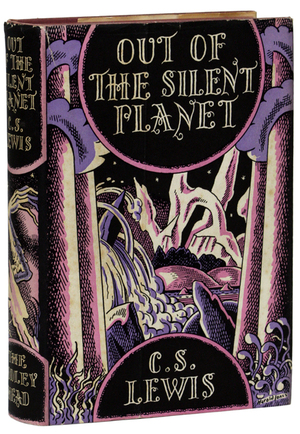

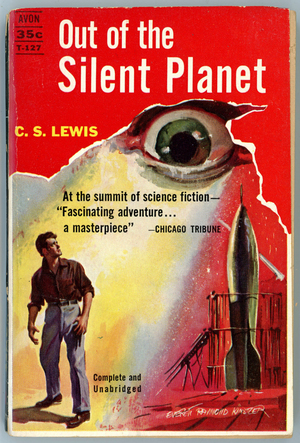

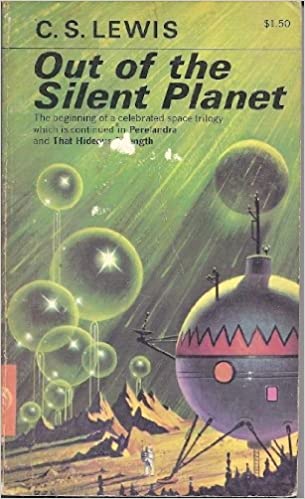

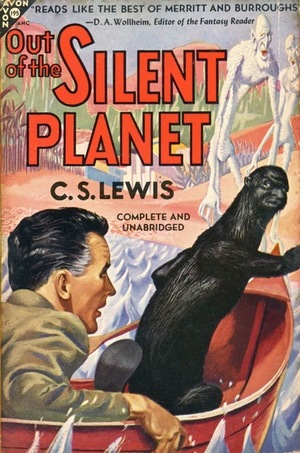

A Cosmic Beginning: Out of the Silent Planet by CS Lewis

CS Lewis’ 1938 novel, Out of the Silent Planet, tells the story of man shanghaied and taken aboard a spaceship to Mars and the deep things he discovers there. In a letter from 1965, JRR Tolkien described how he and Lewis had set themselves the task of writing parallel stories — Tolkien’s a time-journey and Lewis’ a space-journey — where each tale’s protagonist would discover Myth. By that, Tolkien meant that while each story was to be a solid “thriller,” the stories would also contain “a great number of philosophical and mythical implications that enormously enhanced without detracting from the ‘surface adventure’.”

CS Lewis’ 1938 novel, Out of the Silent Planet, tells the story of man shanghaied and taken aboard a spaceship to Mars and the deep things he discovers there. In a letter from 1965, JRR Tolkien described how he and Lewis had set themselves the task of writing parallel stories — Tolkien’s a time-journey and Lewis’ a space-journey — where each tale’s protagonist would discover Myth. By that, Tolkien meant that while each story was to be a solid “thriller,” the stories would also contain “a great number of philosophical and mythical implications that enormously enhanced without detracting from the ‘surface adventure’.”

Elwin Ransom, a philologist (one of several points of similarity with Tolkien), is vacationing by taking a solitary walking tour when he is drugged and kidnapped by Dick Devine and Edward Weston, one, an old and disliked schoolmate, the other, a brilliant scientist.

“You don’t know Weston, perhaps? Devine indicated his massive and loud-voiced companion. “The Weston,” he added. “You know. The great physicist. Has Einstein on toast and drinks a pint of Schrodinger’s blood for breakfast.”

Weston has built a spaceship that has already traveled to another planet and back. On that world, Weston and Devine have discovered great lodes of gold and other precious metals. Now, with Ransom along, they are speeding back through space for more loot. During the month-long trip, Ransom learns that the planet is inhabited and its natives call it Malacandra. At first excited about the voyage despite his forced embarkation, Ransom’s anticipation turns to horror when he learns that he is to serve as sacrifice to monstrous native creatures called sorns.

When Ransom finally sees the sorns, “spindly and flimsy things, twice or three times the height of a man,” he knows he must escape. The sudden arrival of a predatory creature allows the philologist to gain his freedom, but he is soon lost amidst the strange Malacandran landscape and wildlife. It is not until his discovery of another species of Malacandran, bipedal and otter-like, that he begins to understand the planet is maybe not the inimical place Devine and Weston had led him to believe.

The otter creature is named Hyoi and his species is called hrossa. From Hyoi and his neighbors, Ransom begins to learn the language and culture of Malacandra, as well as the fact that it is the planet Mars. While the hrossa are pastoral hunters, another race, the pfifltriggi are builders, and the sorns, thinkers and planners. All are hnau, equal, sentient beings. The hrossa live in the deep canyons that cleave Malacandra’s surface while the sorn populate the high and thin-aired heights above them. The pfifltriggi live in the forested land between.

The otter creature is named Hyoi and his species is called hrossa. From Hyoi and his neighbors, Ransom begins to learn the language and culture of Malacandra, as well as the fact that it is the planet Mars. While the hrossa are pastoral hunters, another race, the pfifltriggi are builders, and the sorns, thinkers and planners. All are hnau, equal, sentient beings. The hrossa live in the deep canyons that cleave Malacandra’s surface while the sorn populate the high and thin-aired heights above them. The pfifltriggi live in the forested land between.

Overseeing the world are ethereal beings called eldil. They in turn are led by the greatest of their number, Oyarsa. All serve Maleldil, the supreme ruler who seems to exist beyond the confines of Malacandra. He also learns that Earth is called Thulcandra — the Silent Planet — though the hrossa don’t know why; that being the sort of thing contemplated by the sorns. It is only later we learn that Earth has been quarantined since its ruling eldil rose up in rebellion against Maleldil. Since then, no word from it has reached any of the other inhabited worlds of the Solar System.

Through his relationship with Hyoi, Ransom becomes captivated by Malacandra and the hrossa. There is an elemental peacefulness to the world and a deep appreciation of life among Hyoi’s people. Even when presented with danger in the form of a hrossa-eating sea monster, the hnakra, there is something life-affirming about his situation.

When he recollected himself they were all on shore, wet, steaming, trembling with exertion and embracing one another. It did not now seem strange to him to be clasped to a breast of wet fur. The breath of the hrossa, which, though sweet, was not human breath, did not offend him. He was one with them. That difficulty which they, accustomed to more than one rational species, had perhaps never felt, was now overcome. They were all hnau. They had stood shoulder to shoulder in the face of an enemy, and the shapes of their heads no longer mattered. And he, even Ransom, had come through it and not been disgraced. He had grown up.

Devine and Weston, though, have not forgotten Ransom, and have continued hunting for him. When Weston and Hyoi disobey Oyarsa’s summons, a series of terrible events is set in motion. Blood is shed, motives are revealed, and the stage is set for a deeper exploration of Out of the Silent Planet‘s cosmogony in the follow-up novels of his Cosmic Trilogy, Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1945).

Devine and Weston, though, have not forgotten Ransom, and have continued hunting for him. When Weston and Hyoi disobey Oyarsa’s summons, a series of terrible events is set in motion. Blood is shed, motives are revealed, and the stage is set for a deeper exploration of Out of the Silent Planet‘s cosmogony in the follow-up novels of his Cosmic Trilogy, Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1945).

Like Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Mars, Lewis’ version is a dying world. Whereas Barsoom is simply old and worn out, Malacandra was ravaged by dark, mysterious forces. Its surface is barren and littered with the bones of long-dead races. Life survives only in the geothermally heated valleys. The descriptions of the planet, its flora, and its fauna, all evolved under weaker gravity than Earth, are beautifully alien.

This time they were much closer. They were enormously high, so that he had to throw back his head to see the top of them. They were something like pylons in shape, but solid; irregular in height and grouped in an apparently haphazard and disorderly fashion. Some ended in points that looked from where he stood as sharp as needles, while others, after narrowing towards the summit, expanded again into knobs or platforms that seemed to his terrestrial eyes ready to fall at any moment. He noticed that the sides were rougher and more seamed with fissures than he had realized at first, and between two of them he saw a motionless line of twisting blue brightness – obviously a distant fall of water. It was this which finally convinced him that the things, in spite of their improbable shape, were mountains; and with that discovery the mere oddity of the prospect was swallowed up in the fantastic sublime. Here, he understood, was the full statement of that ‘perpendicular’ theme which beast and plant and earth all played on Malacandra – here in this riot of rock, leaping and surging skyward like solid jets from some rock fountain, and hanging by their own lightness in the air, so shaped, so elongated, that all terrestrial mountains must ever after seem to him to be mountains lying on their sides. He felt a lift and lightening at the heart.

The efforts at communication and translation between Ransom and Hyoi, and most strikingly between Oyarsa and Weston, are presented in fairly great detail. Tolkien considered them “extremely interesting”, and, whereas “the language difficulty is usually…fudged: here it not only has verisimilitude but also underlying thought.”

The ideas explored in Out of the Silent Planet are rooted in Lewis’ Christianity which gives greater depth to what could have been a simple interplanetary adventure. Raised Christian, Lewis was an atheist from his teens until his thirties. Reasoning with Tolkien and reading George MacDonald and G.K. Chesterton brought him to faith in Jesus, which immediately influenced the direction of his writing.

Already a published poet (pseudonymously), Lewis saw his first novel, The Pilgrim’s Regress published in 1933. Essentially an updated retelling of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, it was explicitly allegorical and Lewis himself later wrote that the book was too obscure and uncharitably tempered. Lewis returned to theological fiction with Out of the Silent Planet, but this time wove the theology more dextrously into the fabric of the story. In fact, it would be easy for someone lacking knowledge of Christianity to miss out on the various theological themes and references in the book. Nonetheless, it is there forming the superstructure of the narrative and infusing the story with a deep-felt Christian humanism, or “hnauism,” to be more precise.

Already a published poet (pseudonymously), Lewis saw his first novel, The Pilgrim’s Regress published in 1933. Essentially an updated retelling of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, it was explicitly allegorical and Lewis himself later wrote that the book was too obscure and uncharitably tempered. Lewis returned to theological fiction with Out of the Silent Planet, but this time wove the theology more dextrously into the fabric of the story. In fact, it would be easy for someone lacking knowledge of Christianity to miss out on the various theological themes and references in the book. Nonetheless, it is there forming the superstructure of the narrative and infusing the story with a deep-felt Christian humanism, or “hnauism,” to be more precise.

In Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men (1930), Lewis saw a dangerous philosophy along the lines of genocidal transhumanism; a desire to spread human-spawned life across the galaxy no matter the cost to other intelligent species. It’s this system of thought that Weston espouses. Countering it, there are strong themes of interspecies comity and anti-colonialism throughout the book. It makes Weston a great villain, one that’s far more interesting and thoughtful than the simply greedy Devine. Unfortunately, it also points the way to where the Out of the Silent Planet fails. Instead of getting to act the part, he just talks and talks and talks.

Everything leading up to the confrontation between Ransom, Weston, and Oyarsa is good, in fact, very good. While the book begins as a straight adventure story, it quickly pivots to the evolution of the solitary Ransom into a man woven into a wider, if alien, society. Lewis makes this compelling through Ransom’s narration and his interactions with the Malacandrans. Instead of that sort of storytelling, the climactic meeting is just a pages long conversation with no tension. Oyarsa is clearly too powerful to feel threatened by Weston and Weston is too condescending and ignorant to realize he is impotent in this situation. There are some delightfully insane declarations by Weston, but it all comes across as little more than a mouse screaming at a lion. It’s a terrible letdown. I’m not sure if Lewis could have handled it any other way but, while valuable at explaining the story’s universe, it is dramatically listless and unsatisfying.

Lewis does manage to partially salvage the book from that disaster in a clever postscript that includes some sublime images. The section reveals that Out of the Silent Planet is a book written by a friend of Ransom. We also learn that Ransom was annoyed at all the details that needed to be left out in order to condense the story for publication.

Lewis does manage to partially salvage the book from that disaster in a clever postscript that includes some sublime images. The section reveals that Out of the Silent Planet is a book written by a friend of Ransom. We also learn that Ransom was annoyed at all the details that needed to be left out in order to condense the story for publication.

I won’t deny that I am disappointed, but then any attempt to tell such a story is bound to disappoint the man who has really been there. I am not now referring to the ruthless way in which you have cut down all the philological part, though, as it now stands, we are giving our readers a mere caricature of the Malacandrian language. I mean something more difficult — something which I couldn’t possibly express. How can one ‘get across’ the Malacandrian smells? Nothing comes back to me more vividly in my dreams … especially the early morning smell in those purple woods, where the very mention of ‘early morning’ and ‘woods’ is misleading because it must set you thinking of earth and moss and cobwebs and the smell of our own planet, but I’m thinking of something totally different. More ‘aromatic’ … yes, but then it is not hot or luxurious or exotic as that word suggests. Something aromatic, spicy, yet very cold, very thin, tingling at the back of the nose – something that did to the sense of smell what high, sharp violin notes do to the ear. And mixed with that I always hear the sound of the singing – great hollow hound-like music from enormous throats, deeper than Chaliapin, a ‘warm, dark noise’. I am homesick for my old Malacandrian valley when I think of it; yet God knows when I heard it there I was homesick enough for the Earth.

I love CS Lewis and have read the Chronicles of Narnia several times, as well as The Screwtape Letters and a stack of his non-fiction. There is much to love in Out of the Silent Planet, and yet I thought I would have loved it more than I do. I know where the Out of the Silent Planet‘s two sequels go and I am intrigued. This was only his second novel and it contains many masterful elements. Nonetheless, this book is like a beautifully painted portrait with a hole through part of its subject’s face.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I think Perelandra is the better novel, but all the Space Trilogy books are topped by Till We Have Faces, which I think is Lewis’ most beautiful and profound book.

Faces is something I’ve been meaning to read for a long time. I think he thought of it the same way

Wonderful excerpts. Nice to learn more about CS Lewis’s writings beyond Narnia.

There’s no book for an adult reader that I have read more often than this one — 16 readings so far. I dearly love every page. Our assessment of the Melidilorn scene differs!

By the way, Ransom’s “A pint of bitter, please” when he (barely) survives the journey back to Earth sent me on a cheerful quest to figure out what that beer might have been like. (I live in rural North Dakota, not England.) After many months of wondering, from what I have been able to gather I did find at last a pretty good approximation, Fargo’s Drumconrath Brewery’s Captain Ferrall English Style Bitter. I’m drinking some as I type.

It’s a session beer. I actually prefer various IPAs, but this is agreeable too. One more good thing I owe to C. S. Lewis.

The content of the conversation is great, and I love that Weston is all in on his convictions, but I found the lack of tension a let down

I remember Brain Aldiss saying in Billion Year Spree that Weston was essentially a caricature of H.G. Wells.

Thanks for this thoughtful review. I love this book a lot. I knew nothing of it when I first read it and it is a delight. I will go digging for Tolkein’s “time story” now, but will ask here too: did Tolkein ever publish his half of this bargain?

He didn’t finish it.

What he did write was decades later edited by his son Christopher and published as The Lost Road.

I didn’t know that, thanks!

I love how Lewis blew up over Stapleton’s “Last and First Men” adding to how fantastic it was. Along with Star-Maker its kind of the “Dr. Caligari” of science fiction. You know, that film if you have a film buff friend (or relative in my case) they try to FORCE you to watch. Then after the “Clockwork Orange” treatment of watching it – “Please… I’ll be good…” and the clamps are removed – well you can’t un-watch it. It’s like almost any sci-fi scenario you can find in Star Maker and social/human in Last and First Men… It’s like it inspired in paragraphs what people made phone book thick trilogies based on. In Lewis’s case it really spawned “Christian Science Fiction”…

Also well I love Lewis’s response. He didn’t freak out and try to “Cancel” Stapledon as both “Concerned Christians” or people of any political spectrum do now. (notably the fake extreme left “Woke” today) He wrote his own books in Counterblaste to it.

I kind of wish I could make Lewis still alive… When the Cash Grab “Dark Tower” came out he could hastily complete that novel of his with the same name, known enough no trademark issue and have a movie made of it to be in theaters at the same time… “It’s your book or this old board game, Mr. Lewis. Your choice. Here are the script cards I made… Care to dictate anything?” Also I’d make him go nuclear over a religion/faith I have for an RPG set in the far future and maybe he’d hack out another book before dying…