Fantasia 2021, Part IV: Tiong Bahru Social Club

The second feature film I planned to see at Fantasia 2021 came bundled with an eight-minute short by a familiar name. That short was “Let’s Fall In Love,” written and directed by Shengwei Zhou, whose odd stop-motion feature S He I reviewed back in 2019. “Let’s Fall In Love” is gentler than S He, visually as well as narratively. A middle-aged man leaves the apartment where he lives alone, and through the eyes of security cameras in the apartment we see his possessions spring to life and interact. They’re playful and affectionate, and there’s something touching about the way they interact with each other and with their human. The animation gives them each a personality, and it culminates in a sweet ending.

The second feature film I planned to see at Fantasia 2021 came bundled with an eight-minute short by a familiar name. That short was “Let’s Fall In Love,” written and directed by Shengwei Zhou, whose odd stop-motion feature S He I reviewed back in 2019. “Let’s Fall In Love” is gentler than S He, visually as well as narratively. A middle-aged man leaves the apartment where he lives alone, and through the eyes of security cameras in the apartment we see his possessions spring to life and interact. They’re playful and affectionate, and there’s something touching about the way they interact with each other and with their human. The animation gives them each a personality, and it culminates in a sweet ending.

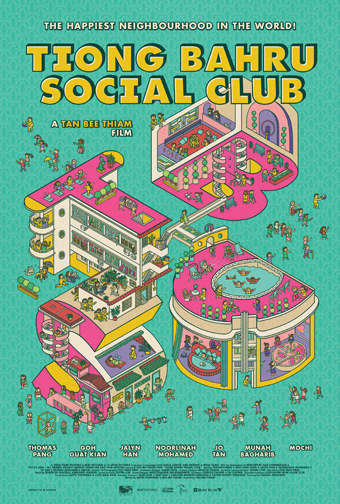

Then the feature: Tiong Bahru Social Club. Directed by Tan Bee Thiam and co-written by Tan with Antti Toivonen, it’s a story from Singapore about Ah Bee (Thomas Pang), a 30-year-old man who loses his job. With the encouragement of his mother (Goh Guat Kian), he gets a new career at the Tiong Bahru Social Club, a housing project that uses algorithms and always-on always-watching AI to ensure perfect happiness for its residents. There are hints of something creepy underneath the surface appearance of the place — but the movie is not that kind of genre story. Mainly we follow Ah Bee as he settles in at Tiong Bahru and makes friends and starts relationships.

As a “happiness agent,” Ah Bee’s responsible for making sure another resident’s happy. But that resident’s a grumpy old cat lady. And Ah Bee himself doesn’t seem too happy — Tiong Bahru residents, of course, have their emotional states monitored 24 hours a day by the AI. The film also cuts away at times to Ah Bee’s mother, in the old apartment she formerly shared with Ah Bee in the massive Pearl Bank Apartments complex. Which some mysterious entity is trying to buy out from under the inhabitants.

As a “happiness agent,” Ah Bee’s responsible for making sure another resident’s happy. But that resident’s a grumpy old cat lady. And Ah Bee himself doesn’t seem too happy — Tiong Bahru residents, of course, have their emotional states monitored 24 hours a day by the AI. The film also cuts away at times to Ah Bee’s mother, in the old apartment she formerly shared with Ah Bee in the massive Pearl Bank Apartments complex. Which some mysterious entity is trying to buy out from under the inhabitants.

So there are a fair number of plot points. But they’re not developed in the ways you might expect, and that’s deliberate. There’s also much material for social satire here, with Tiong Bahru’s “happiness agents” spouting phrases like “everyone’s happiness is our business” and “put unity back in the community!” To say nothing of their trust in the algorithms that underlie the mechanics of the social club. But the movie watches its characters and setting dispassionately, and that approach is (maybe surprisingly) implicitly more empathic than one might expect and certainly more unconventional.

It also requires more active involvement from the viewer; there isn’t much hand-holding here. In particular, Ah Bee both by personality and by the nature of his situation tends to put up a facade of cheeriness over an emotional landscape we soon realise is much bleaker. So we have to pay careful attention to what he does to understand him, and must read his actions and words at one point in the film as informing what he feels at other points. Mostly this works, though his relationship to Tiong Bahru’s AI ends up a little surprising.

It also requires more active involvement from the viewer; there isn’t much hand-holding here. In particular, Ah Bee both by personality and by the nature of his situation tends to put up a facade of cheeriness over an emotional landscape we soon realise is much bleaker. So we have to pay careful attention to what he does to understand him, and must read his actions and words at one point in the film as informing what he feels at other points. Mostly this works, though his relationship to Tiong Bahru’s AI ends up a little surprising.

The obliquity of Ah Bee is deliberate; the emotional blankness of his surface fits nicely into a film deeply concerned with surfaces. The look of the film’s drawn comparisons to Wes Anderson, though Tan has cited Ozu and Tati as his influences; but the point is that the compositions are precise and symmetrical, and the colour work is equally strong — Tiong Bahru is a bright primary-coloured place, nothing worn, nothing decaying. Its surreal artificial hues give the film a dynamic visual identity, but also set up a strong contrast between Tiong Bahru and the lived-in Pearl Bank.

The highly-patterned and artificial look also speaks to the story’s themes, and the order it’s interrogating. Late in the film Ah Bee quotes Lao Tzu on pottery — “It’s the emptiness inside that makes a vessel useful” — and the film explores that thought. Tiong Bahru’s exterior, its concern with performative happiness and objective measurements of emotional states, hides an emptiness where meaning should be. Ah Bee himself hides emptiness behind the appearance of happiness; we see him join Tiong Bahru, and learn how to appear happy to fulfill the requirements of his work and community, and all the while he’s searching for a real and deeper reason for happiness.

The highly-patterned and artificial look also speaks to the story’s themes, and the order it’s interrogating. Late in the film Ah Bee quotes Lao Tzu on pottery — “It’s the emptiness inside that makes a vessel useful” — and the film explores that thought. Tiong Bahru’s exterior, its concern with performative happiness and objective measurements of emotional states, hides an emptiness where meaning should be. Ah Bee himself hides emptiness behind the appearance of happiness; we see him join Tiong Bahru, and learn how to appear happy to fulfill the requirements of his work and community, and all the while he’s searching for a real and deeper reason for happiness.

Wrapped up in these questions are themes of family, love, and community. All of these things have to do with the nature of happiness that the film considers. So too does ambition, and the need for a fulfilling occupation — Ah Bee goes to Tiong Bahru in the first place for work. Perhaps there’s also something of a motif of cycles against straight-line progress implied by the movie’s depiction of technology, and the way that technology’s linked to a certain idea of happiness.

Structurally, the movie’s divided into two sections. The first shows Ah Bee coming to Tiong Bahru and growing more assimilated to its ways, while the second shows him becoming more alienated from it and perhaps finding something better. The structure’s paralleled in a number of ways in the story of the film — a pair of love interests, for example — but the most obvious and most dramatic has to be the contrast between Tiong Bahru and Pearl Bank. Both are real places in Singapore, and in an interesting question-and-answer session Tan spoke about the significance and history the two places have. There is a specifically Singaporean context to the film, then, even a kind of psychogeographical exploration of significant locations in the city and what they mean. The Lao Tzu quote feels relevant here: the buildings in which we live are vessels whose interior emptiness gives them meaning to us.

Structurally, the movie’s divided into two sections. The first shows Ah Bee coming to Tiong Bahru and growing more assimilated to its ways, while the second shows him becoming more alienated from it and perhaps finding something better. The structure’s paralleled in a number of ways in the story of the film — a pair of love interests, for example — but the most obvious and most dramatic has to be the contrast between Tiong Bahru and Pearl Bank. Both are real places in Singapore, and in an interesting question-and-answer session Tan spoke about the significance and history the two places have. There is a specifically Singaporean context to the film, then, even a kind of psychogeographical exploration of significant locations in the city and what they mean. The Lao Tzu quote feels relevant here: the buildings in which we live are vessels whose interior emptiness gives them meaning to us.

So there’s a lot going on in the film. And it is sometimes hard to read, as between the bright surfaces and Ah Bee’s facade there’s a kind of plastic sheen, a difficulty in communicating emotional subtext. Luckily that’s not true when other characters are on screen, who generally are more open and emotionally direct than Ah Bee. But the visual neutrality of Tiong Bahru harmonises in an odd way with the film’s lack of desire to explore what’s actually happening under the place’s surface. This is a movie far more interested in exploring emotional depths than plot points. Or, to put it another way, it’s not interested in exploring character through large-scale plot. The nature of Tiong Bahru is implied in the background, but the point here is not any overarching scheme or the big-picture development of new technologies. This is a small-scale story about human beings caught up in the use of bleeding-edge technology, told often through small choices.

So there’s a lot going on in the film. And it is sometimes hard to read, as between the bright surfaces and Ah Bee’s facade there’s a kind of plastic sheen, a difficulty in communicating emotional subtext. Luckily that’s not true when other characters are on screen, who generally are more open and emotionally direct than Ah Bee. But the visual neutrality of Tiong Bahru harmonises in an odd way with the film’s lack of desire to explore what’s actually happening under the place’s surface. This is a movie far more interested in exploring emotional depths than plot points. Or, to put it another way, it’s not interested in exploring character through large-scale plot. The nature of Tiong Bahru is implied in the background, but the point here is not any overarching scheme or the big-picture development of new technologies. This is a small-scale story about human beings caught up in the use of bleeding-edge technology, told often through small choices.

There’s a lot going on in this movie, and fittingly it’s not always on the surface. Tiong Bahru Social Club is a dry, whimsical satire (in this tonal way the comparisons to Wes Anderson are somewhat justified). But it’s not aiming at merely saying something about the current state of AI or about, say, contemporary fears about privacy and society. Those things are in there, but they’re there as pointers directing us to more substantial and perhaps timeless issues of human happiness and the relation of the individual to the community. At the same time, more importantly, the movie’s also a well-observed empathic comedy. It is a film that is spectacular to look at, surprisingly quiet in its effect, thoughtful, and successful.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.