Old New Pulp: Byron Preiss’ Weird Heroes

Weird Heroes was a series of eight books put out by Byron Preiss Visual Publications from 1975 through 1977, a copiously-illustrated mix of novels and short stories that aimed at creating a new kind of pulp fiction with new kinds of pulp heroes. The series had a specific set of ideals for its heroes, linked with an appreciative but not uncritical love of pulp fiction from the 1920s through 40s. Well-known creators from comics and science fiction contributed to the books, and one character would spawn a six-volume series of his own. And yet Preiss’ long-term plans for Weird Heroes were cut short with the eighth volume, and today it’s hard to find much discussion of the books online (though they’re well-remembered when they are discussed). That absence is a little surprising, as a whole new generation of writers has come along with an interest in creating new pulps. Now that we’re separated from Weird Heroes by about the amount of time it was separated from the original pulps, it’s well worth a look back at its truncated run.

Weird Heroes was a series of eight books put out by Byron Preiss Visual Publications from 1975 through 1977, a copiously-illustrated mix of novels and short stories that aimed at creating a new kind of pulp fiction with new kinds of pulp heroes. The series had a specific set of ideals for its heroes, linked with an appreciative but not uncritical love of pulp fiction from the 1920s through 40s. Well-known creators from comics and science fiction contributed to the books, and one character would spawn a six-volume series of his own. And yet Preiss’ long-term plans for Weird Heroes were cut short with the eighth volume, and today it’s hard to find much discussion of the books online (though they’re well-remembered when they are discussed). That absence is a little surprising, as a whole new generation of writers has come along with an interest in creating new pulps. Now that we’re separated from Weird Heroes by about the amount of time it was separated from the original pulps, it’s well worth a look back at its truncated run.

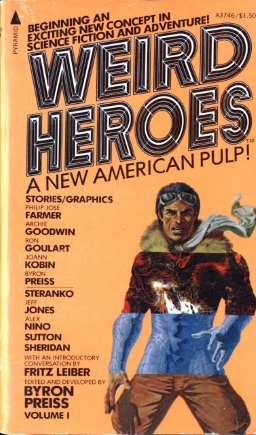

Editor Byron Preiss was only 21 years old when he founded Byron Preiss Visual Publications in 1974, and the company began putting out two series of illustrated paperbacks the next year, Weird Heroes and Fiction Illustrated (which ran for four volumes with a fifth issued under a different name). Both were packaged by BPVP to be published by Pyramid Books. Weird Heroes started its run with two anthologies of short fiction that, according to Preiss’ introductions to both books, were conceived as a single volume but divided up due to length constraints. Over the course of the series’ run, it published work by Archie Goodwin, Steve Englehart, Harlan Ellison, and Michael Moorcock, alongside art by Jim Steranko, Alex Niño, Neal Adams, and P. Craig Russell.

In the editorial matter within the first book, Preiss laid out what he hoped to do with the series. Across a general introduction, a historical discussion of “old American pulp,” and an interview with Fritz Leiber later on in the book, Preiss articulated a specific sense of what old pulps did well, what they did poorly, what he wanted to take from them, and what he wanted to improve on. He also wrote about presenting an alternative to the heroes that had emerged up to that point in 1970s popular culture. Broadly, he wanted to recapture the storytelling thrills of pulp fiction and its sense of wonder, while avoiding its misogyny and racism — and unlike what he saw in both the pulps and much 1970s hero fiction, he wanted to find a way to resolve stories and conflicts without the use of violence and murder.

It’s worth looking closely at what Preiss wrote as a way to judge the series he’d eventually create. In his Introduction he said (boldface in the original:

Weird Heroes is a collective effort to give back to heroic fiction its thrilling sense of adventure and entertainment — the heartbeat of the old pulps.

Asking why heroes were “needed,” he argued that pulp heroes “… were more than individuals doing some outstanding activity in the name of some cause. They were symbols — and that’s what all America’s lasting heroes are: symbols.” They endured “when our supposedly ‘real’ heroes — elected officials, peacekeeping world bodies, chiefs of state, and public administrators — are too frequently being revealed as fraudulent, incompetent, or unscrupulous,” because

…those characters represent basic hopes and dreams which people continue to share. They represent peace, justice, tenacity, and freedom.

For this, they are “needed.” It is a healthy and important indicator that these heroes are present. It is less than healthy to see the parade of many of the new heroes: the Destructor, the Baroness, the Penetrator, the Eliminator. Death. Violence. Symbols that “justice” can be bought with the muzzle of a gun.

So we return to our new heroes. They are an outcry. A statement of “No! — that’s not the only way things can be done.” Weird Heroes is one alternative to other new heroes. Our characters are symbolic of different ideals, or at least of different ways to reach the same ideals.

At the same time, Preiss didn’t think the pulps were perfect. Near the close of the introduction he reflected:

A central message of some of the old pulps and many of the new paperback adventurers is: Violence can solve your problems. A central message of this new American pulp is Respect life and enjoy it.

If there is a common ground between this new American pulp and the old pulps, it is a feeling of enthusiasm. A feeling of fresh creative effort and a hope that what we are doing is exciting.

Preiss elaborated on both his appreciation and his critique of the pulps in “What Is an Old American Pulp?”, a historical essay following the introduction. “For the poor, the young orphan, and the lonely soldier abroad, the pulps were a world of epic adventure where the end was always certain and justice would always triumph,” he writes, and: “For the older reader, the pulps held the lure of excitement and tight writing.” But: “The old American pulps were filled with adventure, spectacular, ambitious plots, and taut dramatic stories. At times, they were also filled with hack writing, racism, sexism, and titillation …” Still, what he takes away from the pulps is positive: “To new readers, an old pulp is wonderment, fun, and adventure rolled into one book.” So “… If there’s anything of the old pulps we want to retain, it’s that feeling of wonder — and entertainment.”

What he wants to do differently comes out again in an interview with Frtiz Leiber. In the course of the discussion Preiss says “I consider it so important to move beyond the basic hero vs. villain confrontation in which violence plays a resolving role. There has to be more. There is more.” He goes on: “In putting together this book, I was very conscious of the authors’ freedom to write what he or she wants to write, but at the same time I felt strongly about the need to reach higher, past the old violent heroic molds to something new. What that ‘something’ is can be witnessed in many of the stories in the book.” So: “The pulps merit respect for their ability to evoke atmosphere, excitement, and a feeling of epic adventure. Weird Heroes aspires to entertain the reader, but it does so with a conscious effort to innovate. The result, hopefully, will be new heroes with a strong respect for human life.”

What he wants to do differently comes out again in an interview with Frtiz Leiber. In the course of the discussion Preiss says “I consider it so important to move beyond the basic hero vs. villain confrontation in which violence plays a resolving role. There has to be more. There is more.” He goes on: “In putting together this book, I was very conscious of the authors’ freedom to write what he or she wants to write, but at the same time I felt strongly about the need to reach higher, past the old violent heroic molds to something new. What that ‘something’ is can be witnessed in many of the stories in the book.” So: “The pulps merit respect for their ability to evoke atmosphere, excitement, and a feeling of epic adventure. Weird Heroes aspires to entertain the reader, but it does so with a conscious effort to innovate. The result, hopefully, will be new heroes with a strong respect for human life.”

This is a strong editorial stance. How did it play out? Did the eight books he put together match what he said he was looking to do? The best way to answer these questions, I think, is to go through the books one by one, story by story. Which is also worth doing given the calibre of talent involved in the books, not just in the writing but in the illustrations throughout the books. Note that most of the stories have introductions by Preiss and afterwords by the writers.

Things kick off with “Quest of the Gypsy,” by Ron Goulart, with illustrations by Alex Niño. In a semi-post-apocalyptic 2033, a man wakes up from decades of suspended animation with no memories and strange powers; he adventures around an amusingly stereotypical France and England, and realises he’s caught in a long-term game with an unknown and possibly long-dead opponent. Ron Goulart was already a veteran neo-pulp writer by the mid-70s, and has since gone on to write fiction starring everyone from the Incredible Hulk to Groucho Marx. This story’s tightly-written and imaginative, entirely satisfying except for the hero’s name (these days, at least) being frequently considered an ethnic slur. Following that comes “Stalker,” by veteran comics writer Archie Goodwin, illustrated by underground cartoonist and Gilbert Shelton collaborator Dave Sheridan. Adam Stalker’s a Vietnam vet who ran afoul of a sinister group of oil tycoons and now lives in a trailer park, trying to find constructive outlets for his violent impulses — when a private investigator turns up at his door with a case that might give him a chance at justice. It’s a straight-ahead action story, competent and frequently clever, even if the prose isn’t especially engaging.

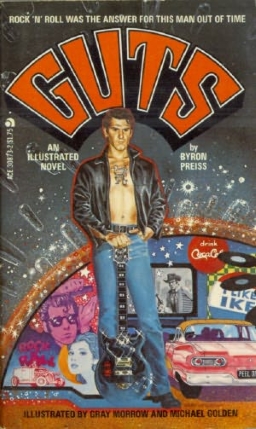

Byron Preiss’s own story “Guts,” illustrated by comics legend Jim Steranko, turns out to be one of the best stories of the book and indeed of the series as a whole. Written primarily in odd dialogue and sentence fragments, it’s the story of a future time-travelling agent trained to blend in to the 1950s while seeking some mislaid “radiofrenetic” material; stuck by accident in the 1970s, he becomes Guts, the cosmic greaser. A clever story blending characterisation with a series of wild ideas, it works in its own right and also feels like the origin of something more — and indeed Preiss would write a novel about the character a few years later.

Byron Preiss’s own story “Guts,” illustrated by comics legend Jim Steranko, turns out to be one of the best stories of the book and indeed of the series as a whole. Written primarily in odd dialogue and sentence fragments, it’s the story of a future time-travelling agent trained to blend in to the 1950s while seeking some mislaid “radiofrenetic” material; stuck by accident in the 1970s, he becomes Guts, the cosmic greaser. A clever story blending characterisation with a series of wild ideas, it works in its own right and also feels like the origin of something more — and indeed Preiss would write a novel about the character a few years later.

Joann Kobin’s “Rose in the Sunshine State,” illustrated by Jeff Jones, follows. It’s perhaps the most offbeat story in the series, a realistic tale about an elderly woman who learns to be a hero by helping her friends and taking part in community activism. Or, simply, by being a good person. It’s a nice piece of prose, and effectively broadens the idea of what a ‘hero’ is or can be. It’s followed by “Minstrel of Lankhmar,” the interview with Fritz Leiber (accompanied by an uncredited but stunning drawing). Leiber taks about his experience with the pulps in an engagingly pragmatic way. He was a professional writer, and the pulps were his market, for all the nostalgia they now engender. It’s a nice interview, in the course of which Leiber identifies as a feminist (“On the whole, I think I’ve always been quite a bit of a feminist”) and implicitly as a socialist (describing socialism and democracy as “good ideas to my mind”). He also challenges the worldview of much heroic fiction, arguing against breaking the world down into good guys and bad guys while also noting that doing so can be a helpful emotional release within an individual imagination.

The last story in the book is from Philip José Farmer, with drawings by Tom Sutton: “Greatheart Silver in Showdown at Shootout.” It’s the story of Greatheart Silver, a one-legged former airship captain who, persecuted by his girlfriend’s father, becomes a private eye. Mentored by a man who might be The Shadow in his dotage, he uses gadgets built into his prosthetic leg to help him in his adventures, while receiving visions of danger from the ghosts of his ancestors — who include Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson. It builds up to a conclusion in which geriatric pulp heroes and villains have a massive crossover and showdown. This all sounds like it should be great fun, but Farmer’s writing it as a humour piece, and his prose to my mind doesn’t have the inventiveness or sharpness of timing to pull it off. Most interesting, perhaps, is the afterword in which Farmer acknowledges that he wrote the showdown of senescent heroes as a kind of therapy: “When I kill them off, I am in a sense killing myself so I can be reborn. … I love them, but my ardor may be keeping me from going on to more ‘mature’ writing.”

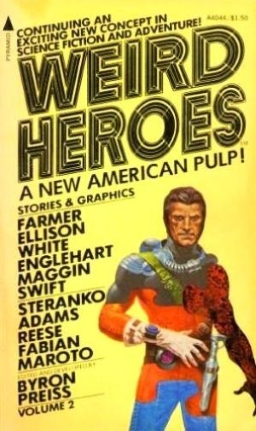

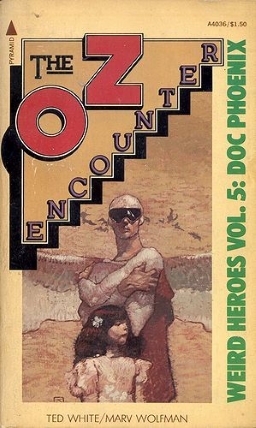

The second book opens with a story by Ted White, “Doc Phoenix.” Illustrated by Stephen Fabian, it’s a fine adventure about a heroic doctor-scientist who cures the psychological problems of his patients by physically entering their dreams. It’s tersely written, but Doc Phoenix himself is a bit too much of a knockoff of Doc Savage, with his omnicompetence and group of hangers-on. As well, there’s something disturbing in a love interest who, while specifically stated to be 28, is also specifically stated to look between 12 and 15. Next comes a story by Harlan Ellison illustrated by Neal Adams: “Cordwainer Bird in ‘The New York Review of Bird’” describes the heroic adventures of Ellison’s pseudonym Cordwainer Bird, and how Bird strikes back at the nefarious New York Literary Establishment on behalf of neglected writers everywhere. It’s a slight story, but Ellison’s verbal dexterity carries it off. It’s similar to, and indeed crosses over with, Farmer’s Greatheart Silver; Ellison’s prose is much better, but the connection strikes me as deriving from the most strained aspects of both stories. I don’t find anything inherently funny in the idea of a pulp adventurer in his 80s, though admittedly that may be a function of having seen the idea done better in the decades since Weird Heroes. (Compare the Andy Helfer–Kyle Baker Shadow comics for DC, if you like.)

The second book opens with a story by Ted White, “Doc Phoenix.” Illustrated by Stephen Fabian, it’s a fine adventure about a heroic doctor-scientist who cures the psychological problems of his patients by physically entering their dreams. It’s tersely written, but Doc Phoenix himself is a bit too much of a knockoff of Doc Savage, with his omnicompetence and group of hangers-on. As well, there’s something disturbing in a love interest who, while specifically stated to be 28, is also specifically stated to look between 12 and 15. Next comes a story by Harlan Ellison illustrated by Neal Adams: “Cordwainer Bird in ‘The New York Review of Bird’” describes the heroic adventures of Ellison’s pseudonym Cordwainer Bird, and how Bird strikes back at the nefarious New York Literary Establishment on behalf of neglected writers everywhere. It’s a slight story, but Ellison’s verbal dexterity carries it off. It’s similar to, and indeed crosses over with, Farmer’s Greatheart Silver; Ellison’s prose is much better, but the connection strikes me as deriving from the most strained aspects of both stories. I don’t find anything inherently funny in the idea of a pulp adventurer in his 80s, though admittedly that may be a function of having seen the idea done better in the decades since Weird Heroes. (Compare the Andy Helfer–Kyle Baker Shadow comics for DC, if you like.)

Charlie Swift’s “The Camden Kid” is another humour story, illustrated very nicely by Jim Steranko in a style reminsicent of Jack Kirby’s Western comics. Unfortunately, while the idea of a twentieth-century gunslinger from New Jersey coming to a town stuck in the 1870s is a good one, Swift’s writing is too leaden to work. It’s followed by “Viva,” by Stephen Englehart, who was usually credited as ‘Steve’ in his comics work — which had already involved major runs on books like Doctor Strange, Captain America, The Avengers, and Detective Comics at the time of Weird Heroes’ publication. Illustrated by Esteban Maroto, “Viva” is at least engagingly unpredictable. Viva’s a Puerto Rican prostitute who falls afoul of organised crime and tries to escape by plane only for the plane to crash at sea; saved from drowning by a mad scientist with an artificially-created body, Viva escapes again onto his jungle island and must find way to thwart his lustful pursuit. On the one hand, it’s difficult not to think about Preiss’ condemnation of sexism and titillation while reading this story, as Viva sends the first part of the story nude (faithfully depicted in one of the illustrations) and the last part of the story trying not to be raped. On the other hand, if occasionally clunky, the story also has the mad febrile energy that’s characteristic of much of the best pulp writing.

(Having read a fair amount of Englehart’s comics work over the years, I’ll also note that the conclusion of this story presages a notorious scene in his later run on West Coast Avengers. Here, Viva fights a would-be rapist who collapses over a cliff edge, hanging on by his fingers. She finds herself driven to preserve life, and saves him, in part, though he’s clearly left unable to threaten her further. Later, Englehart would write a very similar scene, in which a timelost heroine deliberately lets her rapist fall to his death over a cliff edge. The scene’s since been retconned, but in the context of Englehart’s work the parallel’s obvious. I’m not sure what to make of it, if anything, but there it is.)

Another comics writer, Elliot Maggin, provides the next story, “SPV 166, The Underground Express,” illustrated by Ralph Reese and Paul Kirchner. Written in a quasi-screenplay format, it follows three women ex-cons who’ve become agents of the New York City Police Department and solve fantastic crimes while operating from their own high-tech subway car. It’s an engaging set-up, the characters come across well, and the caper to hand is engagingly complex. It’s vaguely like a more wildly inventive Charlie’s Angels, which first aired a few months after the story was originally set to be published — except, if the characters here aren’t especially deep, they’re at least flat in the best heroic tradition, with an engaging vitality, competence, and agency to them.

Another comics writer, Elliot Maggin, provides the next story, “SPV 166, The Underground Express,” illustrated by Ralph Reese and Paul Kirchner. Written in a quasi-screenplay format, it follows three women ex-cons who’ve become agents of the New York City Police Department and solve fantastic crimes while operating from their own high-tech subway car. It’s an engaging set-up, the characters come across well, and the caper to hand is engagingly complex. It’s vaguely like a more wildly inventive Charlie’s Angels, which first aired a few months after the story was originally set to be published — except, if the characters here aren’t especially deep, they’re at least flat in the best heroic tradition, with an engaging vitality, competence, and agency to them.

Another of Farmer’s Greatheart Silver stories follows, again illustrated by Tom Sutton. I don’t care for it any more than the first one, though the often-underrated Sutton turns out some fine work. The book concludes with “Na and the Dredspore of Gruaga,” a wordless comics story by Alex Niño told in a series of splash panels. It’s a gorgeous set of cosmic vistas detailing a quest to save a terminally ill child. Thankfully, the reproduction of the fine lines of the art works, here as elsewhere, and Niño’s art is a pleasure to look at even at paperback size. Lovely dramatic compositions are given an odd humanism by organic linework, and the fantastic quest’s given an emotional core by the clear stakes. The storytelling’s a bit of a challenge — Preiss includes a quick summary after the story proper — but the gist certainly comes across, while the art encourages meditation on the tale overall.

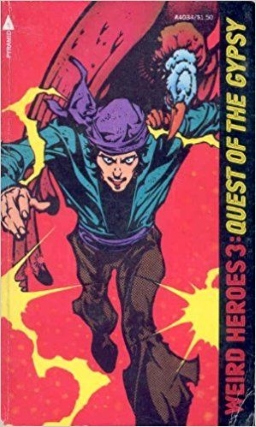

Preiss followed the first two anthology volumes with three novels. The first is Ron Goulart’s Quest of the Gypsy, again illustrated by Alex Niño. It reprints the story from Weird Heroes Volume One, then extends it to follow the lead character through adventures with a futuristic Spanish Inquisition, exploits in Gibraltar, and a struggle against a city of robots. The novel’s virtues and failings are much the same as in the original short story, but it’s fair to say that the tale doesn’t suffer from being expanded. (In fact, Preiss mentions plans to publish a total of six novels featuring the character as he races around the future globe in an attempt to recover his memory; one of a number of plans for Weird Heroes that weren’t to be realised.)

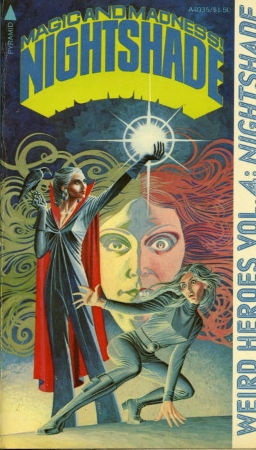

Next is Tappan King and Beth Meacham’s Nightshade, featuring a character King and Meacham created with Mark Arnold. This was the first novel for King and Meacham, who would marry two years after it was published; King would go on to write a number of short stories, co-write another novel (1985’s Down Town), and edit The Twilight Zone magazine. Meacham would write several short stories and a number of non-fiction books about science fiction and fantasy, and would have a long career as an editor for Ace Books and Tor Books, serving as editor-in-chief of the latter. The book boasts art by Rudy Nebres and an introduction by Walter Gibson, whose recollection of reading the Sherlock Holmes stories as they came out helps anchor the book and the series as a whole in a living tradition of heroic fiction. He gives the story his blessing — concluding the introduction “May Nightshade long continue to uphold the tradition of The Shadow” — and there are some parallels between the story here and the first Shadow novel. That story introduced the lead character from the outside and slowly revealed his operatives and powers. Something of the same is done here, and the writing is similarly terse, if occasionally also clunky. There isn’t a character we can follow to help us get our bearings at once (as there was in the first Shadow novel), but then there are some interesting and outlandish ideas for corporate villains. Unfortunately, there are some well-intentioned problems here as well.

Next is Tappan King and Beth Meacham’s Nightshade, featuring a character King and Meacham created with Mark Arnold. This was the first novel for King and Meacham, who would marry two years after it was published; King would go on to write a number of short stories, co-write another novel (1985’s Down Town), and edit The Twilight Zone magazine. Meacham would write several short stories and a number of non-fiction books about science fiction and fantasy, and would have a long career as an editor for Ace Books and Tor Books, serving as editor-in-chief of the latter. The book boasts art by Rudy Nebres and an introduction by Walter Gibson, whose recollection of reading the Sherlock Holmes stories as they came out helps anchor the book and the series as a whole in a living tradition of heroic fiction. He gives the story his blessing — concluding the introduction “May Nightshade long continue to uphold the tradition of The Shadow” — and there are some parallels between the story here and the first Shadow novel. That story introduced the lead character from the outside and slowly revealed his operatives and powers. Something of the same is done here, and the writing is similarly terse, if occasionally also clunky. There isn’t a character we can follow to help us get our bearings at once (as there was in the first Shadow novel), but then there are some interesting and outlandish ideas for corporate villains. Unfortunately, there are some well-intentioned problems here as well.

Firstly, too little is revealed in the end about the main character. Nightshade’s established as a formidably gifted stage magician and mistress of disguise, but her background’s left underdeveloped. So too are hints of multiple personalities reflected in her various identities (I’ll note that this is another idea that would be picked up by another hero of about the same era, as Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz’s Moon Knight would play about with similar notions). More bemusing is the turn the plot takes when the (White) Nightshade disguises herself as a (Black) Haitian to join a Communist uprising in Haiti in the course of her quest for vengeance. You can’t help but notice the unlikeliness of this working out, and how Nightshade uses the Haitians as a way to further her own personal goals. Overall, the character has potential, but it doesn’t come out in this particular story.

The fifth Weird Heroes book is Doc Phoenix, also titled The Oz Encounter. Ted White’s Doc Phoenix is back in a story largely written by veteran Marvel writer/editor Marv Wolfman (and illustrated again by Stephen Fabian), due to White having to deal with medical issues and rebuilding his house after a fire. This case involves Phoenix working to help a politician’s young daughter whose dreams revolve around darker versions of the Oz books. While I’ve liked much of Wolfman’s work in the past, I don’t think this is among his better efforts. The prose is pedestrian, and the imagery of Oz never really comes alive. I will say it’s one of the first attempts I know of to present a grimmer take on Baum’s world. The plot’s competent, but despite some clever twists, the climax taking place in the waking world feels prosaic after the dream-visions of Oz and elsewhere.

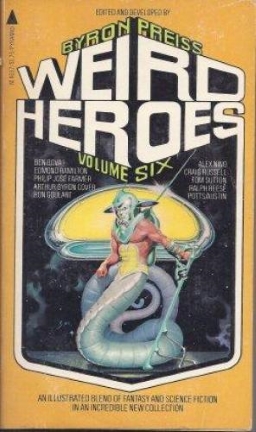

Volume Six of Weird Heroes opens with Preiss telling an anecdote about how the lead story came to be. Preiss recalls visiting Continuity Associates, an artists’ studio run by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano; there, he spotted a drawing by one of the Continuity artists, Carl Potts (which had been inked by Terry Austin). It was an image of a half-man and half-serpent figure in a space suit. From today’s vantage point, it looks like a precursor image of the character of Sarigar from Alien Legion, the comic Potts would go on to co-create for Marvel’s Epic Comics imprint. At any rate, Preiss was taken by the nobility of the character, and decided after long pondering of the illustration that the creature was a detective. He then called Ron Goulart, and assigned him to write a story about the character, who he’d given the name Shinbet. After all that, “Shinbet Investigates” is a bit of a letdown. It’s a competent enough comedy-detective story, but the SF aspects feel halfhearted and not thought through; it struck me as vaguely reminiscent of some lost segment from the Heavy Metal movie (complete with gratuitous nude large-breasted woman). The pacing’s better than the other comedy bits in Weird Heroes, but the mystery’s solved by pulling a science-fictional explanation out of thin air. Notably, the wonder and nobility Preiss found in the original illustration is completely missing.

Volume Six of Weird Heroes opens with Preiss telling an anecdote about how the lead story came to be. Preiss recalls visiting Continuity Associates, an artists’ studio run by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano; there, he spotted a drawing by one of the Continuity artists, Carl Potts (which had been inked by Terry Austin). It was an image of a half-man and half-serpent figure in a space suit. From today’s vantage point, it looks like a precursor image of the character of Sarigar from Alien Legion, the comic Potts would go on to co-create for Marvel’s Epic Comics imprint. At any rate, Preiss was taken by the nobility of the character, and decided after long pondering of the illustration that the creature was a detective. He then called Ron Goulart, and assigned him to write a story about the character, who he’d given the name Shinbet. After all that, “Shinbet Investigates” is a bit of a letdown. It’s a competent enough comedy-detective story, but the SF aspects feel halfhearted and not thought through; it struck me as vaguely reminiscent of some lost segment from the Heavy Metal movie (complete with gratuitous nude large-breasted woman). The pacing’s better than the other comedy bits in Weird Heroes, but the mystery’s solved by pulling a science-fictional explanation out of thin air. Notably, the wonder and nobility Preiss found in the original illustration is completely missing.

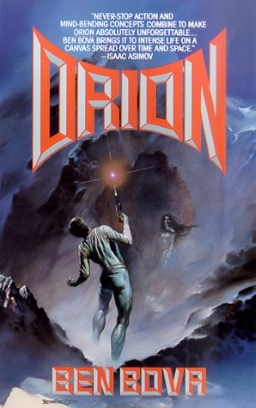

Next came what turned out to be Weird Heroes’ most lasting success: “Orion,” by Ben Bova. It’s a story about a man with superhuman control of mind and body, who uncovers the strange truth that he’s a mythological figure incarnate. He’s thrust into an ongoing conflict between ancient gods, and faces the necessity of great sacrifice to defeat an ancient evil. Bova mixes science fiction and Zoroastrian mythology here, and it’s conceptually an interesting blend. In this specific case, I found the story leans a bit too far toward the science-fictional side of things, spending too much time on the ins and outs of a fusion reactor at a point when the story’s dramatic action should be racing toward a climax. That aside, the tale’s well-plotted, and an interesting beginning to Orion’s story. Also worth noting: the two illustrations to this story come from P. Craig Russell, and they’re gorgeous pieces of work — one a depiction of a shadowy study filled with mysterious items, the other a tense discussion in a super-scientific laboratory. The visual art in this series is generally of a high order, and Russell’s art nouveau line and classical compositions make for some of the best drawings in the whole run of Weird Heroes.

Next comes “Fifty Years of Heroes: The Edmond Hamilton Papers,” a memoir by Hamilton with illustrations by Alex Niño, and afterwords by Julius Schwartz, Forrest Ackerman, and Robert Bloch. It’s a pleasant, rambling look back over Hamilton’s career in comics and science fiction. I don’t know that it’s particularly revelatory, but it provides some interesting sidelights on Hamilton’s work, with offhand notes about, for example, which member of the Legion of Super-Heroes he found it hardest to use in a story (Triplicate Girl). After that is “Greatheart Silver in: The First Command, or, Inglories Galore.” As you might expect, it’s another Greatheart Silver story by Philip José Farmer, illustrated by Tom Sutton. I still don’t connect with Farmer’s sense of humour, and still don’t care much for his prose style. But the plot is sharply constructed, ratcheting up tension on Greatheart nicely and moving through deliberately outrageous coincidences to a bizarre climax. The volume concludes with the Ralph Reese–illustrated “Galactic,” in which Arthur Byron Cover rewrites Beowulf as a science-fictional private eye story. Some interesting ingredients fail to cohere into more than a straight-ahead adventure story; Cover himself in his Afterword characterises the piece as a failure, noting that while it has some slick prose it’s not ultimately revelatory of character. I can’t help but agree.

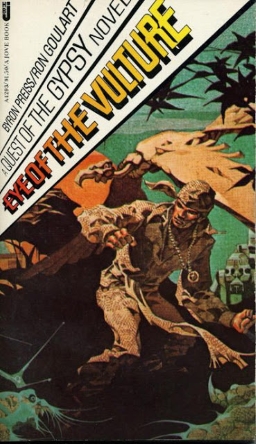

The seventh Weird Heroes book is Eye of the Vulture, the second novel by Ron Goulart, again illustrated by Alex Niño, again featuring his amnesiac lead character struggling through a run-down future in search of answers. Here much of the action takes place in Africa, and if the setting’s mostly effective, one can’t help but notice a couple of scenes in dubious taste. For example, a despotic African ruler is described as “… a parody of a Black man, this bobbing character. He was out of place, a refugee from the stereotype-laden movies of the twentieth century. He was obviously patterned after the urban American pimp more than anything else. …” Preiss’ introduction to the book, describing Goulart as a satirist, rings a bit hollow — it’s not clear what he’s satirising in this way, and Goulart’s other book in the same world didn’t feel especially satiric. The story’s the usual fast-paced plot-oriented adventure tale with an oddly dark ending. The projected six-book series ends here, plot points mostly wrapped up, but with the heroes left in an equivocal if not dark place.

The seventh Weird Heroes book is Eye of the Vulture, the second novel by Ron Goulart, again illustrated by Alex Niño, again featuring his amnesiac lead character struggling through a run-down future in search of answers. Here much of the action takes place in Africa, and if the setting’s mostly effective, one can’t help but notice a couple of scenes in dubious taste. For example, a despotic African ruler is described as “… a parody of a Black man, this bobbing character. He was out of place, a refugee from the stereotype-laden movies of the twentieth century. He was obviously patterned after the urban American pimp more than anything else. …” Preiss’ introduction to the book, describing Goulart as a satirist, rings a bit hollow — it’s not clear what he’s satirising in this way, and Goulart’s other book in the same world didn’t feel especially satiric. The story’s the usual fast-paced plot-oriented adventure tale with an oddly dark ending. The projected six-book series ends here, plot points mostly wrapped up, but with the heroes left in an equivocal if not dark place.

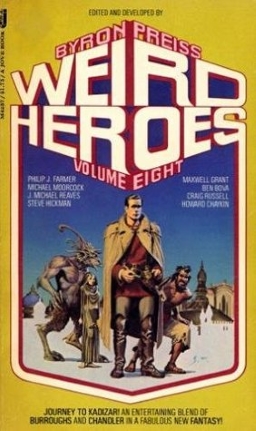

The eighth and final volume is another anthology. It begins with a reprint of Michael Moorcock’s story “The Deep Fix,” originally published in 1963. Moorcock, in his afterword and elsewhere, has spoken of the story as a kind of transitional piece between heroic fiction and more experimental modernist writing — in an interview with the Los Angeles Times he said the story “was about as close to Burroughs as I’ve ever written and … was intended as a kind of bridge for a reader between the fantasy they were reading in the magazine [Science Fantasy] and what I was enjoying in the Olympia Press Burroughs books.” I don’t see the kind of stylistic experimentation that’d imply, but the imagery Moorcock produces is certainly striking. What seems like a chaos of archetypes becomes rationalised by the end of the story, which, as Moorcock’s afterword implies, tends to undermines the power of the whole thing. Nevertheless, there’s something fascinating in the image of the last sane man in the world desperately taking drugs to keep himself from hallucinating, only to find himself slipping into a deeper world that may be his only hope. It all makes for a solid tale, here illustrated by Howard Chaykin.

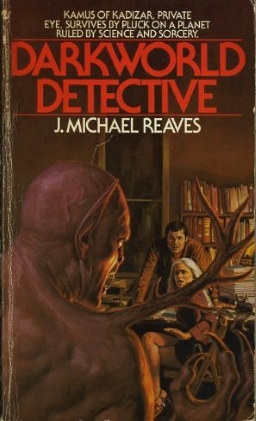

The next story is the first of two in the book by J. Michael Reaves, both starring a PI named Kamus in a fantasy world that also exists within a science-fictional universe. Reaves (who would go on to be part of the Emmy-award-winning writing team for Batman: The Animated Series) would republish these two stories together with two more as a one-volume collection in 1981, Darkworld Detective, and in 1988 John Shirley would write a novel featuring Reaves’ character — Kamus of Kadizar: The Black Hole of Carcosa. The two stories here, illustrated by Stephen Hickman, are extremely well-written imaginative pulp. Action moves smoothly, plot complicates nicely, and character’s illuminated by the time all’s said and done. The stories work as mysteries, use magic well and effectively, and draw from the complexities of mixing the fantasy world and the science-fictional culture beyond. They’re some of the most satisfying work in the whole series.

Between the two Kamus stories is another installment of Ben Bova’s Orion series, “Floodtide.” It takes place in a different era than the first story, and avoids the complexity of scientific detail. The atmosphere’s more cosmic pulp adventure than mythic grandeur, but not bad for all that. The meta-story advances, if slightly, and a good action tale unfolds well. It’s followed by the second Kamus story, and then the concluding story of Weird Heroes, another Farmer pulp parody. This one’s allegedly written by Maxwell Grant, creator of The Shadow, about Kenneth Robeson, creator of Doc Savage. Robeson stumbles through an unlikely action story, meeting a cast of characters who by the end of the story give him the inspiration for his best-known character. As per usual, I don’t care for Farmer’s humour or prose; more to the point, while I can see the appeal of concluding the series with a nod to the original pulps, re-imagining a pulp giant as being inspired by lowbrow misadventures feels more like a fairly dull parody than an homage.

Between the two Kamus stories is another installment of Ben Bova’s Orion series, “Floodtide.” It takes place in a different era than the first story, and avoids the complexity of scientific detail. The atmosphere’s more cosmic pulp adventure than mythic grandeur, but not bad for all that. The meta-story advances, if slightly, and a good action tale unfolds well. It’s followed by the second Kamus story, and then the concluding story of Weird Heroes, another Farmer pulp parody. This one’s allegedly written by Maxwell Grant, creator of The Shadow, about Kenneth Robeson, creator of Doc Savage. Robeson stumbles through an unlikely action story, meeting a cast of characters who by the end of the story give him the inspiration for his best-known character. As per usual, I don’t care for Farmer’s humour or prose; more to the point, while I can see the appeal of concluding the series with a nod to the original pulps, re-imagining a pulp giant as being inspired by lowbrow misadventures feels more like a fairly dull parody than an homage.

At any rate, that’s the series. What does it all add up to?

Like most anthologies, I’d say Weird Heroes is a mixed bag. There are some tight, focussed, sharply-written stories. There are also some ambling, uninteresting pieces. Personally, I found the humour stories almost uniformly the weakest ones in the whole run, and can’t help but wonder if the series might have done better if there’d been fewer of them, done better. I’d also say the novels are on the whole less interesting than the short stories. The Ron Goulart books are quick, solid adventures — but there’s a certain effect that comes from the shorter work, from seeing one story after another, setting after setting, character after character. The best stories justify the “new pulp” tag, being strong tales of memorable heroes.

Let’s look at Preiss’ own hopes for the series. He wanted a modern-day sort of pulp, a pulp with less violence and perhaps a greater social awareness. On the whole I think he achieved that. The use of private eyes in a number of the stories means that you’re looking at characters who solve problems by their wits. Violence is certainly common in the stories, but it’s never the last word. Even in something as lurid as Englehart’s “Viva,” there’s something more going on, some symbolic affirmation of life. Generally the stories balance conflict and action with an avoidance of violence as the central element of the story.

Given that Preiss at one point specifically mentioned the racism and sexism of the pulps as something he wanted to avoid, it’s worth considering how he did there. It’s probably accurate to say that he did avoid the kinds of stereotypes and misogyny that the worst of the pulps featured. On the other hand, some of the stories strike me as, let’s say, having issues. As far as I can tell, while the stories depict a reasonable range of ethnicity, most of the creators are white men; I note two women writers across eight books. This is perhaps all a long way of saying that while the books had the ideals of the mid-1970s, they had the blind spots of the mid-70s as well.

Given that Preiss at one point specifically mentioned the racism and sexism of the pulps as something he wanted to avoid, it’s worth considering how he did there. It’s probably accurate to say that he did avoid the kinds of stereotypes and misogyny that the worst of the pulps featured. On the other hand, some of the stories strike me as, let’s say, having issues. As far as I can tell, while the stories depict a reasonable range of ethnicity, most of the creators are white men; I note two women writers across eight books. This is perhaps all a long way of saying that while the books had the ideals of the mid-1970s, they had the blind spots of the mid-70s as well.

That’s naturally easier to see now, in what is perhaps a more idealistic and certainly overall less violent time. But did Preiss, in the end, create the new kind of pulp he wanted? Did he make something that lasted the way the pulps of the 30s and 40s did? At first blush, you’d have to say no. Eight books isn’t a bad run, but Preiss clearly had hoped to do more. The series does boast some interesting trivia — the story about Ellison’s pseud0nym, the first time Jim Steranko and Neal Adams appeared in the same book — but at a glance it seems an intriguing dead end.

Except when you look more closely that’s not quite as clear. Ben Bova’s Orion character went on to star in a six-novel series. J. Michael Reaves’ Kamus got two books of his own, and Preiss’ own Guts got a novel. Farmer’s Greatheart Silver stories were reprinted in one volume by Tor, and the Oz Encounter novel was reprinted by Oz specialty publishers Hungry Tiger Press. More than that, consider how many references I made to other pop culture characters of the 70s; how many other characters these Weird Heroes seemed to anticipate. This suggests to me that Preiss succeeded in his basic aim: he created characters that spoke to his time. It just so happened that they didn’t revitalise the whole of the pulp field.

Preiss knew what he wanted to do with these books, and he did it. They’re good packages, with often-astonishing art; if nothing else, one wishes more paperback publishers had followed Preiss’ lead in getting the best comics artists to illustrate prose novels. More than that, the short story anthologies in particular have an admirable focus on creating memorable characters. As an editor Preiss was clearly interested in creating heroes, long-running characters who could become the focus of long-running series. In this he was successful; almost all the main characters come off as potential series leads. Conversely, there isn’t much fine prose here. But then pulp was never about fine prose.

As a whole, read quickly as pulp was intended, the eight books of Weird Heroes can occasionally create the hallucinogenic flicker of weirdness the best pulps and hero comics inspire. They’re wildly uneven, with the novels and humour pieces among the weakest parts. But in their era they largely did what they set out to do. They may still ultimately be historical curiosities. But that just means that they do have their place in the history of heroes, if a curious one.

As a whole, read quickly as pulp was intended, the eight books of Weird Heroes can occasionally create the hallucinogenic flicker of weirdness the best pulps and hero comics inspire. They’re wildly uneven, with the novels and humour pieces among the weakest parts. But in their era they largely did what they set out to do. They may still ultimately be historical curiosities. But that just means that they do have their place in the history of heroes, if a curious one.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Interesting overview. I have several installments on my shelf, but haven’t gotten around to reading them! I pick them up when I come across them at flea markets and used bookstores because of my fondness for ’70s illustrated fantasy paperbacks.

Thanks! Yeah, the books are wonderful visual packages, no doubt about it.