Fantasia 2016, Day 21: Aiming Low to Hit a Silver Heaven (Judge Archer, If There’s A Hell Below, and On the Silver Globe)

Wednesday, August 3, was the last day of the Fantasia International Film Festival. Three full weeks of genre films would wrap up here, and I was looking forward to the three last films of the year. The day would begin with the Chinese martial-arts film Judge Archer (Jianshi liu baiyuan). After that came the independent American movie If There’s a Hell Below, promising a paranoid thriller about whistleblowers and government surveillance. Finally came a movie I’d been eagerly anticipating since the start of the festival, the Polish science-fictional classic from 1977 On the Silver Globe (Na srebrnym globie), a space opera about colonization and war on an alien planet. All three were rewarding, and all three were pleasantly (and increasingly) elliptical.

Wednesday, August 3, was the last day of the Fantasia International Film Festival. Three full weeks of genre films would wrap up here, and I was looking forward to the three last films of the year. The day would begin with the Chinese martial-arts film Judge Archer (Jianshi liu baiyuan). After that came the independent American movie If There’s a Hell Below, promising a paranoid thriller about whistleblowers and government surveillance. Finally came a movie I’d been eagerly anticipating since the start of the festival, the Polish science-fictional classic from 1977 On the Silver Globe (Na srebrnym globie), a space opera about colonization and war on an alien planet. All three were rewarding, and all three were pleasantly (and increasingly) elliptical.

Judge Archer was written and directed by Xu Haofeng. Set in 1917 in a China divided among rival armies, it follows a man (Yang Song) who becomes a supremely skillful archer and uses those skills to judge disputes between martial arts schools. When one of those warlords kills the father of a beautiful woman (Yenny Martin), she asks the man — who has taken the cursed name Judge Archer from his master — to bring him to justice. But the warlord has a beautiful wife (Li Chengyuan), who is tempting the judge to abandon his beliefs. Betrayals and duels follow as the story finally, inevitably, works itself out in a semi-mystical duel.

Xu’s background is worth describing here. A long-time student of martial arts, he wrote a bestselling memoir of one of his masters in 2006, The Bygone Kung Fu World (Shiqu de wulin), then followed with another bestselling book in 2006, Dao Shi Xiao Shan (a title translated as alternately Monk Comes Down the Mountain or A Taoist Monk Plunging Into the Madding Crowd). His books have been characterised as less fantastical than most wuxia tales, with a fascination for cultural elements such as painting and calligraphy, as well as an abiding sense of the loss of a traditional kung fu culture. He directed his first movie, The Sword Identity (Wo kou de zong ji), in 2011. Judge Archer was completed in 2012, but not released until this year; in the interim Xu wrote the script for Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (Yi dai zong shi), then wrote and directed another film, The Final Master (Shi fu). His films tend to shun spectacular wire work in favour of more realistic and intense martial arts duels, often evoking a sense of the importance of kung fu traditions and the passing of those traditions in the modern world.

Xu takes the martial arts very seriously, and sees them within an overall cultural context. He has a vision of what they mean and how he wants to put them on film. So it’s not surprising that Judge Archer is an aesthetically ambitious movie. It’s told in a non-linear fashion, with an eye for visual composition and even for stillness. It did not stike me as an outright feast for the eyes, but did seem consistently thoughtful and subtly inventive.

Xu takes the martial arts very seriously, and sees them within an overall cultural context. He has a vision of what they mean and how he wants to put them on film. So it’s not surprising that Judge Archer is an aesthetically ambitious movie. It’s told in a non-linear fashion, with an eye for visual composition and even for stillness. It did not stike me as an outright feast for the eyes, but did seem consistently thoughtful and subtly inventive.

Perhaps that’s most notable in its fight scenes. They’re used well, as crucial points of the action that reveal and advance character, but they’re also highly varied. Some duels are two combatants sitting opposite each other, striking and blocking at top speed with their hands and arms. Others, as you would expect from a movie named Judge Archer, are built around bows and arrows; the final duel in particular impresses. The fights are shot well and clearly, but also with restraint — stunts are kept within the range of the broadly plausible. At the same time, much as Xu might want it otherwise, these are clearly fight scenes in a film: the skills of the masters idealised, the movements rehearsed. There’s nothing wrong with that at all, but it establishes the film as part of a genre of action films, not an attempt at realism. Given that, the choice of how to stage and film the fights is a matter of choosing a tone and style. The action in the movie works, in other words, not because it is more true to life than other wuxia movies, but because Xu has a clear vision of what he wants his fights scenes to be.

Probably as a result, the fights are fraught with meaning. There is a sense of the fights as ritual; the idea of martial arts as a mystic discipline is never far away. Xu presents his combats as symbolic contests without making the effort either overwrought pretension or a dry exercise in justifying punch-ups. He finds a good middle ground of making violence something that matters to the characters in a specific and unusual way, while still keeping it vaguely credible as violence.

This makes Judge Archer a fine wuxia movie, but I’m hesitant to say it’s a fine movie for people who don’t care for wuxia or genre stories. To start with, although the production design is excellent, there isn’t much of a sense of the historical setting of the film. Why set it in this specific era? What does the political and technological state of the world have to do with the story? If there’s something important in the state of the martial arts traditions the film shows, what is it, and what should we understand about those traditions? I don’t know whether Chinese audiences would see things in the film that I couldn’t, or whether they’d read it differently than I did. I can say only that for myself the setting felt disconnected from the larger story.

This makes Judge Archer a fine wuxia movie, but I’m hesitant to say it’s a fine movie for people who don’t care for wuxia or genre stories. To start with, although the production design is excellent, there isn’t much of a sense of the historical setting of the film. Why set it in this specific era? What does the political and technological state of the world have to do with the story? If there’s something important in the state of the martial arts traditions the film shows, what is it, and what should we understand about those traditions? I don’t know whether Chinese audiences would see things in the film that I couldn’t, or whether they’d read it differently than I did. I can say only that for myself the setting felt disconnected from the larger story.

I would say as well that the characters remain at an odd distance. Their motivations are clear, the pattern of their action is comprehensible — but I found they nevertheless did not come alive. I think that the pattern of the plot may be too clear: there is a sense that the characters are acting merely as they must. Even when they struggle to make a choice there seems to be something immaterial in their indecision. In another kind of movie this might pass as a tragic sense of inevitability. Here it felt to me more like a lack of drama. This is not a particularly predictable movie, and yet the characters seem like pieces in a game making moves according to a strategy you don’t quite see. The patterning is more important than establishing the humanity of the characters. There’s a lack of naturalism, which may well be deliberate.

Judge Archer is an entertaining martial arts movie. It aims at something beyond that, and I’m not sure it entirely succeeds. It certainly comes close, though. It’s worth watching for its stylised kung fu fights, and for its clever structure. It may not capture the depth Xu wants, but the attempt alone is interesting. Sometimes it’s not about hitting the bullseye, but about aiming at the right target; and so it is here.

Judge Archer was my last film of the Festival in the Hall Theatre. For the final time this year I crossed the street to the smaller De Seve. I had two features ahead of me, but first came the short film “Bricks,” which was directed by Neville Pierce from a script by Pierce and Jamie Russell. Two Englishmen are working in a vaulted basement, walling off an alcove. We soon learn that one of the men, William (Blake Ritson), is a wealthy stockbroker who has hired the other, a blue-collar workman named Clive (Jason Flemyng), to do the job. William seems to look up to Clive — or does he? A bottle of wine soon makes an appearance; and the truth of the relationship of the two men comes out. This is a free adaptation of a Poe story, but while it’s shot well and the characters are acted well, the modernisation is fitful. I didn’t get much of a sense why Pierce chose to tell this story with these characters. I would have expected a subtext about class, but I couldn’t see one at first viewing; one character claims to be a “traditionalist,” but I didn’t get much sense of that otherwise. The film’s well-crafted, but there’s an edge of madness in the original text that’s lacking here.

Judge Archer was my last film of the Festival in the Hall Theatre. For the final time this year I crossed the street to the smaller De Seve. I had two features ahead of me, but first came the short film “Bricks,” which was directed by Neville Pierce from a script by Pierce and Jamie Russell. Two Englishmen are working in a vaulted basement, walling off an alcove. We soon learn that one of the men, William (Blake Ritson), is a wealthy stockbroker who has hired the other, a blue-collar workman named Clive (Jason Flemyng), to do the job. William seems to look up to Clive — or does he? A bottle of wine soon makes an appearance; and the truth of the relationship of the two men comes out. This is a free adaptation of a Poe story, but while it’s shot well and the characters are acted well, the modernisation is fitful. I didn’t get much of a sense why Pierce chose to tell this story with these characters. I would have expected a subtext about class, but I couldn’t see one at first viewing; one character claims to be a “traditionalist,” but I didn’t get much sense of that otherwise. The film’s well-crafted, but there’s an edge of madness in the original text that’s lacking here.

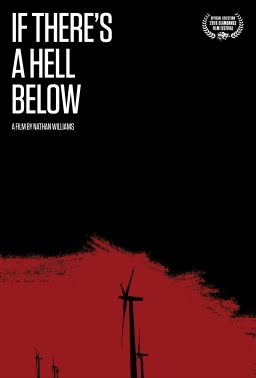

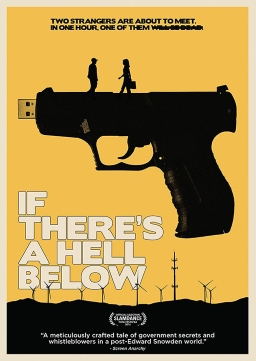

Then came If There’s a Hell Below. Directed by Nathan Williams, and written by Williams from a story he created with his brother Matthew, it’s a fascinating film about espionage, paranoia, and shadowy government agencies. At the same time, it’s also a small, tightly focussed movie that’s built around wide open spaces, careful performances, and an ambiguous narrative structure contrasting different stories certain characters tell certain other characters. Which is to say it has the content of a spy movie with the form of an art-house film, and the union is fascinating.

Somewhere in the wide-open fields of the United States, a journalist named Abe (Conner Marx) arrives for a meeting with Debra (Carol Roscoe), a whistleblower from the bowels of the American deep state. She’s got a flash drive filled with damning information, and she needs to get it out to the media. What information? We don’t know. We don’t really need to. The question isn’t about the information, but about trust: can Debra trust Abe to get the story out? Can he trust her? The opening scene, out of chronological order, shows us something bad happening near a windmill — which grows closer and closer in the background as Abe and Debra drive about. Are they being followed? What is happening here?

This is one of the most visually stunning low-budget films I’ve seen. Much of it takes place while driving, meaning that the scenery is shifting. And yet it’s always beautiful, always interesting to look at. Long handheld takes in a vast landscape subliminally establish an epic background, while the slow place of the edits contrasts with the constant motion of the car through the world. Harvested fields take on a strange tone as Abe and Debra talk through their situation; a physical image of an America vast and desolate, a country compromised by government plots. The talk of surveillance creates a weird sense of claustrophobia, which amps up as another car appears on otherwise empty roads. There’s a sense of the natural landscape, maybe, but a landscape shaped by human effort; yet if the world is shaped by human power, that power is invisible.

This is one of the most visually stunning low-budget films I’ve seen. Much of it takes place while driving, meaning that the scenery is shifting. And yet it’s always beautiful, always interesting to look at. Long handheld takes in a vast landscape subliminally establish an epic background, while the slow place of the edits contrasts with the constant motion of the car through the world. Harvested fields take on a strange tone as Abe and Debra talk through their situation; a physical image of an America vast and desolate, a country compromised by government plots. The talk of surveillance creates a weird sense of claustrophobia, which amps up as another car appears on otherwise empty roads. There’s a sense of the natural landscape, maybe, but a landscape shaped by human effort; yet if the world is shaped by human power, that power is invisible.

There’s a constant feel of paranoia, in other words, which stands out against the wide-open spaces of the film’s setting. This pays off part way through the film, and in a fittingly low-key way. Practicalities of budget aside, what we see works specifically because this isn’t a huge story with helicopters and explosions. This is the kind of story that could be going on all around us, and in a sense certainly is: this is a story about people dealing with trust and betrayal. Debra’s betrayed her bosses. Can she trust Abe? And after the movie shows the consequences of her and Abe’s choices, everything changes — and again we get two characters and a betrayal.

It’s a complex script. It has the skin of a plot-oriented movie, but the guts of a character piece and bones of an art film. There are high stakes — but we never get the details of what they are. The movie isn’t about what exactly is on the key Debra’s got. It’s about what she chooses to do with it. Roscoe does a fine job with a conflicted character; Debra’s not entirely sure she’s doing the right thing. She’s a patriot who believes dark deeds done in shadows are necessary to keep America strong, but she also has a limit. Roscoe gives us a woman fearing for her life while questioning everything she believes in.

And then the structure is more complex and unexpected again, using parallels and contrasts to bring out the theme of the film. Stories play a part. Abe tells Debra a story about his childhood to make a point to her. Something we later learn about that story establishes another layer of meaning to it. And then another story told later in the movie, sharing an element with Abe’s tale, gives us yet another level to think about and sets up a final twist to the ending.

This sounds more complex than it in fact is. But this is clearly a movie with a lot on its mind. If it is about trust and deception, it’s also about storytelling (which, from a certain point of view, traffics in both those things). Debra has a story she needs told. And yet she wants it told in a certain way. She doesn’t want what happened to Edward Snowden’s story to happen again, she tells Abe. She doesn’t want to be a part of the story. She doesn’t want the “human element” to get in the way of the truth. My impression is that the movie wants us to question that; to ask if it’s possible to remove the human element from any story.

This sounds more complex than it in fact is. But this is clearly a movie with a lot on its mind. If it is about trust and deception, it’s also about storytelling (which, from a certain point of view, traffics in both those things). Debra has a story she needs told. And yet she wants it told in a certain way. She doesn’t want what happened to Edward Snowden’s story to happen again, she tells Abe. She doesn’t want to be a part of the story. She doesn’t want the “human element” to get in the way of the truth. My impression is that the movie wants us to question that; to ask if it’s possible to remove the human element from any story.

While the movie mentions Snowden, this is no more a political movie than it is a spy movie. Which is to say that it has the appearance of being about politics, but is actually about something deeper. You can’t help but notice that it deals in some specifically American iconography, both visually and in dialogue. It’s hard not to hear Abe’s name and think “honest.” The story he tells Debra has to do with a cherry tree. So there are specifically American images of truth at play here, reflections on the themes of storytelling, of stories told and not told, of finding truth in tales or finding other kinds of meaning.

This is a movie that requires close attention and audience engagement. Even then, some mysteries aren’t given a clear answer. The title, for example, is taken from a Curtis Mayfield song which is not mentioned in the film; if I hadn’t seen an interview with the director I wouldn’t have known the reference. But to me the movie’s strong enough that it rewards the kind of deep involvement it asks for. It’s unconventional, but still gripping. Things happen at times when you don’t think they will, and when you’re sure the movie’s winding up it turns out to be building up tension again. It’s an espionage story, with tension and violence and unexpected reversals, but there’s nothing standard here. It’s a genre piece, but an elliptical, unusual story that shows how much you can do with genre conventions.

Following the film, director Nathan Williams came out to take questions (what follows, as usual, comes from my handwritten notes). Asked what inspired him to make this movie, Williams said “I just like this sort of movie.” Indie movies always have to be economical, and he had the idea of doing a one-set movie where the set was a car — a set that would move around. That combined with the idea of making a thriller using few characters. He was working on the idea three years ago, when Snowden was in the news. Williams ended up creating a rural thriller, a thriller movie set in wide open spaces, in bright daylight, where you can see everywhere around the characters.

To another question, Williams observed that the movie mostly takes place in real time, and that it’s filled with banal moments to make the scary moments more real: “Because life is ninety-nine percent banal and one percent terrifying.” Williams was then asked whether the opening shot, foreshadowing a harrowing moment much later in the film’s story, had always been planned to begin the movie; he said that it was a decision that came in the editing process, as a strategic choice to catch the attention. He said that the movie was a slow build, and that little happens for the first half hour, so he wanted to create the promise that something dramatic would happen. Once he’d decided that, he was happy to see that the windmills in that opening shot worked as foreshadowing: as the characters drive closer and closer to them, we’re increasingly reminded that something awful’s about to take place.

To another question, Williams observed that the movie mostly takes place in real time, and that it’s filled with banal moments to make the scary moments more real: “Because life is ninety-nine percent banal and one percent terrifying.” Williams was then asked whether the opening shot, foreshadowing a harrowing moment much later in the film’s story, had always been planned to begin the movie; he said that it was a decision that came in the editing process, as a strategic choice to catch the attention. He said that the movie was a slow build, and that little happens for the first half hour, so he wanted to create the promise that something dramatic would happen. Once he’d decided that, he was happy to see that the windmills in that opening shot worked as foreshadowing: as the characters drive closer and closer to them, we’re increasingly reminded that something awful’s about to take place.

Asked about two of the characters in the movie, Williams said that he gave each of the actors long character backgrounds — and then deliberately kept most of that material out of the movie. The idea, he said, was that stories are more interesting with stuff missing, the way the Kennedy assassination is more interesting than the McKinley assassination. Asked about the two stories characters tell in the movie, Williams acknowledged that it was a gamble to take a thriller and spend time on two long monologues not directly related to the plot. He confirmed that the stories were connected, with characters not telling the truth. A name turns up in both referring to the same character; one ends in death and the other in resurrection, and these things are not coincidence.

After a practical question about whether a character would have been able to accomplish a task performed on screen (yes, but the editing made you think it was done more quickly than it was), Williams was asked where the film was shot. The answer was that it was filmed in eastern Washington state; while the Pacific Northwest is generally lush and green, east of the mountains it’s dominated by dry wheat fields and abandoned farms. It’s very desolate, he said, with few cars — so when you do see a car on the road near you, it’s terrifying. In answer to the final questions, Williams said he arrived at the structure of the film by overwriting and then taking stuff out; and said his next film would not be a sequel to If There’s A Hell Below (he jokingly encouraged the crowd to write fanfic instead).

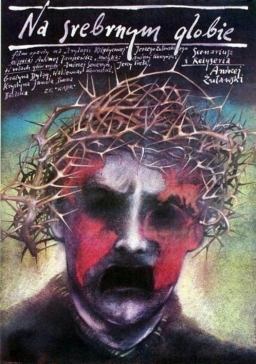

The next film, the last film of the festival, was a restored version of Andrej Żuławski’s 1976 science-fiction epic On the Silver Globe. Jerzy Żuławski was a Polish writer a bit more than a hundred years ago (born in 1874, died in 1915); among his plays, poems, and novels were three science-fiction novels collectively called Trylogia Księżycowa, or The Lunar Trilogy — Na Srebrnym Globie. Rękopis z Księżyca (On the Silver Globe. A Manuscript From the Moon), 1903; Zwycięzca (The Conqueror), 1910; and Stara ziemia (The Old Earth), 1911. I gather the trilogy has been very influential in Europe, but it’s never been translated into English. In 1976, Jerzy Żuławski’s grandnephew Andrej tried to adapt the books into a sprawling epic film. Andrej Żuławski, then a young director, had already had a dramatic career: his second film, 1972’s Diabeł (The Devil), had been banned by the Polish government, leading to Żuławski relocating to France where in 1975 he made L’important c’est du aimer (That Most Important Thing: Love), which did so well he was able to return to Poland and begin making On the Silver Globe. But with the extravagant film about four-fifths complete, the Polish government turned against him again and the production was shut down. Żuławski returned to France, but in 1988 he cobbled together a version of the film using the completed footage and filling in the unshot parts with some narration. In 2016, that version has been newly restored.

The next film, the last film of the festival, was a restored version of Andrej Żuławski’s 1976 science-fiction epic On the Silver Globe. Jerzy Żuławski was a Polish writer a bit more than a hundred years ago (born in 1874, died in 1915); among his plays, poems, and novels were three science-fiction novels collectively called Trylogia Księżycowa, or The Lunar Trilogy — Na Srebrnym Globie. Rękopis z Księżyca (On the Silver Globe. A Manuscript From the Moon), 1903; Zwycięzca (The Conqueror), 1910; and Stara ziemia (The Old Earth), 1911. I gather the trilogy has been very influential in Europe, but it’s never been translated into English. In 1976, Jerzy Żuławski’s grandnephew Andrej tried to adapt the books into a sprawling epic film. Andrej Żuławski, then a young director, had already had a dramatic career: his second film, 1972’s Diabeł (The Devil), had been banned by the Polish government, leading to Żuławski relocating to France where in 1975 he made L’important c’est du aimer (That Most Important Thing: Love), which did so well he was able to return to Poland and begin making On the Silver Globe. But with the extravagant film about four-fifths complete, the Polish government turned against him again and the production was shut down. Żuławski returned to France, but in 1988 he cobbled together a version of the film using the completed footage and filling in the unshot parts with some narration. In 2016, that version has been newly restored.

With all that said, what’s the film about? It opens with a mysterious video record being brought to a scientist, who watches human explorers (Jerzy Gralek, Jerzy Trela, and Iwona Bielska) landing on an alien world. They age slowly, and raise generations of children and grandchildren and multiply-great-grandchildren. These descendants create a primitive society, in which the astronauts are divine figures, sky-fathers and earth-mother. The last of the old astronauts finally dies, after which another astronaut, Marek (Andrzej Seweryn), arrives on the planet. He’s hailed as a messiah, and leads the humans of the silvery planet in war against the aliens native to the planet, birdlike empaths called the Sharn. This does not end well. Meanwhile, even as Marek ascends inevitably to the final situation of most messiahs, we learn why he went to the alien planet and what the watcher of the video record has to do with him.

What I have written is reasonably accurate and also laughably insufficient. You can see elements of the movie’s themes even in that condensed description: an analysis and satire of religion, society, war, colonialism. But there’s more; there’s almost everything in human life, one way or another. There’s a sense in which this is what Northrop Frye might call an anatomy (or Menippean satire), a work in which attitudes or mental states are presented and satirised, a form “characterized by a great variety of subject-matter and a strong interest in ideas.” But there’s a richer sense of the human than you usually get in satire.

What I have written is reasonably accurate and also laughably insufficient. You can see elements of the movie’s themes even in that condensed description: an analysis and satire of religion, society, war, colonialism. But there’s more; there’s almost everything in human life, one way or another. There’s a sense in which this is what Northrop Frye might call an anatomy (or Menippean satire), a work in which attitudes or mental states are presented and satirised, a form “characterized by a great variety of subject-matter and a strong interest in ideas.” But there’s a richer sense of the human than you usually get in satire.

The movie’s deeply mythic, and indeed I would say apocalyptic. It follows the creation of a people and a society, along with their legends, and then follows them through a holy war and the arrival of a prophet-figure. The Sharn aren’t just Others; they’re entities that can see deep into the psyche, creatures who bring the unconscious to the foreground. We see rituals, sacred drug-taking, orgies, sacrifices: all of which feel primal, archetypal.

This works because of the imagery Żuławski puts on screen. This science fiction is not just mythic and unconventional, but excessive and beautiful. The effects are practical and low-tech, avoiding massive explosions for simpler things like filters, make-up, and clever costume design. The silver world comes to feel both real and alien, a place where human beings become something different than they were.

The film leans heavily on its themes and relentless search for meaning, and the dialogue is accordingly non-literal. Characters emote by screaming philosophical questions. Acting styles are deliberately extreme. It’s all too rich to assimilate on one showing, demanding multiple viewings to follow the various branches of the symbols. Exposition is minimal, and much of the early part of the film is a kind proto–found-footage structure; it’s weirdly immersive despite the obvious unreality.

The film leans heavily on its themes and relentless search for meaning, and the dialogue is accordingly non-literal. Characters emote by screaming philosophical questions. Acting styles are deliberately extreme. It’s all too rich to assimilate on one showing, demanding multiple viewings to follow the various branches of the symbols. Exposition is minimal, and much of the early part of the film is a kind proto–found-footage structure; it’s weirdly immersive despite the obvious unreality.

The fact that the movie’s unfinished weirdly helps sustain if not amplify its surreal effect. When we reach a point in the film that was never made, we get scenes of a contemporary city with a voice-over giving a synopsis of the scenes we’re not seeing. This somehow makes the story more powerful. We’re constructing the film in our own heads, basing it off of what we’ve already seen, and contrasting it with something we recognise as “reality.” The effect is to question that reality, to undermine it, to suggest that the history and mythology of the Silver Globe is the real explanation for the world we think we know. These scenes have their own arc, of a sort, visually if in no other way, and end with a perfect metafictional moment. In a movie so concerned with the human search for meaning, and what it suggests is the inherent failure of that search, the voice-over describing the missing fragments of the work of art becomes a tool bringing out the ideas of the film.

This is a movie much closer to Dune (whether Jodorowsky’s unmade film version or David Lynch’s erratic creation) and 2001 than it is to Star Wars. There’s a kind of mysticism underlying a large-scale conflict, but this movie is far more subversive of both those things than Lucas’s. One of the central themes here is the idea of eternal recurrence: things repeat themselves, and so we get images familiar from Earth history and Earth mythology, but made strange. The flaws that made our history what it is can’t be avoided.

This is a movie much closer to Dune (whether Jodorowsky’s unmade film version or David Lynch’s erratic creation) and 2001 than it is to Star Wars. There’s a kind of mysticism underlying a large-scale conflict, but this movie is far more subversive of both those things than Lucas’s. One of the central themes here is the idea of eternal recurrence: things repeat themselves, and so we get images familiar from Earth history and Earth mythology, but made strange. The flaws that made our history what it is can’t be avoided.

This is big-ambition filmmaking. On the Silver Globe is a genre story on the grandest scale. It does things other movies don’t and can’t. It’s not easy viewing, but it is overwhelming. It is the very definition of a flawed masterpiece — that is, a masterpiece that cannot exist without its flaws.

And with that, the Fantasia Festival ended for 2016, and I staggered out of the Concordia Library Building into the night. On the Silver Globe had, like so many Fantasia movies over these past weeks, decentred reality and left me looking on the world around me as something open to question. It had suggested a new kind of vision, a new way to look at the world. That is the power of art and of film; and I can only hope now next year and in the years to come to see more new things in new ways. In the meanwhile, I’ve had time to think over what I saw at Fantasia. One last post will follow this, then; and in that, I will try to articulate what I learned this year about genre and movies.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.