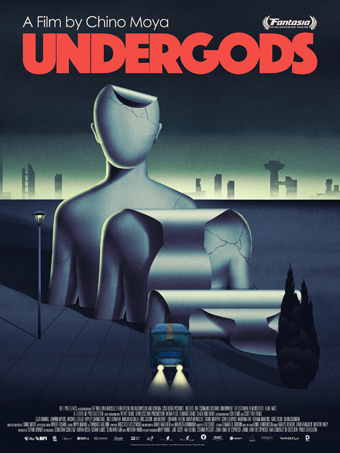

Fantasia 2020, Part XXX: Undergods

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

This year’s Fantasia Festival had a film in that tradition called Undergods. Written and directed by Spaniard Chino Moya, it’s officially a co-production from Estonia, Sweden, Belgium, and the UK. A series of interlaced stories told by a couple of bored men on a long journey by truck, it openly refers to the work of E.T.A. Hoffmann, one of the early masters of the kind of fiction I described above. That made Undergods the second Hoffmann-influenced film I saw at Fantasia after Tezuka’s Barbara, which was inspired by the tales of Hoffmann at several removes. Hoffmann was a writer who played about with doubles and alter-egos — one of his unfinished novels, Kater Murr, imagined the autobiography of a complacent bourgeouis housecat written on the back of letters by a frenzied Romantic composer — so it’s interesting to note that Barbara evoked the content of Hoffmann’s stories without their complexity of form, while Undergods had the form of stories commenting on stories without much of the fantastic content.

The film opens with the truckers (Johann Myers and Géza Röhrig), gathering corpses in a ruined city. They start talking about their dreams, which leads to them telling three stories. In the first, an older man (Michael Gould) and his wife (Hayley Carmichael) take in another man (Ned Dennehy) who claims to be a tenant in their building who’s locked himself out of hs room; he’s helpful, but doesn’t leave, and soon appears to be manipulating them for some unknown reason. From there we pass to a father telling his young daughter about the aftermath of those events, and then launching into a bedtime story. That story’s about an old and wealthy businessman (Eric Godon) who betrays a brilliant but naive architect (Jan Bijvoet); in revenge the architect kidnaps the businessman’s daughter (Tanya Reynolds), leading the businessman to team up with her boyfriend to try to find her — eventually ending up in the city of the corpse-gatherers. The last story begins where the last ended, with a prison in the ruined city, where an inmate (Sam Louwyck) is released to return to his family in a modern city in the developed world; Sam’s wife (Kate Dickie), thinking him dead, has long since married Dominic (Adrian Rawlins) whose perspective we follow as the family tries to adapt to Sam’s reappearance.

There’s an old line that says science fiction literalises metaphors. It’s a line that applies to fantasy and horror, too. It means that, for example, a realist book may say that somebody walking through their old house is haunted by memories like the ghosts of their past, while a horror story might have that person be actually haunted by an actual ghost representing that past. What is metaphor in one case is literal in the other. But still a metaphor, as well, still symbolising something more than itself. Part of the trick of writing stories of the fantastic is knowing how to handle the metaphorical and the literal — knowing exactly how literal to make the literalised metaphor, and how to explore what literalising the metaphor brings the story, and how to explore the metaphor as metaphor while keeping it a literal thing.

There’s an old line that says science fiction literalises metaphors. It’s a line that applies to fantasy and horror, too. It means that, for example, a realist book may say that somebody walking through their old house is haunted by memories like the ghosts of their past, while a horror story might have that person be actually haunted by an actual ghost representing that past. What is metaphor in one case is literal in the other. But still a metaphor, as well, still symbolising something more than itself. Part of the trick of writing stories of the fantastic is knowing how to handle the metaphorical and the literal — knowing exactly how literal to make the literalised metaphor, and how to explore what literalising the metaphor brings the story, and how to explore the metaphor as metaphor while keeping it a literal thing.

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.