Fantasia 2017, Day 1: The Bizarre Adventure Begins (JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond Is Unbreakable)

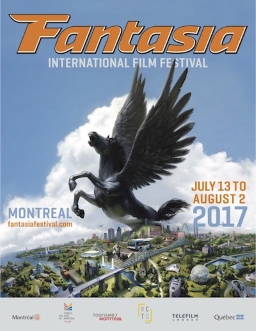

The body has a memory, memory activated by the time of year and the weather and the repetition of physical activity. Every year now as summer passes its midpoint, walking through Montreal evokes for me a sense of wonder and anticipation: a physical remembrance of the Fantasia International Film Festival. I’ve covered Montreal’s genre film festival for Black Gate the last three years, walking downtown during the days of the festival and then walking back at night marveling at the things I’ve seen. Last Thursday for a fourth year I set out for the Fantasia theatres at Concordia University’s downtown campus; and so here is the first installment of my Fantasia diary for 2017.

The body has a memory, memory activated by the time of year and the weather and the repetition of physical activity. Every year now as summer passes its midpoint, walking through Montreal evokes for me a sense of wonder and anticipation: a physical remembrance of the Fantasia International Film Festival. I’ve covered Montreal’s genre film festival for Black Gate the last three years, walking downtown during the days of the festival and then walking back at night marveling at the things I’ve seen. Last Thursday for a fourth year I set out for the Fantasia theatres at Concordia University’s downtown campus; and so here is the first installment of my Fantasia diary for 2017.

As always, I’m looking forward over the coming weeks to things I’ve heard of and things I’ve never heard of. I’m trying to figure out what movies I’ll have to pass on seeing in order to watch other movies scheduled against them, and then what movies I’ll be able to see on a computer monitor in the Fantasia screening room. This year the recipients of the festival’s Lifetime Achievement Awards are a little outside my immediate areas of interest — B-movie auteur Larry Cohen, luchador and movie star Mil Máscaras, and Cüneyt Arkin, star of over 300 Turkish films including The Man Who Saved the World (Dünyayi Kurtaran Adam, also known as “Turkish Star Wars”). But who knows if I’ll find myself sitting in on a screening of one or more of their varied works?

This year I began my Fantasia experience on the festival’s first night, Thursday July 13, with a viewing of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond is Unbreakable. I arrived early, reaching the Hall Theatre at 8:30 PM for a 9:45 screening, and found a line-up of ticketholders already stretching a good 200 feet. The movie’s directed by Takashi Miike, a winner of last year’s Lifetime Achievement Award, with a script by Itaru Era based on the long-running manga by Hirohiko Araki. I happened to watch this showing in the company of the redoubtable Dave Harris of Pieuvre.ca; neither of us had any experience of the manga, but after the movie we were able to speak briefly with some friends of Dave’s who were fans of the comics. “11 out of 10,” said one, while another said that the movie was so faithful it replicated specific panels on the screen. So: if you’re a fan of the source material, you will like this movie. What about those who aren’t?

At the Emerald City Comicon in early March, Image Comics announced that starting in August they’d be publishing writer/artist Matt Wagner’s Mage: The Hero Denied, a 15-issue series with a half-length 0 issue and a double-sized conclusion. Hero Denied will be the final part of a trilogy Wagner began over thirty years ago, and I want to prepare for that last installment by looking back here at the first parts of the saga. The Mage books are two of the finest works of a great comics talent, urban fantasies mixing excellent action storytelling, a mastery of plot beats, and a sense of the mythic into gripping stories — and stories with a semi-autobiographical slant, no less.

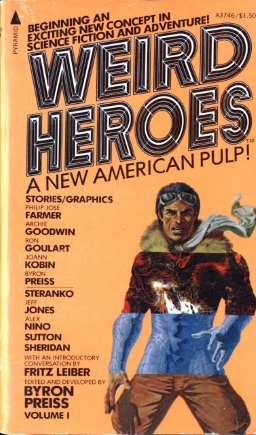

At the Emerald City Comicon in early March, Image Comics announced that starting in August they’d be publishing writer/artist Matt Wagner’s Mage: The Hero Denied, a 15-issue series with a half-length 0 issue and a double-sized conclusion. Hero Denied will be the final part of a trilogy Wagner began over thirty years ago, and I want to prepare for that last installment by looking back here at the first parts of the saga. The Mage books are two of the finest works of a great comics talent, urban fantasies mixing excellent action storytelling, a mastery of plot beats, and a sense of the mythic into gripping stories — and stories with a semi-autobiographical slant, no less. Weird Heroes was a series of eight books put out by Byron Preiss Visual Publications from 1975 through 1977, a copiously-illustrated mix of novels and short stories that aimed at creating a new kind of pulp fiction with new kinds of pulp heroes. The series had a specific set of ideals for its heroes, linked with an appreciative but not uncritical love of pulp fiction from the 1920s through 40s. Well-known creators from comics and science fiction contributed to the books, and one character would spawn a six-volume series of his own. And yet Preiss’ long-term plans for Weird Heroes were cut short with the eighth volume, and today it’s hard to find much discussion of the books online (though

Weird Heroes was a series of eight books put out by Byron Preiss Visual Publications from 1975 through 1977, a copiously-illustrated mix of novels and short stories that aimed at creating a new kind of pulp fiction with new kinds of pulp heroes. The series had a specific set of ideals for its heroes, linked with an appreciative but not uncritical love of pulp fiction from the 1920s through 40s. Well-known creators from comics and science fiction contributed to the books, and one character would spawn a six-volume series of his own. And yet Preiss’ long-term plans for Weird Heroes were cut short with the eighth volume, and today it’s hard to find much discussion of the books online (though

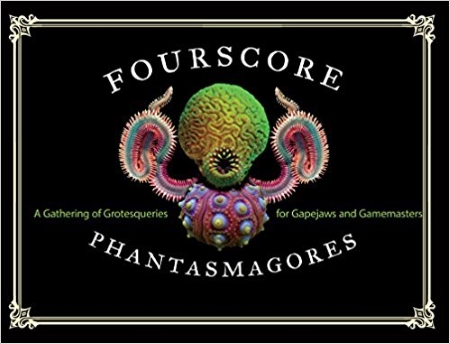

There’s a paradox in the nature of a dictionary of monsters. The medieval bestiaries at least claimed to be compendia of actual knowledge. But books like Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero’s Book of Imaginary Beings (Manual de zoología fantástica) and perhaps even Katharine Briggs’ Dictionary of Fairies are only superficially rational collections of information. Though alphabetised and cross-referenced, the logical framework’s a way of presenting wild fantasy and dream: basilisks and baldanders, brownies and banshees, sylphs and sphinxes. The Monster Manual, and the role-playing handbooks it inspired, take this contradiction to a new level — detailed statistics for each creature described along with the avowed intent of inspiring new stories featuring the legendary or imaginary entities. Quantified, numerically precise, the monsters in these enchiridia still crack open the inside of the head, driving readers to imagine worlds big enough to hold dungeon-dwellers and dragons. Rupert Bottenberg’s Fourscore Phantasmagores is the newest volume of these wonders for gamers and monster-lovers of all stripes, presenting, as it says on the cover, “A Gathering of Grotequeries for Gapejaws and Gamemasters.” And, conscious of its predecessors, the book’s a rich source of inspiration; a grimoire seeding new myths.

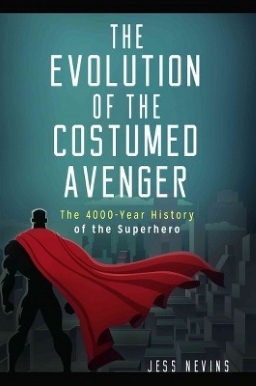

There’s a paradox in the nature of a dictionary of monsters. The medieval bestiaries at least claimed to be compendia of actual knowledge. But books like Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero’s Book of Imaginary Beings (Manual de zoología fantástica) and perhaps even Katharine Briggs’ Dictionary of Fairies are only superficially rational collections of information. Though alphabetised and cross-referenced, the logical framework’s a way of presenting wild fantasy and dream: basilisks and baldanders, brownies and banshees, sylphs and sphinxes. The Monster Manual, and the role-playing handbooks it inspired, take this contradiction to a new level — detailed statistics for each creature described along with the avowed intent of inspiring new stories featuring the legendary or imaginary entities. Quantified, numerically precise, the monsters in these enchiridia still crack open the inside of the head, driving readers to imagine worlds big enough to hold dungeon-dwellers and dragons. Rupert Bottenberg’s Fourscore Phantasmagores is the newest volume of these wonders for gamers and monster-lovers of all stripes, presenting, as it says on the cover, “A Gathering of Grotequeries for Gapejaws and Gamemasters.” And, conscious of its predecessors, the book’s a rich source of inspiration; a grimoire seeding new myths. Though he’s written short stories and three self-published novels, Jess Nevins is likely best known as an excavator of fantastic fictions past: an archaeologist digging through the strata of the prose of bygone years, unearthing now pieces of story and now blackened ashes of some once-thriving genre long since consumed and built over by its lineal successor. Across annotated guides (three to Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, one to Bill Willingham and Mark Buckingham’s Fables) and self-published encyclopedias (of Pulps and of Golden Age Superheroes with Pulp Heroes soon to come, as well as 2005’s Monkeybrain-published Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana) Nevins has reassembled old pieces of fantastika, indicating direct influences on modern writing and establishing directories of almost-forgotten story. He’s one of the people broadening the history of genre, in his books, and in articles such as

Though he’s written short stories and three self-published novels, Jess Nevins is likely best known as an excavator of fantastic fictions past: an archaeologist digging through the strata of the prose of bygone years, unearthing now pieces of story and now blackened ashes of some once-thriving genre long since consumed and built over by its lineal successor. Across annotated guides (three to Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, one to Bill Willingham and Mark Buckingham’s Fables) and self-published encyclopedias (of Pulps and of Golden Age Superheroes with Pulp Heroes soon to come, as well as 2005’s Monkeybrain-published Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana) Nevins has reassembled old pieces of fantastika, indicating direct influences on modern writing and establishing directories of almost-forgotten story. He’s one of the people broadening the history of genre, in his books, and in articles such as  Having finally posted reviews of all the movies I saw at the 2016 Fantasia International Film Festival, I want by way of conclusion to think about what I’ve learned. I don’t just mean about film, or about the film industry. But about genre, and what genre does, and how it works on film.

Having finally posted reviews of all the movies I saw at the 2016 Fantasia International Film Festival, I want by way of conclusion to think about what I’ve learned. I don’t just mean about film, or about the film industry. But about genre, and what genre does, and how it works on film. Wednesday, August 3, was the last day of the Fantasia International Film Festival. Three full weeks of genre films would wrap up here, and I was looking forward to the three last films of the year. The day would begin with the Chinese martial-arts film Judge Archer (Jianshi liu baiyuan). After that came the independent American movie If There’s a Hell Below, promising a paranoid thriller about whistleblowers and government surveillance. Finally came a movie I’d been eagerly anticipating since the start of the festival, the Polish science-fictional classic from 1977 On the Silver Globe (Na srebrnym globie), a space opera about colonization and war on an alien planet. All three were rewarding, and all three were pleasantly (and increasingly) elliptical.

Wednesday, August 3, was the last day of the Fantasia International Film Festival. Three full weeks of genre films would wrap up here, and I was looking forward to the three last films of the year. The day would begin with the Chinese martial-arts film Judge Archer (Jianshi liu baiyuan). After that came the independent American movie If There’s a Hell Below, promising a paranoid thriller about whistleblowers and government surveillance. Finally came a movie I’d been eagerly anticipating since the start of the festival, the Polish science-fictional classic from 1977 On the Silver Globe (Na srebrnym globie), a space opera about colonization and war on an alien planet. All three were rewarding, and all three were pleasantly (and increasingly) elliptical. Tuesday, August 2, was the next-to-last day of the 2016 Fantasia festival. I had two movies lined up. First would come The Arbalest, at the De Sève Theatre: a period fantasy about a man who made an addictive puzzle in a slightly alternate 1970s. That would be followed by The Piper (Sonmin), a Korean film that reimagined the Pied Piper story as set in a postwar Korean village. Both looked promising. One delivered on that promise.

Tuesday, August 2, was the next-to-last day of the 2016 Fantasia festival. I had two movies lined up. First would come The Arbalest, at the De Sève Theatre: a period fantasy about a man who made an addictive puzzle in a slightly alternate 1970s. That would be followed by The Piper (Sonmin), a Korean film that reimagined the Pied Piper story as set in a postwar Korean village. Both looked promising. One delivered on that promise. By Monday, August 1, the end of the 2016 Fantasia Film Festival was in sight. Two more days, and it’d be over for another year. Bearing that in mind I was determined to pass by the Festival’s screening room and catch up with some films I’d missed earlier in the festival. First, though, I was headed to the De Séve Theatre for a showing of the American-Polish science-fiction movie Embers, about a world struck by a plague of forgetting. After that I’d go to the screening room, where I’d watch the French absurdist comedy L’Élan and the Mexican horror-fantasy We Are the Flesh (Tenemos la carne).

By Monday, August 1, the end of the 2016 Fantasia Film Festival was in sight. Two more days, and it’d be over for another year. Bearing that in mind I was determined to pass by the Festival’s screening room and catch up with some films I’d missed earlier in the festival. First, though, I was headed to the De Séve Theatre for a showing of the American-Polish science-fiction movie Embers, about a world struck by a plague of forgetting. After that I’d go to the screening room, where I’d watch the French absurdist comedy L’Élan and the Mexican horror-fantasy We Are the Flesh (Tenemos la carne).