Why We Keep Weaving These Webs

My buddy Gabe and I, when we first met almost two decades ago, we knew — man, we knew our stuff was better (or was going to be better) than just about anything out there. It was the haughty arrogance of youth and ego, plus the fact that we just hadn’t read nearly as much of what was out there as we have now.

My buddy Gabe and I, when we first met almost two decades ago, we knew — man, we knew our stuff was better (or was going to be better) than just about anything out there. It was the haughty arrogance of youth and ego, plus the fact that we just hadn’t read nearly as much of what was out there as we have now.

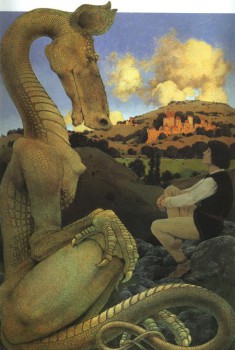

Consider, too, the impressions we’d formed in our teen years of what was most prevalent in the various popular-media streams: the (much smaller) fantasy book aisle was dominated by Terry Brooks and many lesser Tolkien imitators churning out derivative high-fantasy formula. Comics were still stuck in stunted-development adolescence, just on the cusp of the revolution when writers like Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman would kick that medium in its juvenile ass. Films were mostly sci-fi knockoffs of Star Wars or B-grade fantasy with special-effects budgets so meager they wouldn’t fund a single episode of a typical SyFy TV show. And television animated fantasy didn’t aspire much beyond Hanna-Barbera cartoons and He-Man.

In short, based on that narrow and selective assessment, any cocksure young tale-weaver could survey that crop and think, “I can do better than that.” But we weren’t the only Gen Xers who nursed such thoughts. Many others could also do better, and they have.

With our generation, speculative fiction has entered into what seems a golden age, borne out in all those mediums — books, comics, film, television (and add another medium that was just emerging from its nascent stages when we entered the fray: video games). Individuals with tastes and perceptions kindred to our own are drawing on the best of the past like never before, fusing with modern sensibilities what they mine from those rich veins to create some of the finest work the genre has ever seen.

And they’ve infiltrated all levels of the creative business. When I watch old He-Man and She-Ra reruns with my kids, I get the impression that those writers were just lazily phoning it in for a paycheck and couldn’t give a damn about the words they were putting to paper or the stories they were slapping together. Contrast that with the short-lived He-Man relaunch (2002-2004). It wasn’t a stand-out show by any means, but it was heads above virtually anything that cynically aired in the early ‘80s to sell us toys from Mattel and Kenner and Hasbro. Yeah, that particular corner of the market still exists to sell toys — to our kids and grandkids now — but the people who are creating the product were kids like Gabe and me, who thought, “Man, if I could have a job writing that show, I would make it so cool.” And they do have those jobs, and they are.

So where does that leave us, web-weavers in a surfeit of webs?