Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 14: The Visit and The Demolisher

No-one’s a perfect critic, and I’ll readily confess to being less perfect than most. At any rate, sometimes a film’s best appreciated with a certain level of knowledge. Maybe you know too much about the film’s subject, and you see nothing new. Or you know too little, and you find yourself lost. In the latter case, at least, you can wonder whether your lack of knowledge is representative of a general audience, if not of whatever audience the artist has in mind. No critic’s going to be able to hit the sweet spot of knowing just enough, not every time out. Nobody’s perfect.

No-one’s a perfect critic, and I’ll readily confess to being less perfect than most. At any rate, sometimes a film’s best appreciated with a certain level of knowledge. Maybe you know too much about the film’s subject, and you see nothing new. Or you know too little, and you find yourself lost. In the latter case, at least, you can wonder whether your lack of knowledge is representative of a general audience, if not of whatever audience the artist has in mind. No critic’s going to be able to hit the sweet spot of knowing just enough, not every time out. Nobody’s perfect.

Monday, July 27, I saw two movies, both in the De Sève Theatre. The first was a documentary called The Visit, examining what would happen if aliens landed on Earth — what the response would be from human governments and scientific organisations. Then I watched a suspense movie called The Demolisher, about a woman stalked by a mentally-disintegrating police officer. And I found myself wrong-footed in the first case by knowing too much and in the second by knowing too little.

Before The Visit a short film screened: “Testimony of the Unspeakable” (in the original French, “Témoignage de l’indicible”). The director, Simon Pernollet, spoke briefly beforehand setting up the film, a story told by one of his friends about his childhood in Mexico and strange things that happened around his family’s home. We hear a voice telling several anecdotes about unexplained happenings; the stories have the feel of real experiences, in the way they seem to build up an atmosphere more than a connected set of incidents. Meanwhile, the camera moves around an empty house at night, catching shadows, creating an atmosphere and sense of place. At six minutes long, the film manages to subsist on the spooky magical-realist feeling it evokes without feeling as though it’s outstaying its welcome.

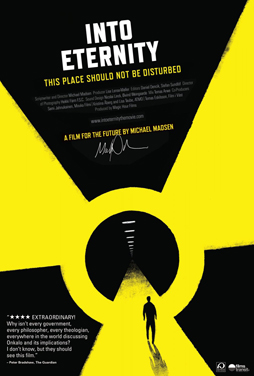

The Visit was written and directed by Danish documentarian Michael Madsen, and is considered to be the second in a documentary trilogy, following 2010’s Into Eternity. Only 90 minutes long, it’s filled with long, still camera shots broken up with various talking heads talking to the camera. These talking heads are officials, former officials, and scientists in governmental or UN agencies, all dealing with the question of how human society and government would react to an alien landing on Earth. Occasionally these experts are encouraged to address the camera, and thus the audience, as if it were the alien — greeting it or us, asking questions, explaining procedures.

The Visit was written and directed by Danish documentarian Michael Madsen, and is considered to be the second in a documentary trilogy, following 2010’s Into Eternity. Only 90 minutes long, it’s filled with long, still camera shots broken up with various talking heads talking to the camera. These talking heads are officials, former officials, and scientists in governmental or UN agencies, all dealing with the question of how human society and government would react to an alien landing on Earth. Occasionally these experts are encouraged to address the camera, and thus the audience, as if it were the alien — greeting it or us, asking questions, explaining procedures.

It’s a good idea, but it isn’t maintained. Much of the movie is simply bureaucrats trying to work out what would happen in the event of an encounter with non-terrestrial life. Unsurprisingly, the scientists have on the whole a better grasp of what the issues are and what to do. Perhaps the most startling thing in the documentary is that apparently nobody at the UN or in the UK government has any plan or protocol established in the event aliens were to land.

We see various retired officials from the UK in particular trying to come to grips with the idea of aliens on Earth. In effect, we’re watching bureaucrats trying to reinvent the history of science fiction, thinking through various possibilities and potentialities and guessing at alien motives. Occasionally this is amusing, as when a former government spokesperson discusses how to present information about the hypothetical alien to the public, emphasising the importance of stressing that the government has things under control and suggesting a celebrity like broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough give the news: “He’s a person everybody trusts, and he knows about wildlife.” But too much of this is too obvious, especially for anyone with any sort of background in reading science fiction — arguably even for people who watch SF media.

I don’t think it’s just a function of my having read a lot of science fiction that leads me to say that the movie would have been better if Madsen had shown more awareness of the SF field. That noted genre publication The Hollywood Reporter challenged the likelihood of Madsen’s scenario, wondering how likely it was that communication between humans and aliens would be possible, and whether aliens would be concerned with the same things humans are. It’s hard to avoid the feeling that Madsen’s skimped on research, and as a result is both reinventing the wheel and missing some truly provocative concepts. That is: had he done more reading of fiction by people who’ve been considering first-contact scenarios for decades, the film might have felt fresher.

I don’t think it’s just a function of my having read a lot of science fiction that leads me to say that the movie would have been better if Madsen had shown more awareness of the SF field. That noted genre publication The Hollywood Reporter challenged the likelihood of Madsen’s scenario, wondering how likely it was that communication between humans and aliens would be possible, and whether aliens would be concerned with the same things humans are. It’s hard to avoid the feeling that Madsen’s skimped on research, and as a result is both reinventing the wheel and missing some truly provocative concepts. That is: had he done more reading of fiction by people who’ve been considering first-contact scenarios for decades, the film might have felt fresher.

There’s a sense where that assessment might be unfair. The most interesting thing in the movie is the way Madsen reverses focus: his alien becomes a mirror, a way for humanity to look at itself. Doug Vakoch of the SETI institute discusses the Voyager spacecraft, and the “golden records” of human accomplishments meant to introduce humanity to anyone in interstellar space who comes across the Voyager probes; he describes debates over what to put on the records, and specifically whether the records should be an honest representation of humanity — whether the records should talk about war. The decision was not to be fully honest on the records. But there’s irony there. One of the speakers on the records was then-UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, who was later notoriously accused of complicity or at least knowledge of war crimes during the Second World War. We can’t get away from our heritage of violence so easily.

Generally the most interesting ideas in the documentary come out of human concepts. A lawyer named Ernst Fasan has an interesting discussion about space law and metalaw, and the obvious lack of a legal framework incorporating alien perspectives. But Wikipedia tells me that metalaw made it into a Heinlein novel in 1958, which returns me to the movie’s problem: all its biggest ideas are familiar. A scientist talking about a ‘second genesis’ of life looking very different from life we know is fine, but if you remember the same basic concepts being explored in a trilogy by Peter Watts several years ago, you’re likely to be less enthralled by the strangeness of the concept here. Essentially, the less you know of science fiction, the more impressive The Visit will be.

Even if you’re new to, say, the idea that humans have effectively been calling out to anyone in the nearby interstellar area through a century’s worth of radio and TV broadcasts, the movie’s got flaws in its own conceptual framework. There’s no mention of NATO in its assumption of an alien landing in England, or any suggestion that some other super-power (naming no names) might try to stick its oar into dealing with the alien. The shift back and forth between narrative strands, and some non-narrative strands, felt unfocussed; the film’s full of images of the streets of Vienna (since the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is located in the United Nations Office in Vienna) and what seemed to be the Hofburg Museum, among various other locations — but the reasons for including specific shots at specific times were difficult to parse.

Even if you’re new to, say, the idea that humans have effectively been calling out to anyone in the nearby interstellar area through a century’s worth of radio and TV broadcasts, the movie’s got flaws in its own conceptual framework. There’s no mention of NATO in its assumption of an alien landing in England, or any suggestion that some other super-power (naming no names) might try to stick its oar into dealing with the alien. The shift back and forth between narrative strands, and some non-narrative strands, felt unfocussed; the film’s full of images of the streets of Vienna (since the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is located in the United Nations Office in Vienna) and what seemed to be the Hofburg Museum, among various other locations — but the reasons for including specific shots at specific times were difficult to parse.

Those images are often striking in and of themselves. Madsen’s compositions have a chilly, formal beauty that occasionally recalls Kubrick. And yet he also has an eye for human incidentals; it’s incredibly pleasing to me to see that the head of the Committee, Policy and Legal Affairs Section of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs has a model of Tintin’s moon rocket on his desk. We get to see these things in long shots, sometimes still but often with the camera moving slowly, smoothly, and inevitably. Almost subsonic soundtrack music meshes with the visuals, brooding but slightly soporific, both adding resonance and yet seeming also to emphasise the emptiness at the film’s heart.

There’s simply too much familiar here, an absence of new and mind-expanding ideas. The stillness of the film emphasises what it lacks. It’s sporadically interesting, but the interest comes when it brings out some aspect of the nature of humanity. How would we as a species deal psychologically with an alien coming to Earth? How would we deal with it leaving? How would we incorporate it into our understanding of the universe, and how would we project our own ideas onto it? All these things are strong questions, raised in the film and dealt with only elliptically. I don’t say that The Visit was obliged to answer them, if they can ever be answered; I can only say that the questions it does involve itself with, and the answers it finds, are much less interesting.

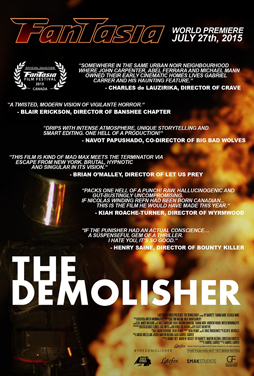

Later that night I returned to the De Sève Theatre to watch the world premiere of a Canadian film called The Demolisher. Written and directed by Gabriel Carrer, it follows a cable repairman named Bruce (Ry Barrett) whose wife, a former policewoman named Samantha (Tianna Nori) has been crippled by a gang of violent criminals. Bruce therefore gets ahold of some body armour and goes after the criminals. But his vengeance is only the beginning; he’s falling apart mentally, and violence becomes his only answer to problems. Meanwhile, the movie’s also been following Marie (Jessica Vano), a young woman trying to recover from an accident to become the runner she used to be. Marie finds a pendant Bruce loses, and this sets up the second half of the film in which Bruce tracks Marie down while, increasingly desperate, she flees the remorseless faceless man in armour.

Later that night I returned to the De Sève Theatre to watch the world premiere of a Canadian film called The Demolisher. Written and directed by Gabriel Carrer, it follows a cable repairman named Bruce (Ry Barrett) whose wife, a former policewoman named Samantha (Tianna Nori) has been crippled by a gang of violent criminals. Bruce therefore gets ahold of some body armour and goes after the criminals. But his vengeance is only the beginning; he’s falling apart mentally, and violence becomes his only answer to problems. Meanwhile, the movie’s also been following Marie (Jessica Vano), a young woman trying to recover from an accident to become the runner she used to be. Marie finds a pendant Bruce loses, and this sets up the second half of the film in which Bruce tracks Marie down while, increasingly desperate, she flees the remorseless faceless man in armour.

A question-and-answer period followed the film, and while I normally discuss my own reactions before recapping a q-and-a period, in this case I think it’ll be more useful to go through what the filmmakers said first. So:

Carrer was onstage along with much of the cast, and said it was the first time he’d shown the movie to people; there’d been no test screenings, and this was only the second time he’d seen it on the big screen himself. Asked how he brought out the film’s atmosphere, he credited the movie’s cinematographer, Martin Buzora (also credited as a producer), calling him a “wizard.” He mentioned having generally small crew. Asked about his inspiration to make the movie, he said that he likes working with actors, and wanted to get away from stories with lots of cuts and practice a piece with minimal dialogue. He would work out blocking with the actors, and do full takes. He mentioned his love of 80s action movies, that he collects VHS, and that he wanted to do an homage to Italian giallo movies.

Asked about the film’s sound design, Carrer acknowledged that it was a huge part of the movie, and discussed working with a sound designer in the UK. He mentioned along the way that there was no script for the film, and that it was ‘written’ on cue cards. That led to a question about how the actors improvised their parts. Ry Barrett talked about how he’d known Carrer for some time, and that Carrer let him do things as an actor; he said he enjoyed using hands and body movements as a part of developing his character. Nori said she had trained in improv, and was given movies to study for her role. She worked extensively with Barrett to develop the details of their characters’ relationship, and a major scene with Barrett’s character breaking down emotionally was entirely improvised based on what they’d worked out. Vano said that she wrote out the monologue from Marie that opened the film.

Asked about the film’s sound design, Carrer acknowledged that it was a huge part of the movie, and discussed working with a sound designer in the UK. He mentioned along the way that there was no script for the film, and that it was ‘written’ on cue cards. That led to a question about how the actors improvised their parts. Ry Barrett talked about how he’d known Carrer for some time, and that Carrer let him do things as an actor; he said he enjoyed using hands and body movements as a part of developing his character. Nori said she had trained in improv, and was given movies to study for her role. She worked extensively with Barrett to develop the details of their characters’ relationship, and a major scene with Barrett’s character breaking down emotionally was entirely improvised based on what they’d worked out. Vano said that she wrote out the monologue from Marie that opened the film.

In response to a question about how much the film’s soundtrack changed the editing, Carrer said it changed a lot, as the soundtrack was worked on for a year, resulting in four hours of music which he gave to the film editor. The next question was about a fairy tale Marie tells to a child she’s babysitting, asking for some explanation of what it meant for the film as a whole. This led to a discussion of what the Demolisher knew and thought he knew, and how the film takes the viewer through a disintegrating mind. Carrer suggested a couple of specific interpretations of the fairy tale, and spoke about the dreamlike nature of the film. Barrett added that he thought the film had a chance to do something different with the idea of the vigilante, and liked the way it left out a lot of backstory and generally left as much open as possible — including the film’s metaphors. Asked if there’d been any discussion over the film’s ending, Barrett said there’d been a lot of debate over who got killed, and different endings were tried at different times. That ended the questions, with Carrer noting that the film would continue on the festival circuit, with a blu-ray release planned for some territories in 2016.

In response to a question about how much the film’s soundtrack changed the editing, Carrer said it changed a lot, as the soundtrack was worked on for a year, resulting in four hours of music which he gave to the film editor. The next question was about a fairy tale Marie tells to a child she’s babysitting, asking for some explanation of what it meant for the film as a whole. This led to a discussion of what the Demolisher knew and thought he knew, and how the film takes the viewer through a disintegrating mind. Carrer suggested a couple of specific interpretations of the fairy tale, and spoke about the dreamlike nature of the film. Barrett added that he thought the film had a chance to do something different with the idea of the vigilante, and liked the way it left out a lot of backstory and generally left as much open as possible — including the film’s metaphors. Asked if there’d been any discussion over the film’s ending, Barrett said there’d been a lot of debate over who got killed, and different endings were tried at different times. That ended the questions, with Carrer noting that the film would continue on the festival circuit, with a blu-ray release planned for some territories in 2016.

Having recounted all that, I want to talk about what choices worked and what didn’t. I would say that a lot of what the filmmakers had in mind made it to the screen: the lack of dialogue, the strong visual sense of the film, the emotional intensity of the actors. But I didn’t feel it succeeded as a whole. I specifically think the lack of a script was a problem. Emotional scenes came with no foreshadowing or follow-up, and the result was the opposite of dreamlike. A dream is the product of a surreal logic that derives from a specific character; the random emotional moments tended to undercut character, leaving the movie feeling disjointed.

Toward the end I did consciously think that the film was trying for a dreamlike sense. Unfortunately, that thought came after a number of implausible plot moments, so the specific thought was along the lines of ‘they may just be trying for a dreamlike sense and failing.’ The film’s unconcerned with plot logic — the Demolisher starts stalking Marie after he randomly spots her in the middle of a large city, she’s randomly saved by a guy with a motorbike who randomly takes her to a garage where she hangs around for a while before the Demolisher randomly finds them again. Action scenes are competently executed, but poorly thought-through. The Demolisher’s stopped at one point by a kick in the nuts, despite the fact that he’s wearing full body armour. The climax involves a pair of cops who turn out to be the two most incompetent policemen in the world, with one of them allowing the Demolisher to grab his gun despite the fact that he’s using it to cover the Demolisher at the time.

Toward the end I did consciously think that the film was trying for a dreamlike sense. Unfortunately, that thought came after a number of implausible plot moments, so the specific thought was along the lines of ‘they may just be trying for a dreamlike sense and failing.’ The film’s unconcerned with plot logic — the Demolisher starts stalking Marie after he randomly spots her in the middle of a large city, she’s randomly saved by a guy with a motorbike who randomly takes her to a garage where she hangs around for a while before the Demolisher randomly finds them again. Action scenes are competently executed, but poorly thought-through. The Demolisher’s stopped at one point by a kick in the nuts, despite the fact that he’s wearing full body armour. The climax involves a pair of cops who turn out to be the two most incompetent policemen in the world, with one of them allowing the Demolisher to grab his gun despite the fact that he’s using it to cover the Demolisher at the time.

If the movie was more stylised, this wouldn’t be a problem. Unfortunately, while it’s well-shot, I found nothing surreal to it. It’s well-shot in the way of a stylish action movie — noir but not Lynch, if you like. I felt that the movie’s long still shots tended, in the case of this specific film, to anchor us to a sense of reality. To place. In other circumstances that editing choice might have helped create an oneiric sense, but something very literal in the visuals that prevented that here. There’s nothing out-of-the-ordinary, merely a camera dwelling on everyday houses and everyday furniture.

I will say that I’ve little experience with the giallo films to which The Demolisher pays homage. But from what I understand there’s more weirdness, and more disturbing violence. The Demolisher does a tolerable job of building atmosphere, but there’s nothing ultimately surprising in it. This was what I meant at the start of this post, when I said sometimes we know too little about a film’s tradition. But does it matter? Can an audience be expected to come to a film with knowledge of its subgenre?

I will say that the movie told an interesting story. Marie is the real protagonist of the film, and how she emerges as the lead is nice to see. Jessica Vano’s performance is particularly strong, and while the plot details of her pursuit by the Demolisher don’t always ring true, her character’s emotional journey helps bring the viewers along. The atmosphere of paranoia and incipient violence is nicely-constructed. The lighting’s effective, particularly in the nighttime chase scenes when the (unnamed) city’s slick with shadow.

But in the end the movie can’t get away from the lack of solid structure I believe is linked to the lack of a thoroughly-worked-out script. There are too many random convenient coincidences, too much that’s not worked through. As noted above, Marie reads a fairy tale that’s obviously meant to parallel and comment on the film’s action. The first problem is that the fairy tale doesn’t have the feel of a fairy tale — it doesn’t have the plot structure of a fairy tale, and the talking animals don’t seem to act like the archetypes you get in fairy tales. The second problem is that it’s unclear how the tale actually comments on the action (note that somebody in the audience actually had to ask about it).

But in the end the movie can’t get away from the lack of solid structure I believe is linked to the lack of a thoroughly-worked-out script. There are too many random convenient coincidences, too much that’s not worked through. As noted above, Marie reads a fairy tale that’s obviously meant to parallel and comment on the film’s action. The first problem is that the fairy tale doesn’t have the feel of a fairy tale — it doesn’t have the plot structure of a fairy tale, and the talking animals don’t seem to act like the archetypes you get in fairy tales. The second problem is that it’s unclear how the tale actually comments on the action (note that somebody in the audience actually had to ask about it).

It does encapsulate the problems with the film. Overall, The Demolisher has some nice elements, is shot well, and has a clearly committed and talented cast. But the script lets it down. Sequences are unmotivated, and the climax goes on too long, wandering around from one ending to another. The people who made it have talent. But the movie’s a good argument that they need a more complete script next time.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.