Alien Eggs, a Diligent Salesman, and a Robot Psychiatrist: Three Stories by Idris Seabright

|

|

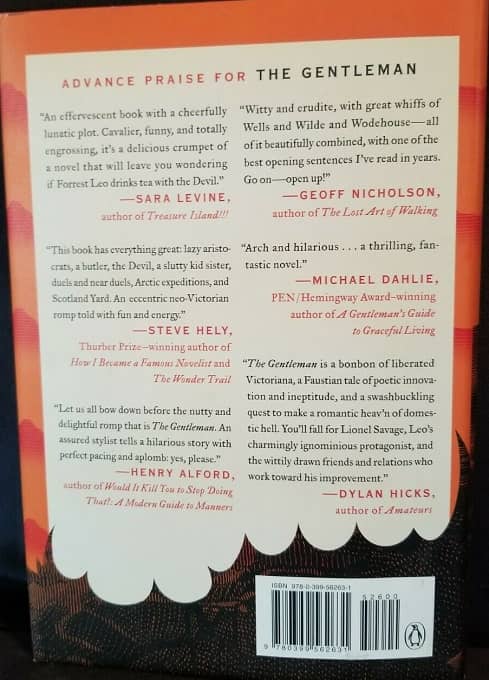

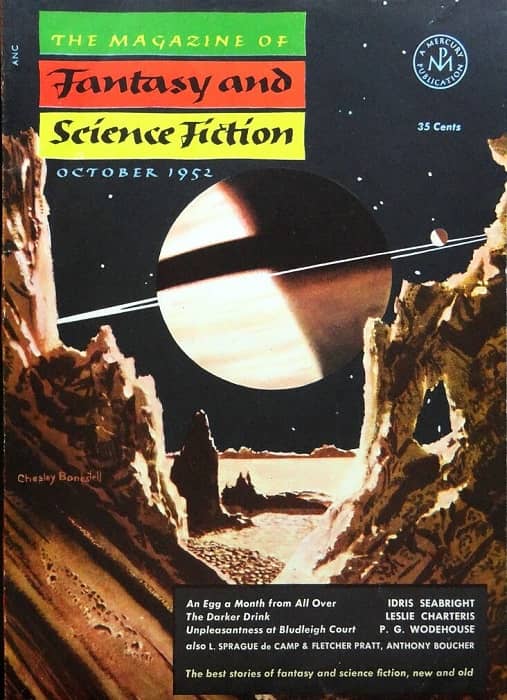

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, October 1952. Cover art by Chesley Bonestell

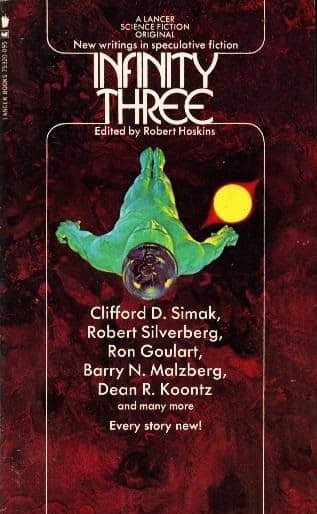

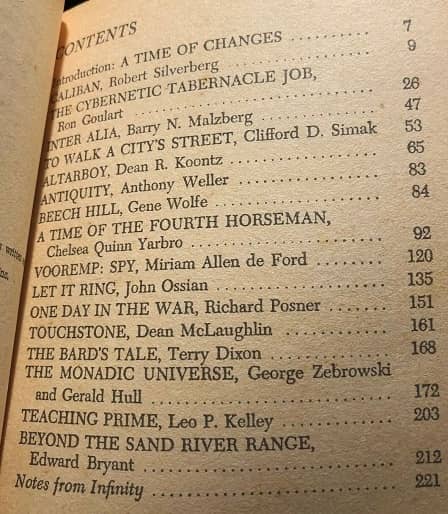

For my next look at older stories which I think are both good, and worth looking at closely, I’m covering three stories by one “Idris Seabright.” “Who she?” you might ask, or even “Who he?,” as the currently most famous Idris in the world is a man. “Idris Seabright” was a pseudonym used by the SF writer Margaret St. Clair for about 20 stories, all in the ‘50s. The “Seabright” name was used almost exclusively for stories published in F&SF – the single exception is one of her most famous stories, “Short in the Chest,” which appeared in Fantastic Universe. (The ISFDB credits a curious Seabright outlier, a story published in Spanish only, very late in St. Clair’s life, in 1991. I feel this must be a translation of an earlier Seabright story though I’m not sure which one. The story is called “La Estrana Tienda,” which means “The Strange Store” or perhaps “The Mysterious Shop.”)

Margaret St. Clair (1911-1995) was one of the more noticeable early women writers of SF, but somehow her profile was a bit lower than those of C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, and Andre Norton. I guess I’d say that those writers did just a bit more, and were just a bit better (taken as a whole) than her, but it does seem that she’s not quite as well remembered as perhaps she deserves. One contributing factor is probably, however, that many of her best and most interesting stories were as by “Idris Seabright.” In addition, those of her novels I’ve read were less successful than her short fiction. Her career in SF stretched from 1946 to 1981. Her husband, Eric St. Clair, was also a writer (of children’s books), and the two became Wiccans more or less when the Wiccan movement started.