ll never have a being as perfect as Aragorn or Arthur to rule us, anyway.

But Tolkien was not advocating a return to a mythic past, merely longing for something that once was, but will never be again. There’s a difference. As Tolkien scholar Michael Drout states in Rings, Swords, and Monsters, nostalgia is a longing for something you cannot return to (if you can reach the object of your longing, it’s not nostalgia, Drout says). Tolkien understood that change was inevitable, for better or worse, and works like The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion express a calm, mature, adult grief for that which is lost as an inevitable consequence of change. I don’t see what’s wrong with this viewpoint, nor do I understand how it can ruin one’s enjoyment of Tolkien’s works. It’s not childish or arch-conservative. Tolkien does not disdain nor rail against progress. His is a calm, adult, rational dislike of unbridled modernity. He knew it was inevitable. Frodo’s “triumph” at the mouth of Mount Doom was just a temporary victory. The world of men was coming, and with it great good and unspeakable evil. It’s nostalgia, true, but I would argue that Tolkien is not advocating for a return to monarchy in The Lord of the Rings. He knew that we’ll never have a being as perfect as Aragorn or Arthur to rule us, anyway.

Finally, it bears repeating that Tolkien expressed a longing for a mythic past. He was not mourning the end of British colonialism, or feudalism, as some critics suggest, but a time far more ancient, the unrecorded First through Third Ages of our own (Middle) Earth. The former are crude allegorical interpretations of a much broader, deeper, and more subtle work.

So head on over and read Wolfe’s essay. Love or hate its conclusions, it’s yet another moving anecdote by one of fantasy’s greats that helps to explain Tolkien’s rise from obscurity and initial critical disdain to lasting cultural prominence and relevance. Thanks for being another shield in the wall, Mr. Wolfe.

An excellent article, Brian. Thank you for pointing me to Gene’s also excellent essay.

–Dave

I am reading lord of the rings for the first time right now. i’m half way through the two towers. I love every page…i wish i had never seen the movies before i read these books.

I have to admit, I’m part of the group that didn’t like The Lord of the Rings. I will certainly agree that they have historical importance to the genre, but I find them to be unreadable dross when I attempt to finish it for the sake of reading a genre classic. I was once reading a page (think it was one of those SF Signal MindMeld things) about over-rated fantasy works, and someone mentioned that Tolkien had interesting plots but wasn’t a great writer. I found myself agreeign with that in part. The scope and complexity of The Lord of the Rings is certainly an impressive feat, but the presentation, in my mind, was overburdened with excessive and useless details that slowed and/or stopped any plot progression, leaving me not caring a bit about whether the ring was destroyed or some orc finally (thankfully) ate Frodo.

I have enjoyed some of Tolkien’s other works, especially “Smith of Wooten Major” and “Farmer Giles of Ham.” His translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was also entertaining. I felt he was more effective at short length, giving us the plot without having room to escape the plot into triviality for ungodly lengths of time.

I highly doubt that the modern state of epic fantasy that Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings had a hand in creating would deem The Lord of the Rings as anything other than bloated and unpublishable if Tolkien had lived and worked today.

I don’t hate Tolkien, and I’m not knocking him “on the basis of his conservatism or religion, his perceived racism, and/or the perceived shallowness/non-literary nature of The Lord of the Rings.” Literature mainly seems to be a fine line that academics use to create an “acceptable” cannon, and I don’t subscribe to that. I’m attacking The Lord of the Rings on the basis that, despite great amounts of fame and impact, it just isn’t that good.

I mean, look at Twilight. Popular. Impacted the popular subgenres of fantasy. Isn’t that good.

It happens.

Thanks for the comments, all.

Dave: Yes, I was pleasantly surprised to find the essay and I’m not entirely sure why it failed to make the cut in Meditations on Middle-Earth. There are better essays in that book but Wolfe’s is more personal and resonant than others that saw print.

Glenn: I’d be interested to hear how your perception of the books has been colored by the films. Most everyone I know started with the books, or watched the films without having ever read Tolkien (and have no interest in doing so). Have you found that the films have negatively affected your reading experience?

I’m in that seemingly rare group who likes and appreciates both on their own merits, though I do prefer the books.

Luke: I’ll guess we’ll just have to agree to disagree. I understand what you mean by Twilight’s success not being a barometer of quality, but I’d be willing to eat my hardbound copy of The Silmarillion if we ever see New Moon crack the top 100 novels of all time list in Time magazine. The difference here is that The Lord of the Rings is not only immensely popular, but also acclaimed by critics, studied by academics and scholars, and taught in schools.

Again, this doesn’t necessarily make The Lord of the Rings a great book, as many works that are studied and taught are anecdotally little read (Moby Dick and War and Peace, for example). But if you’re looking for yardsticks to measure the worth of a book, commercial and critical success have to be considered.

I also think you’re a bit off-base with calling LOTR too “bloated and unpublishable” for today’s market. I mean, George R.R. Martin’s immensely popular A Storm of Swords is approximately 900 pages. By way of comparison, the hardbound The Lord of the Rings I have sitting on my bookshelf checks in at 1,008 pages–all three “books” (Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King) combined. And a Storm of Swords is only one book in the Ice and Fire series, which is up to 4 books and counting.

I would submit that LOTR is positively in fighting trim compared to series like A Song of Ice and Fire and The Wheel of Time, and those have sold very, very well.

[…] a Black Gate post, an interesting essay by Gene Wolfe in defense of The Lord of the Rings’ underlying […]

Brian: The link to the best selling books list on Wikipedia held some other intriguing titles, including a number of works by Mao, which I would assume generally create a rather polarized opinion, either way. It seems likely that many of those titles also expressed huge explosions, followed by slow growth periods after that. I’m sure The Lord of the Rings has had steady growth, but it seems to have really bloomed early on, and then after the films. And based on the Twilight SAT Prep guides at Walmart, and the Twilight & Philosophy volume, I imagine that at least some people are finding something worth studying in it. I believe the Literature Majors capstone course here at MSU is looking at one of the Twilight books for the 400 level Dark Romanticism course.

By bloated I didn’t mean to imply just that it was long. As you said, War and Peace is huge, but it is justly a classic. When I said bloated, I meant that, at 1,008 pages (I can’t find my copy, so I hope you don’t mind my stealing your number), it was about 500 pages too long for the story it had to tell.

I hate to make this comparison, because Terry Brooks is another author who seems to polarize people, but his Sword of Shannara was a deliberate take on The Lord of the Rings, and covered the entire story in 600 or so pages. Yes, not as successful, largely because it attracted readers who read The Lord of the Rings and who, upon reading Brooks, realized that they had read this story before.

Everyone has read a novel that simply feels fattened out with excess filler, and I feel that most of LotR is just that: filler that doesn’t move the plot. Are there longer popular fantasy books? Certainly. Does that justify LotR’s length, when it could be much shorter? Not at all.

Might I add that the list is “All TIME 100 Novels,” in reference to TIME magazine, the list only selects books published since 1923. On a list that is truly the top 100 books of all time, I would certainly question the validty of placing Lord of the Rings upon it.

I suppose it will just have to be agreeing to disagree. I’m one of those weird few who just doesn’t get it 🙂

well luke i respect that opinion and understand where your coming from. Its largely a matter of preference. I think that all of the ‘extra’ twists and turns adds to the believability of the story. I mean when frodo leaves the shire in the first book its not a b-line for bree or even rivendell. Tom bombadil and the barrow wights do very little or nothing for the plot but i enjoyed those parts very much and would miss them if some editor took them out.

Brian, The movies have taken away from the experience of the books. Its been awhile since i’ve seen the movies. i saw Return 3 times when it came out, but i’ve only seen the others once. I know whats going to happen for the most part. For example i just read the part in the two towers when the Ents are heading towards Isengard there aren’t any big hints that make you think their just going to go crazy and destroy the place. When Aragorn and crew show up and see it destroyed practically that would have been an AH! moment for me, but that was taken away by the movies. As well as the part where gandalf ‘dies’ in Moria.

Glenn: For me it was less incidents like Tom Bombadil and the barrow wights, and more the excessive descriptors, the over-indulgence in unneccesary details. I could care less about the elven language, but it is force fed to me, things like that. The Lord of the Rings has always come across to me as Tolkien’s vehicle to place every bit of information he could about a world he made up, even if it hurt the story. He also, in my mind, introduced vast amounts of this information in clumsy ways, instead of integrating it into the plot in a more seamless fashion. I always had the impression that I would never find Middle Earth as cool as Tolkien did.

Is the straight to the climax method always best? No, I certainly don’t disagree with you there. In the hands of a capable writer, it can be a great vehicle to explore the story and its characters. However, it can also backfire, stalling the plot and crashing any thematic momentum. Thats how The Lord of the Rings happened for me. Too little plot strung on too many words, divorcing my attention after one too many divergences. Make them important to the plot, or get them out. That is my take at least. And I think that a lot of the fantasy series today that are far more bloated than Tolkien’s are a result of his influence in that regard.

Again, I am the odd man out here, so most people obviously find an appeal in the story and the world Tolkien has created. You can’t please all the people all the time, and I guess Tolkien just didn’t get me this time. Whether I liked it or not, The Lord of the Rings did a lot of good for the genre, and I won’t ever say otherwise. Even if it was far longer than necessary…*grumble*…:)

Don’t forget Michael Moorcock’s own attacks on Tolkien and the Lord of the Rings. Another author I like who decides to be a dillweed and take shots at a great author and a classic piece of fiction. Why can’t everyone agree to disagree?

On another note, I wonder what these authors-turned-critics think of the Silmarillion? I’m sure they have nothing good to say. I’m sure they’d be unoriginal and call it “boring” like all the others who don’t have the mettle to make it through that great work. Let’s see one of these guys write something with the same depth of mythology, intricacy, and pure unadulturated legendry!

I myself was bothered by Moorcock’s badmouthing Lord of the Rings called it escapism and things like that. I’ve bought some of Moorcock’s fantasy, but i haven’t read it yet. I don’t like it when anyone calls fantasy ‘escapism’. I’m sure there are people who label the Elric books as escapism…

[…] Wolfe’s lost road: Discovering an author’s personal essay on J.R.R. Tolkien [*1] […]

[…] themes were never far below the surface in his earlier work. In an essay on Tolkien titled “The Best Introduction to the Mountains,” Wolfe made explicit what was implicit in nearly all of his fiction: Domination and hierarchy are […]