Fantasia 2016, Day 9: Horror at Varying Levels of Self-Awareness (Shelley, The Inerasable, and Seoul Station)

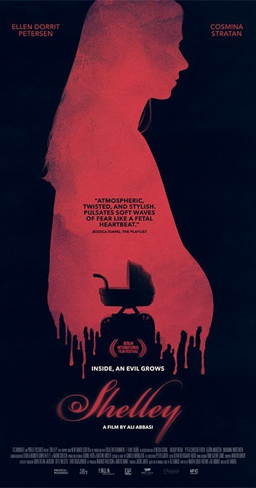

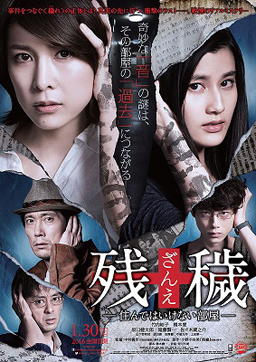

Weekends are busy at the Fantasia International Film Festival, and Friday, July 22, saw things beginning to ramp up for me after a slow few days. After much internal debate, I decided to see three movies, all of them horror films of different kinds. First came the Danish film Shelley, at the Hall theatre, about sinister events around a surrogate mother in an isolated household. Then would come a Japanese film, The Inerasable (Zange —Sunde wa Ikanai Heya), about two women investigating a ghost manifesting in an urban apartment. Finally would come an animated Korean zombie movie, Seoul Station (Seoulyeok). They promised three very different tones. And, as it turned out, delivered nicely.

Weekends are busy at the Fantasia International Film Festival, and Friday, July 22, saw things beginning to ramp up for me after a slow few days. After much internal debate, I decided to see three movies, all of them horror films of different kinds. First came the Danish film Shelley, at the Hall theatre, about sinister events around a surrogate mother in an isolated household. Then would come a Japanese film, The Inerasable (Zange —Sunde wa Ikanai Heya), about two women investigating a ghost manifesting in an urban apartment. Finally would come an animated Korean zombie movie, Seoul Station (Seoulyeok). They promised three very different tones. And, as it turned out, delivered nicely.

Written and directed by Ali Abbasi, Shelley follows a Romanian woman, Elena (Cosmina Stratan), who has agreed to become a live-in maid for a Danish couple, Louise and Kasper (Ellen Dorit Petersen and Peter Christoffersen). They live on their own in an isolated house without electricity, and the movie opens with Elena being driven to their home in the deep woods. As she settles in and becomes friends with her bosses we learn about all three of them — how Elena has a boy back in Bucharest, how she’s struggling to send money back to him, and then on the other hand how Louise and Kasper are vegetarians and raise their own food and want a child of their own which Louise is not physically able to bear. They soon offer Elena enough money to pay for an apartment for her and her boy if she will be a surrogate mother for their child. She agrees, but as the pregnancy goes on problems develop. Health issues; the sort of things a doctor finds normal. But then also more sinister signs. A mysterious crying in the night. Bad dreams. Is the pregnancy cursed?

If so, it’s not clear by what. The feel of horror in this movie is oddly attenuated. There are hints of bad things, but no reason why those bad things are manifesting (if they are). Nor a sense of any specific malevolence. There is a shaman-like seer (Björn Andrésen) who tends to the spiritual need of Elena’s bosses, but although at moments he seems to recognise evil at work, he doesn’t hint at why or what that evil might be.

The vagueness of the narrative is unfortunate, because the movie’s a tremendous technical accomplishment. The natural photography is beautiful, the lighting atmospheric yet real, the sound design spectacular — the sense of place of the house in the woods is remarkable. But the drama that plays out inside the house is undercut by a lack of specificity on the literal story level. There is increasing conflict between Elena and the baby’s parents over the pregnancy, that’s clear, and it works well enough as such. But what touches it off is never given a comprehensible source. I can appreciate the decision to maintain a certain ambiguity about what’s happening, and whether Elena’s increasing fears have a real basis or not. But there’s no hint of a ground out of which those fears could come. No devil, or witch, or ghost. The baby’s sinister or it isn’t. At which point you have to ask: why should it be, then?

The vagueness of the narrative is unfortunate, because the movie’s a tremendous technical accomplishment. The natural photography is beautiful, the lighting atmospheric yet real, the sound design spectacular — the sense of place of the house in the woods is remarkable. But the drama that plays out inside the house is undercut by a lack of specificity on the literal story level. There is increasing conflict between Elena and the baby’s parents over the pregnancy, that’s clear, and it works well enough as such. But what touches it off is never given a comprehensible source. I can appreciate the decision to maintain a certain ambiguity about what’s happening, and whether Elena’s increasing fears have a real basis or not. But there’s no hint of a ground out of which those fears could come. No devil, or witch, or ghost. The baby’s sinister or it isn’t. At which point you have to ask: why should it be, then?

Certain structural choices about the movie and how the story plays out suggest that there has to be something supernatural about the child: a name given in a dream that turns up later on in real life, for example. But the hints never quite cohere. You see them and think that they’re clever linkages that don’t bring out enough of a story to inspire real dread. It is certainly possible at the end of the film to look back over some of the apparent dream sequences and wonder if they were in fact dreams. But if they weren’t — then what? What, in a real sense, does this story matter? Rather than end on a note of terror, it instead seems to simply stop, a final scene or two missing that might have clarified the emotional textures at work.

Certain structural choices about the movie and how the story plays out suggest that there has to be something supernatural about the child: a name given in a dream that turns up later on in real life, for example. But the hints never quite cohere. You see them and think that they’re clever linkages that don’t bring out enough of a story to inspire real dread. It is certainly possible at the end of the film to look back over some of the apparent dream sequences and wonder if they were in fact dreams. But if they weren’t — then what? What, in a real sense, does this story matter? Rather than end on a note of terror, it instead seems to simply stop, a final scene or two missing that might have clarified the emotional textures at work.

By that I don’t mean that the characterisation was lacking. The acting and script serve the characters quite well, in fact; we get to know each of the three leads, understand who they are, see them as people worthy of respect while still being flawed and limited. We sympathise with each of them. Shelley is an unusual horror film in that one hopes for the best for everyone in it. The problem is that we never really fear for anyone. The atmosphere of the brooding woods is evoked wonderfully, but to no tangible effect.

For the first half or so of the movie, this works. There’s a sense of that atmosphere building, and you wait for the explanation, the line, that gives this airy nothing a local habitation and a name. And it never comes, and the threat of the second half is badly undercut. The movie’s hurt by a lack of narrative, not in the foreground plot but in the background informing the events we see. A lack of a legend, of an informing sub-story that would give some heft to the events we watch. The pregnancy at the heart of the movie never feels as sinister as it needs to. There’s no wrongness to the baby, and no real reason there should be a wrongness. You might call Shelley an anti-horror film, which uses horror conventions without the presence of real horror. But what’s it in aid of?

For the first half or so of the movie, this works. There’s a sense of that atmosphere building, and you wait for the explanation, the line, that gives this airy nothing a local habitation and a name. And it never comes, and the threat of the second half is badly undercut. The movie’s hurt by a lack of narrative, not in the foreground plot but in the background informing the events we see. A lack of a legend, of an informing sub-story that would give some heft to the events we watch. The pregnancy at the heart of the movie never feels as sinister as it needs to. There’s no wrongness to the baby, and no real reason there should be a wrongness. You might call Shelley an anti-horror film, which uses horror conventions without the presence of real horror. But what’s it in aid of?

I have some difficulty in seeing what the movie’s about thematically. You can say that it has to do with the exploitation of migrant workers, I suppose. It’s not exactly a reading the film forces, but the subject is there in the basic plot. Except the actual dramatic arc of the film doesn’t draw that theme out in any way I noticed. Why’s the movie titled Shelley? It’s the name of the baby; but why that name, and why make it the title? I couldn’t answer either of those questions.

Shelley’s a frustrating movie. It’s well-done in terms of sight and sound, in terms of character conception, and in terms of the casually-real acting. But it’s obscure about its theme and ideas. And so lacking in narrative, in a reason for the supernatural to be invoked, that some fine atmosphere and chilling moments go for naught. There’s talent here, but a muddled execution.

The Inerasable is a useful contrast. Directed by Yoshihiro Nakamura from a script by Kenichi Suzuki, and based on a novel by Fuyumi Ono, it’s the story of a mystery writer (Yuko Takeuchi) who is contacted by an architecture student, Kubo (the versatile Ai Hashimoto, who also starred in the Parasyte movies this year). Kubo thinks her apartment’s haunted, and the writer — never given a name — works for a magazine that prints serials based on real letters from their readers. The two women investigate the mystery of the ghost, trying to uncover the history of the apartment and of the building. One thing leads to another. The story connects to another story, and another. The two paranormal investigators are soon deeply involved in a kind of horrific psychogeography, uncovering the sinister resonances of the land on which the apartment building was built. But will their quest for the truth draw dark forces down upon them?

The Inerasable isn’t just one story, but a story which contains many stories, and is about stories: stories about architecture, about cities, about the mystery of who lived in spaces before us and what stories they had and what ghosts they’ve left. Does tragedy persist over time? “If that were true, no-one could live anywhere,” says the writer’s husband. She’s not so sure. And what about the new house the two of them are building?

The Inerasable isn’t just one story, but a story which contains many stories, and is about stories: stories about architecture, about cities, about the mystery of who lived in spaces before us and what stories they had and what ghosts they’ve left. Does tragedy persist over time? “If that were true, no-one could live anywhere,” says the writer’s husband. She’s not so sure. And what about the new house the two of them are building?

The plot here is intricate, indeed appropriately labyrinthine. The structure of a magazine writer describing her investigations almost clinically feels slightly old-fashioned, like something out of M.R. James. The nature of the ghosts she finds, bound up with history and place, echo that traditional ghost-story feel. The horror here is delicate most of the way, with flashes of imagery that disturb rather than startle, frighten rather than shock: things that emerge from the ground, things that crawl around among the foundations. Things that are repressed, if you like, things upon which we raise our more conscious structures. The horrors here are the bodies buried beneath our buildings.

The Inerasable is strikingly well-shot, with a still, meditative camera. Geography and place is built not just in three but four dimensions. Again, there’s an almost clinical feel, place and time anatomised for us. As the investigation probes deeper into the past, flashback scenes come to acquire the feel of visual media of past times. The writer’s voice-over moves us swiftly through the details of her investigation, drawing us in to what she sees and finds. Almost without realising it we’re hooked in to the story.

And we watch it build. Slowly the writer and Kubo are drawn back through time, finding one ghost spawned from a tragedy caused by some other ghost, back and further back to a horror at the end of their chain. By this point we have seen the horrors also continue into the present around them. We see them go to lay the original evil to rest, though we know it can’t end well. That’s not the nature of this kind of story.

And we watch it build. Slowly the writer and Kubo are drawn back through time, finding one ghost spawned from a tragedy caused by some other ghost, back and further back to a horror at the end of their chain. By this point we have seen the horrors also continue into the present around them. We see them go to lay the original evil to rest, though we know it can’t end well. That’s not the nature of this kind of story.

Which I think is a key point. Having a horror writer as a lead means that the movie’s unusually self-conscious about form. It’s highly aware of the nature of ghost stories. It is in fact a story about the way stories spread and mutate, as much as it is about the stories we know and the stories we don’t know about the places we live: the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we choose to forget, and the stories hidden for later discovery. “Swapping horror stories often produce a common root,” the writer observes. In these stories images and motifs recur, the past shaping the present, but also story shaping story whether we know it or not. “Ghost stories often have vague or unreasonable elements,” we are also told, early on, but I think it’s an open question whether the vagueness is more apparent than real; whether investigation will reveal at least symbolic explanations, whether emotional truth can feel more valid than rationality. Whether those things are in fact part of the nature of how stories work.

These stories seem often to have an undercurrent of domesticity to them. On one level that makes sense; they’re about things that take place in the home. But there are many suicides for love, many ghosts of dead babies. You wonder how this is meant to reflect on the childless writer and the new home she and her husband have made, or the student about to embark on a professional career. Are these stories signs of change in social roles over time? Or signs of how things remain the same?

These stories seem often to have an undercurrent of domesticity to them. On one level that makes sense; they’re about things that take place in the home. But there are many suicides for love, many ghosts of dead babies. You wonder how this is meant to reflect on the childless writer and the new home she and her husband have made, or the student about to embark on a professional career. Are these stories signs of change in social roles over time? Or signs of how things remain the same?

One can say it’s the nature of stories that they can be read in different ways. So it is that the end of the movie has the writer reading events one way even as we see things undercutting her evaluation. It’s a perfect effect, bringing out the sense of wrongness that so often accompanies horror. “The story is a lure,” she has already told us; sometimes just hearing a tale can bring on a curse. But what’s the alternative? Will history fade away if we don’t know it, or will we be even more helpless in its grip?

The Inerasable is a powerful, profound movie about storytelling and history and ghosts. If you are a writer, is there anything that’s inerasable? If there is, what can be done with it? As a film, The Inerasable is about people struggling with what cannot be wholly erased, what will not submit to being rewritten. It is about the persistence of stories, about what is buried in the detritus of history but sleeps unquietly. It’s about what we build on and how stories we forget contain motifs that shape us. It is an excellently structured film about the stories in architecture and the architecture of stories.

Following that came Seoul Station, an animated film written and directed by Yeon Sang-ho (who also wrote and directed 2014’s animated feature The Fake). It’s one of two films by Yeon at Fantasia about zombies and railways, the other being the live-action Train to Busan; I’ll have a review of that one coming in due course, but for the moment I’ll just say that while I’ve seen some articles bill Seoul Station as a prequel to the live-action movie, the connection isn’t necessary to know about and the two movies stand alone. Seoul Station follows a woman named Hae-sun (Shim Eun-kyung) a former prostitute whose current boyfriend, Ki-woong (Lee Joon), wants her to take up her old trade in order to keep them from being thrown out of their apartment. Fair to say she has problems, but things are about to get worse. Among the homeless who gather around Seoul’s train station an outbreak of a mysterious disease has begun. It spreads rapidly through the area, turning the afflicted into zombies. Will Hae-sun, separated from Ki-woong, find safety?

Following that came Seoul Station, an animated film written and directed by Yeon Sang-ho (who also wrote and directed 2014’s animated feature The Fake). It’s one of two films by Yeon at Fantasia about zombies and railways, the other being the live-action Train to Busan; I’ll have a review of that one coming in due course, but for the moment I’ll just say that while I’ve seen some articles bill Seoul Station as a prequel to the live-action movie, the connection isn’t necessary to know about and the two movies stand alone. Seoul Station follows a woman named Hae-sun (Shim Eun-kyung) a former prostitute whose current boyfriend, Ki-woong (Lee Joon), wants her to take up her old trade in order to keep them from being thrown out of their apartment. Fair to say she has problems, but things are about to get worse. Among the homeless who gather around Seoul’s train station an outbreak of a mysterious disease has begun. It spreads rapidly through the area, turning the afflicted into zombies. Will Hae-sun, separated from Ki-woong, find safety?

The movie has a striking colour sense, uneasy verging into horrific without being too unreal. In fact, the general design sense is extremely realistic, with dense compositions of detailed urban space. There’s a grunge to much of the movie that doesn’t come from clutter or even overt trash, only the capturing of a city moving out of the industrial age. The animation’s effective, if occasionally jerky. Body language is particularly well observed and well realised, though at times the characters seem to sit oddly against the background.

But the movie’s more than just visually striking. It’s got some biting and direct commentary on the homeless and society’s contempt for the homeless. More broadly, as the movie opens the characters are all living on the margins, struggling to survive; and then as the movie goes on we see how brutal and absolute the government response to the zombie epidemic is. The film’s following in the zombie-movie tradition of social satire, and in fact the zombie infestation lets Seoul Station invert the way we normally feel about institutional places. A jail cell is a sanctuary from zombies who can’t get through steel bars. A hospital is the last place you want to go: it’s filled with the infected, brought there by ambulance under the belief that they’re merely sick.

More specifically than that, the film’s concerned with how one makes, or fails to make, a home. The zombie plague starts among the despised homeless. Hae-sun’s faced with being thrown out of her apartment. It’s not too surprising that the bloody climax takes place in a series of salesrooms designed to look like parts of a house — a fake home, a sign of the love of money displacing real emotion.

More specifically than that, the film’s concerned with how one makes, or fails to make, a home. The zombie plague starts among the despised homeless. Hae-sun’s faced with being thrown out of her apartment. It’s not too surprising that the bloody climax takes place in a series of salesrooms designed to look like parts of a house — a fake home, a sign of the love of money displacing real emotion.

Hae-sun’s past as a prostitute, and her repulsion at the prospect of returning to prostitution, is significant here as well. “Is your body so precious?” she’s asked sarcastically at one point. It’s a question that takes on added significance in a zombie movie, a reminder of the power of the image that drives the movie. Here all flesh is merely for consumption. Class bounds are dissolved in universal hunger: everyone’s there to be eaten.

On the other hand, at least the zombies don’t turn on each other. That’s something only the living do, and in this film they do it a lot. Civic authority is challenged, and responds with indiscriminate violence. Good samaritans can be found, but they’re suckers: this is a movie in which no good deed goes unpunished. On the other hand, it’s bleak enough that you can find poetic justice, if you squint: the baddies get theirs, too.

On the other hand, at least the zombies don’t turn on each other. That’s something only the living do, and in this film they do it a lot. Civic authority is challenged, and responds with indiscriminate violence. Good samaritans can be found, but they’re suckers: this is a movie in which no good deed goes unpunished. On the other hand, it’s bleak enough that you can find poetic justice, if you squint: the baddies get theirs, too.

Yeon has a very bitter view of the world, or his movies do. Like The Fake, Seoul Station is very deeply violent. And like that movie, the violence isn’t easy or redemptive. Bad people tend to be the best at being violent, which makes sense; they’re the ones with the most practice at it. This all fits perfectly with the inherent bleakness of a story about the zombie apocalypse. Compared to The Fake, violence is more credible here — or, if it’s incredible, it’s incredible in keeping with the tone of the film.

There’s some real emotional tension in Seoul Station, as well. We don’t entirely know what to make of the relationship between Hae-sun and Ki-woong, so as they separately negotiate the zombie plague we’re pulled back and forth. The main characters do spend much of the movie running and screaming, and one should not expect subtle textures. That’s a real loss, though the way the characters constantly find themselves in situations where they have to force themselves to take greater and greater risks is well-planned. And there is a fine and chilling revelation in the last act that’s unlikely but effective, big enough yet credible enough to be affecting as well as surprising. It fits with the rest of the film: tension and action are very well-timed. Always fast-paced, at only 92 minutes long, the movie keeps ratcheting up the tension while both showing how the epidemic’s playing out on a larger stage and at the same time growing more character-focussed.

There’s some real emotional tension in Seoul Station, as well. We don’t entirely know what to make of the relationship between Hae-sun and Ki-woong, so as they separately negotiate the zombie plague we’re pulled back and forth. The main characters do spend much of the movie running and screaming, and one should not expect subtle textures. That’s a real loss, though the way the characters constantly find themselves in situations where they have to force themselves to take greater and greater risks is well-planned. And there is a fine and chilling revelation in the last act that’s unlikely but effective, big enough yet credible enough to be affecting as well as surprising. It fits with the rest of the film: tension and action are very well-timed. Always fast-paced, at only 92 minutes long, the movie keeps ratcheting up the tension while both showing how the epidemic’s playing out on a larger stage and at the same time growing more character-focussed.

The plot’s very neat, with some good bits of action staging. If there’s a notable amount of coincidence at work (in terms of what one character tells another, and when phones work and when they don’t), there’s little enough of it that one can say it resembles life. Or one can say that it has something of the feel of actual tragedy; just exactly the wrong things left unsaid to set up an ending that has a sense of inevitability.

Seoul Station is a terse, clever, and convincingly nasty zombie movie. Yeon Sang-ho takes advantage of the animated format to deliver a sense of scale, and creates a strong work of horror with action elements. It briefly sets up a host of minor characters who feel individuated and vivid — in the moments before they get killed by zombies. The film has something to say about social inequity and the abandonment of those on the lowest rungs of the social hierarchy, but I think has even more to say about human nature. And none of it uplifting.

Seoul Station is a terse, clever, and convincingly nasty zombie movie. Yeon Sang-ho takes advantage of the animated format to deliver a sense of scale, and creates a strong work of horror with action elements. It briefly sets up a host of minor characters who feel individuated and vivid — in the moments before they get killed by zombies. The film has something to say about social inequity and the abandonment of those on the lowest rungs of the social hierarchy, but I think has even more to say about human nature. And none of it uplifting.

Three movies, three different horrors. All technically excellent. One too lacking in story, the next filled with horror after horror, the third a single tale told at just the right length. Overall an argument for the importance of narrative to genre, perhaps. Seoul Station never explains its zombie plague, just follows events. Shelley explains less. Personally I was most affected by the interwoven stories of The Inerasable. There was a depth of legend to it that was impressive. I have always been taken by stories that play with stories, that use parallel stories or contrasting stories or stories inside stories; that intricate anthology feel works well here. Shelley underplays its genre elements, Seoul Station uses genre adeptly to speak about society and human nature, but The Inerasable is so aware of genre that the awareness becomes a consciousness of form that is, to me, quite beautiful.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.