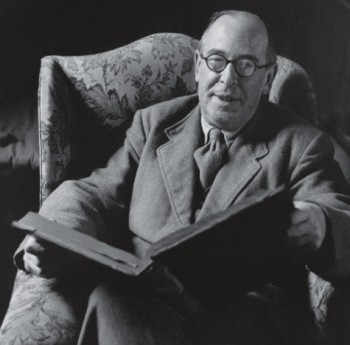

On Stories: Discovering a kindred spirit in C.S. Lewis

Though he’s best known as the author of the Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was also a prolific essayist and an ardent defender of fantasy literature. In addition to medieval studies (The Allegory of Love) and Christian apologetics (Mere Christianity), Lewis wrote several essays about the enduring appeal of mythopoeic stories, connecting fantasy’s remote, heroic past to its flowering in the early 20th century.

Though he’s best known as the author of the Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was also a prolific essayist and an ardent defender of fantasy literature. In addition to medieval studies (The Allegory of Love) and Christian apologetics (Mere Christianity), Lewis wrote several essays about the enduring appeal of mythopoeic stories, connecting fantasy’s remote, heroic past to its flowering in the early 20th century.

Lewis’ passion and erudition in the mythopoeic comes pouring through in On Stories and Other Essays on Literature, a collection of essays and reviews loosely tied around fantasy literature. Lewis’ overarching theme in On Stories is that the best mythopoeic/romance literature (which includes works like E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and H. Rider Haggard’s She) stacks up with the best mainstream literature, and thus deserves to be not only enjoyed, but studied and preserved (I can sense a lot of nodding heads around here, but keep in mind that Lewis wrote these essays in an age when it was heresy to compare fantasy fiction to “real” lit).

Fantasy literature is often perceived as simple because many of its authors shun modernist/humanist perspectives and instead opt for archetypal characters and stories told with bright splashes of color, set in mythic worlds that never were. But as Lewis forcefully and convincingly states in On Stories and Other Essays on Literature, surface simplicity should not be mistaken for shallowness. Mythopoeic authors simply work from a different aesthetic. In fact fantasy literature deals directly with the big issues: Life and death, the possibility of an afterlife, the necessity of sacrifice, and of the importance of moral and ethical behavior. And it engages with these issues better than most modern, popular novels, Lewis says, because it confronts the human condition on a stark stage, battle lines clearly drawn. “A great myth is relevant as long as the predicament of humanity lasts; as long as humanity lasts. It will always work, on those who can receive it, the same catharsis,” writes Lewis.

On Stories and Other Essays on Literature takes to task critics that dismiss fantasy outright, those that claim that stories that feature swords and sorcery or set in other worlds cannot possibly be taken seriously—and are thus for children and serve only to sate the childlike need for escapism. Such critics regard the novels of Henry James or Emily Bronte as serious literature while treating Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes or Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword with scorn and contempt.

On Stories and Other Essays on Literature takes to task critics that dismiss fantasy outright, those that claim that stories that feature swords and sorcery or set in other worlds cannot possibly be taken seriously—and are thus for children and serve only to sate the childlike need for escapism. Such critics regard the novels of Henry James or Emily Bronte as serious literature while treating Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes or Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword with scorn and contempt.

Lewis, a World War I veteran, viewed the world through a different (and I would argue ‘clearer’) lens. In On Stories he claims that heroic fantasy is simply too vital and vulgar for those readers and critics who see “real life” mirrored in the social and societal struggles of the restrained characters of Middlemarch or Daisy Miller.

“This hatred comes in part from a reluctance to meet Archetypes; it is an involuntary witness to their disquieting vitality. Partly, it springs from an uneasy awareness that the most ‘popular’ fiction, if it only embodies a real myth, is so very much more serious than what is generally called ‘serious’ literature. For it deals with the permanent and inevitable, whereas an hour’s shelling, or perhaps a ten-mile walk, or even a dose of salts, might annihilate many of the problems in which the characters of a refined and subtle novel are entangled.”

Despite its slim size (153 pages), On Stories and Other Essays On Literature overflows with quotable passages like the one above. For example, on the joys of re-reading:

“We do not enjoy a story fully at the first reading. Not till the curiosity, the sheer narrative lust, has been given its sop and laid asleep, are we at leisure to savor the real beauties. Till then, it is like wasting great wine on a ravenous natural thirst which merely wants cold wetness.”

On the power of mythic stories:

“The value of the myth is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by ‘the veil of familiarity.’”

And on the ridiculous notion that great literature can become “dated”:

“The truth is that the whole criticism which turns on dates and periods, as if age-groups were the proper classification of readers, is confused and even vulgar… It is vulgar because it appeals to the desire to be up to date: a desire only fit for dressmakers.”

Lewis’ succinct insights on Tolkien in On Stories have arguably never been bettered, save perhaps by Tom Shippey. For example, Lewis compares the bookstore arrival of The Fellowship of the Ring to “lightning from a clear sky” and its moral compass fusion of Northern paganism with Christianity as “hammerstrokes with compassion.” Writes Lewis of The Lord the Rings: “If we insist on asking for the moral of the story, that is its moral: a recall from facile optimism and willing pessimism alike, to that hard, yet not quite desperate, insight into Man’s unchanging predicament by which heroic ages have lived.”

Though Lewis also loves fantasy for the sake of pure story, he forces us in On Stories to examine the reasons why its best works resonate. By placing works like the Faerie Queene, Beowulf, and The Iliad in a great chain of mythic literature alongside his 20th century contemporaries, Lewis effectively makes the case that fantasy stories have always been with us, enlarging our experiences and sensations “like certain rare dreams.” For that reason alone On Stories is worth the time of any serious fan of fantasy literature.