Lost and Found Treasure

|

|

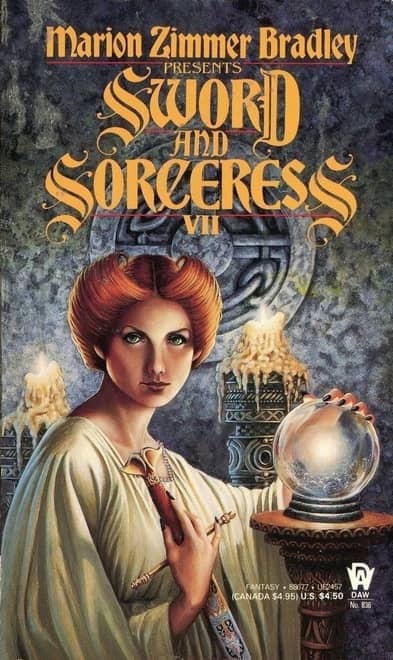

A few weeks ago, I was cruising Facebook when I stopped up short at a familiar image.

It was on our esteemed editor John O’Neill’s wall. And as is often the case with such things, I was struck by a wealth of memories. I received Sword and Sorceress VII as a gift for my 12th birthday. It was probably bought at the B. Dalton in College Mall in Bloomington, IN, one of two easily accessible bookstores on that side of town back in 1990. (Before anyone does the math too fast, yes, I’m celebrating a big birthday next year. It’s in May, if you want to send gift cards for more books.)

I couldn’t tell you exactly which stories were in this volume. I know it had one of Mercedes Lackey’s “Tarma and Kethry” tales in it, but beyond that none of them stand out alone. But as a whole, that volume changed my life as a reader. While I’d feasted on the The Chronicles of Narnia, Robin McKinley, and Susan Cooper, this book was my first exposure to fantasy for grown-ups. And it was full of women.

When I think casually, 1990 doesn’t feel that far away. But in terms of the way women were portrayed in fiction it was another era entirely, and in ways I can’t even begin to explain unless you were there.