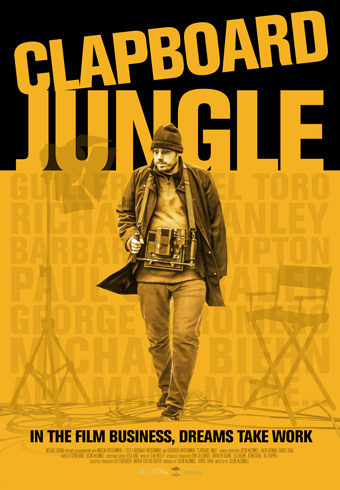

Fantasia 2020, Part II: Clapboard Jungle

Most of the movies I want to see at Fantasia 2020 play at a scheduled time, but quite a few are available on demand for the next two weeks. One of those struck me as a good place to start this year’s unusual Fantasia-from-home: Justin McConnell’s documentary Clapboard Jungle. It’s about the process of putting a film together, focussing not so much on the technical details of directing but the much longer struggle to find financing.

Most of the movies I want to see at Fantasia 2020 play at a scheduled time, but quite a few are available on demand for the next two weeks. One of those struck me as a good place to start this year’s unusual Fantasia-from-home: Justin McConnell’s documentary Clapboard Jungle. It’s about the process of putting a film together, focussing not so much on the technical details of directing but the much longer struggle to find financing.

McConnell’s previous film Lifechanger is the central case study for Clapboard Jungle. That movie played at Fantasia in 2018 (I thought it was a success, despite a few quibbles about plotting and concept), so I knew going in there’d be at least a glimpse of the familiar Hall and De Sève Theatres. I got that, and the sight of a few familiar festival faces. More important, I also got an intriguing documentary that showed the modern film industry from an unusual angle.

The movie’s structured around a video diary McConnell started in 2014, when he set out to make a new film. The movie he ended up making was not the movie he then expected to make, and Clapboard Jungle does a good job following the twists and turns that led him to Lifechanger. The loose narrative works because it gives McConnell a strong frame into which he fits interview snippets with filmmakers, producers, film festival organisers, and other industry people.

These snippets are well-chosen, illustrating the points McConnell wants to make. And they’re edited tightly, giving the film a fast pace, presenting a lot of information and ideas very quickly. McConnell starts with autobiographical material to set up why and how he got into film, but from there keeps a good balance between his personal story and the interviews that make up the larger part of Clapboard Jungle. He’s able to use the structure of the diary and the interviews to maintain a sense of forward narrative momentum while showing the process of arranging financing for a movie, which the film makes clear is a long, tedious, repetitive slog. As well, beyond documenting the stalls and reversals and occasional leap forward of the development process, he also shows himself slowly learning the ropes — going to film festivals and markets, for example. We have the feeling of learning about the process at the same time he does, which gives the documentary a needed sense of progress.

The heart of the film is this long struggle to set up a project, showing by example how a film comes to be — or, more usually, does not come to be. It’s a reminder that every film I or you watch, at Fantasia or elsewhere, beat the odds just by coming into existence. McConnell shows us what those odds really are. It’s a bracing look at a side of the industry that rarely comes into focus for outsiders.

But the main audience for Clapboard Jungle may be aspiring directors. It gives us a director’s perspective: we learn the importance of keeping multiple projects on the go, the necessity of being able to take on the role of a producer or writer as needed, the value of shooting a short film as a proof-of-concept, and how important it is to take advice from others — if it’s the right advice. McConnell might actually have been a bit too conscious of speaking to other directors, as the last quarter or so of the film, following him as he actually makes Lifechanger, feels like a departure from the documentary’s focus: instead of talking about the marketplace behind filmmaking, it talks about the process of working with other professionals on and around a set. It seems like useful information, but a different kind of information than we’ve had up to that point.

But the main audience for Clapboard Jungle may be aspiring directors. It gives us a director’s perspective: we learn the importance of keeping multiple projects on the go, the necessity of being able to take on the role of a producer or writer as needed, the value of shooting a short film as a proof-of-concept, and how important it is to take advice from others — if it’s the right advice. McConnell might actually have been a bit too conscious of speaking to other directors, as the last quarter or so of the film, following him as he actually makes Lifechanger, feels like a departure from the documentary’s focus: instead of talking about the marketplace behind filmmaking, it talks about the process of working with other professionals on and around a set. It seems like useful information, but a different kind of information than we’ve had up to that point.

There’s also a point in the film where McConnell reflects that as difficult as it is for him to get a movie made, as a white man he has it easier than others; this sets up a chunk of interviews dealing with diversity in film, and the lack of same. It’s a necessary subject, but coming where it does the film’s discussion of these issues feels shoehorned in. On the other hand, it’s difficult to see how else he could have set it up. I note that at one point McConnell shows himself excited to have met the Weinsteins, as a voice-over reminds us this was before the scandals around Harvey Weinstein surfaced; I wonder if that might have been a more natural point to begin discussing the challenges for non-males and non-whites.

Notably absent in the film is a lack of discussion of aesthetics. This is not necessarily a problem for Clapboard Jungle‘s discussion of the industry, but in terms of McConnell’s personal story one starts to wonder what kind of film it is that he wants to make. You get a sense of the range of his movie interests from his interview subjects — Paul Schrader and George Romero and Guillermo del Toro (who has the clever observation that industry people now speak of ‘content’ and ‘pipelines,’ words typically used for sewage and oil) but also Lloyd Kaufman and Mick Garris and Frank Henenlotter. That covers a wide range of film, which I assume is the point, but means that McConnell’s own perspective on why he’s doing what he’s doing remains enigmatic.

Notably absent in the film is a lack of discussion of aesthetics. This is not necessarily a problem for Clapboard Jungle‘s discussion of the industry, but in terms of McConnell’s personal story one starts to wonder what kind of film it is that he wants to make. You get a sense of the range of his movie interests from his interview subjects — Paul Schrader and George Romero and Guillermo del Toro (who has the clever observation that industry people now speak of ‘content’ and ‘pipelines,’ words typically used for sewage and oil) but also Lloyd Kaufman and Mick Garris and Frank Henenlotter. That covers a wide range of film, which I assume is the point, but means that McConnell’s own perspective on why he’s doing what he’s doing remains enigmatic.

Still, the perspective on what it is one has to do to get a movie made is valuable. It’s an angle rarely seen in movies about movies, whether fiction or documentary, and it feels important: it follows the money. Clapboard Jungle may be especially useful to filmmakers, but there’s value also for everyday viewers in seeing the mechanics determining what shows up on their local movie screens. You get a sense of how long it takes for a film to come together — not least by seeing how many interviewees have died since the start of the project in 2014 — and get a sense of how, despite the obstacles, more and more movies get made. Whether those are the right movies, of course, is an open question.

As for Clapboard Jungle, true to the film’s entrepreneurial theme, press notes indicate McConnell’s turning the movie into a TV series under a different name. It’ll aim at being a “film school in a box” over 8 30-minute episodes. After watching the movie version, you wish him the best of luck; not just because he deserves it, but because he’s got a project that deserves it.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.