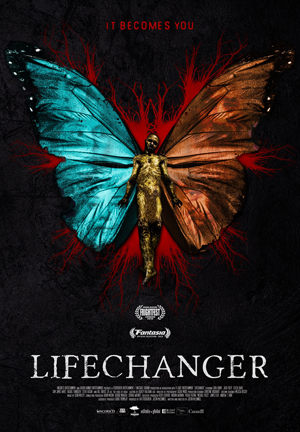

Fantasia 2018, Day 22, Part 3: Lifechanger

For my last movie of 2018 in the Fantasia screening room I selected a Canadian horror movie called Lifechanger. Written and directed by Justin McConnell, it follows an entity named Drew (narrated by Bill Oberst Jr), who, born human, at age 12 developed the ability and need to change bodies with other people (which Drew does repeatedly through the movie, tying the film together with voice-over ruminations; thus the “narrated by” in the previous parenthesis). The process kills the other person, and leaves Drew trapped in a swiftly decaying body. For decades, he’s had to keep changing bodies every few days, the inevitable rot slowed only slightly by doses of cocaine. Lately, though, he’s convinced himself he’s fallen in love with a woman named Julia. Drew wants to be close to her, but how can he do that given what he is?

For my last movie of 2018 in the Fantasia screening room I selected a Canadian horror movie called Lifechanger. Written and directed by Justin McConnell, it follows an entity named Drew (narrated by Bill Oberst Jr), who, born human, at age 12 developed the ability and need to change bodies with other people (which Drew does repeatedly through the movie, tying the film together with voice-over ruminations; thus the “narrated by” in the previous parenthesis). The process kills the other person, and leaves Drew trapped in a swiftly decaying body. For decades, he’s had to keep changing bodies every few days, the inevitable rot slowed only slightly by doses of cocaine. Lately, though, he’s convinced himself he’s fallen in love with a woman named Julia. Drew wants to be close to her, but how can he do that given what he is?

That the question feels meaningful makes the movie a success. It’s odd as a story, with beats in unusual places. Drew never seems too curious about his own nature. Which makes sense; by the time we meet him, he’s resigned himself to the terms of his existence. Still, the movie occasionally feels convenient; his habit of living a few days as one of his victims, for example, feels as though it’d be unsustainable. The plotting here is not the strongest, I think, and I didn’t feel tension build in a traditional way. But it’s an interesting film nevertheless.

This is a small-scale movie, a kind of neighbourhood supernatural horror story set in a suburb of Toronto. It feels a little like the low-budget horror films that filled video store shelves in the 80s, but viewed from a different and somewhat more sophisticated angle. It’s a kind of revisionist horror movie, taking the genre and taking a new look at its framework and structure, keeping what makes those things work while using a different narrative approach. The aim here is not gore, though there is that, but explication of character through the use of horror. As such it succeeds; Drew feels like somebody who’s responding as a human being in an inhuman situation — and so has become inhuman himself, and now accepts the inhumanity as natural.

Drew’s a monster, then, so it’s not surprising that he doesn’t consider being honest with Julia about his nature. The movie manages a tricky balance here: Oberst’s dry narration and the sharp script keep Drew at least interesting, though he’s fundamentally unsympathetic on a number of levels. Drew’s got a certain amount of self-knowledge but views mass-murder as merely a necessity for his own survival; being that self-obsessed, he stalks Julia, in a number of different bodies, trying to find out where she lives and whatever information he can that will help him get close to her.

The fascination of the movie is then the fascination of following a monster. An intelligent monster, one who operates according to baroque rules not of his own making; a creature who is no longer human. There’s a partial explanation for Drew hinted at, once, a mention of a First Nations legend of a people from far to the south and west of the movie’s setting. But explanations aren’t the point. This is not a movie that tries to tie up every loose end.

The fascination of the movie is then the fascination of following a monster. An intelligent monster, one who operates according to baroque rules not of his own making; a creature who is no longer human. There’s a partial explanation for Drew hinted at, once, a mention of a First Nations legend of a people from far to the south and west of the movie’s setting. But explanations aren’t the point. This is not a movie that tries to tie up every loose end.

In fact, I think there’s a good argument that Lifechanger only works so long as you don’t think too closely about its basic set-up, which requires somebody in a fairly small geographical area to die or go missing every few days. The last dozen years or so, Toronto’s seen between about 50 and 75 murders per year in the city proper; if Drew kills one person a week, and he seems to need to change bodies ore often than that, he’s doubling the murder rate of the city all on his own. On the other hand: in 2018 Toronto police arrested a man they believe to be a serial killer responsible for murders potentially stretching back decades, and while I don’t know whether that influenced the making of the film, there was talk of a serial killer’s existence in 2017. I will also note that there’s a couple of scenes involving a farm outside the city that recalls another infamous recent Canadian serial killer. This all may be coincidence, but it does suggest McConnell’s consciously or unconsciously working through some of the country’s recent real-life horrors.

What the movie is about, explicitly, is a search for love or at least connection. It’s a monstrous kind of love, if it can be called love at all, but it is at the heart of Drew’s story in this film: his experience of feeling something for Julia is why we follow him now, in this moment, and it’s why he goes through stresses and changes of a kind he hasn’t gone through in the previous decades. The result is an ending that has some aspects you can see coming, and then some you can’t; it’s satisfying in a way that’s not easily described, perhaps because it has the feel of demonstrating the changes this emotion has worked in Drew. One way or another, he changes, becomes more self-aware, becomes something else. There’s irony there, in that through the rest of the film he’s remained stubbornly himself by becoming other people.

What the movie is about, explicitly, is a search for love or at least connection. It’s a monstrous kind of love, if it can be called love at all, but it is at the heart of Drew’s story in this film: his experience of feeling something for Julia is why we follow him now, in this moment, and it’s why he goes through stresses and changes of a kind he hasn’t gone through in the previous decades. The result is an ending that has some aspects you can see coming, and then some you can’t; it’s satisfying in a way that’s not easily described, perhaps because it has the feel of demonstrating the changes this emotion has worked in Drew. One way or another, he changes, becomes more self-aware, becomes something else. There’s irony there, in that through the rest of the film he’s remained stubbornly himself by becoming other people.

Drew reflects in voice-over about the pull of the pack, but he’s also the most isolated individual on the planet. He amuses himself by taking up the lives of the people he kills, for a short time; but this, I think, is given too much space in the film. I can see why the idea’s symbolically important, and important for Drew’s character, but it feels as though the things it brings to the movie could be brought out more quickly. I will say that the actors playing the different bodies through which Drew moves do a reasonable job of establishing a common flatness, which works with the voice-over to establish who Drew is at any time regardless of what he looks like.

On the one hand, Drew escapes himself and his history and who he is by pretending for short periods of time to be somebody else. On the other hand, his feelings for Julia, what he calls love, pull him toward some more honest accounting of himself, ultimately to face the moral reality of what he’s done to keep on living for decades. Cocaine is a way to escape the self, we’re told at one point; maybe that’s why it keeps Drew’s stolen bodies preserved for a little longer. At any rate, that balance of being the self and escaping the self is an interesting theme in the film. Appropriately for a monster like Drew, the idea of self is important to the story. Drew muses of a neighbourhood bar that it never seems to change, just the people do; it’s a good line, not least because it can be read a couple of different ways. People change.

On the one hand, Drew escapes himself and his history and who he is by pretending for short periods of time to be somebody else. On the other hand, his feelings for Julia, what he calls love, pull him toward some more honest accounting of himself, ultimately to face the moral reality of what he’s done to keep on living for decades. Cocaine is a way to escape the self, we’re told at one point; maybe that’s why it keeps Drew’s stolen bodies preserved for a little longer. At any rate, that balance of being the self and escaping the self is an interesting theme in the film. Appropriately for a monster like Drew, the idea of self is important to the story. Drew muses of a neighbourhood bar that it never seems to change, just the people do; it’s a good line, not least because it can be read a couple of different ways. People change.

And thus the title of Lifechanger. It’s a movie that succeeds because it takes an interesting approach to body horror and monstrosity. It’s narratively confusing, at times, but that’s because its ambitions aren’t entirely to do with standard plotting; it’s asking other questions, dealing with other issues. All told, it works better than I feel it should. It’s a satisfying movie, whose ending is open to interpretation and invites thought. That’s a more than worthwhile accomplishment.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.