“Beware the Man With the Stolen Soul”: Steve Ditko and Stalker

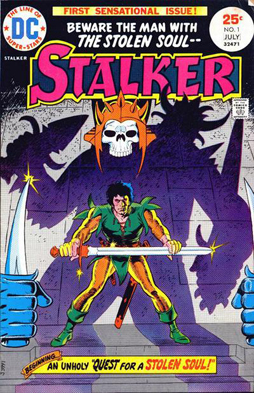

The first stop I made on my shopping expedition last Boxing Day was at my local neighbourhood comics store, which happens to be conveniently located two and a half blocks from my house. There, I found a deal in the back-issue bins: issues 1 to 4 of Stalker, a DC fantasy comic from the 70s. I’d vaguely heard of the title, but knew nothing about it. I thought I remembered hearing that it had good art, which I imagined perhaps meant work by somebody like Nestor Redondo or Ernie Chan. I was way off. In fact, the art was by the remarkable team of Steve Ditko and Wally Wood. As a result, it’s wonderful. And more than that: it’s truly weird fantasy art in every sense.

The first stop I made on my shopping expedition last Boxing Day was at my local neighbourhood comics store, which happens to be conveniently located two and a half blocks from my house. There, I found a deal in the back-issue bins: issues 1 to 4 of Stalker, a DC fantasy comic from the 70s. I’d vaguely heard of the title, but knew nothing about it. I thought I remembered hearing that it had good art, which I imagined perhaps meant work by somebody like Nestor Redondo or Ernie Chan. I was way off. In fact, the art was by the remarkable team of Steve Ditko and Wally Wood. As a result, it’s wonderful. And more than that: it’s truly weird fantasy art in every sense.

Ditko’s one of the most distinctive stylists in American comics. I’ve written before about his supreme accomplishment in fantasy, but Stalker’s an interesting work in its own right. Ditko creates a setting, a very specific world, and does it not by means of creating a consistent dress or coherent architectural style, but by imposing his own specific style and sense of geometric form upon the matter of the story. Wood, in turn, gives a sense of specificity and plausibility to the art, anchoring Ditko’s layouts with a sense of reality: trees, stone walls, suits of armour, all have enough subtle detail that you can feel their weight and mass. Yet at no point does he ever overwhelm Ditko’s pencils with his own style.

The writing, from a young Paul Levitz, is solid. The plot’s tight, fast-moving, and designed around good sword-and-sorcery set pieces. Still, I can’t help but see the book as primarily Ditko’s creation. He’s laid out the action with his usual flair for the expressionistic; he’s designed any number of strange variations on fantasy furnishings (castles, swords, temples, evil priests); and he’s also left certain things alone, drawing from a stock of archetypal medieval imagery so that you can’t help but focus on the weirdness of the main action. The result is not like any other fantasy art I’ve ever seen, but it feels perfectly right for the story.

Ditko actually broke into comics with DC’s horror books in 1953; he moved from there to Charlton Comics, and then also began working for Atlas Comics — later known as Timely and then as Marvel — in the late 50s. When Marvel began a new super-hero line Ditko co-created (or created; stories differ), drew, and seems to have largely written Spider-Man and the Doctor Strange serial in Strange Tales, among a number of other works. He left Marvel in 1966, for reasons that have continued to inspire much speculation. He continued to work at Charlton, briefly returned to DC (where he created super-heroes such as the Creeper and Hawk & Dove), and worked with a variety of smaller publishers for the next few years before returning again to DC in the mid-70s, where he produced Stalker, Shade the Changing Man, and a new iteration of Starman. He’s continued to move back and forth between DC, Marvel, and independent publishers ever since. Perhaps the most notable of his recent works are a number of comics published by his old editor Robin Snyder, which explore Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism — a fascination of Ditko’s since the mid-1960s.

Ditko actually broke into comics with DC’s horror books in 1953; he moved from there to Charlton Comics, and then also began working for Atlas Comics — later known as Timely and then as Marvel — in the late 50s. When Marvel began a new super-hero line Ditko co-created (or created; stories differ), drew, and seems to have largely written Spider-Man and the Doctor Strange serial in Strange Tales, among a number of other works. He left Marvel in 1966, for reasons that have continued to inspire much speculation. He continued to work at Charlton, briefly returned to DC (where he created super-heroes such as the Creeper and Hawk & Dove), and worked with a variety of smaller publishers for the next few years before returning again to DC in the mid-70s, where he produced Stalker, Shade the Changing Man, and a new iteration of Starman. He’s continued to move back and forth between DC, Marvel, and independent publishers ever since. Perhaps the most notable of his recent works are a number of comics published by his old editor Robin Snyder, which explore Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism — a fascination of Ditko’s since the mid-1960s.

Wally Wood began his career in comics in 1948, drawing backgrounds in Will Eisner’s The Spirit, which really is starting at the top. He worked at various jobs over the next few years before arriving at EC Comics. There he produced spectacular work both for Mad and EC’s line of genre comics, becoming known as perhaps the greatest science fiction artist in comics. He went on to work over the next decades for DC, Marvel, and a range of other publishers, including Galaxy Science Fiction, as well as publishing one of the first ‘independent’ comics, witzend. He’d inked Ditko relatively often through the 60s and 70s, which probably helped them on Stalker.

If both Ditko and Wood each had over two decades of experience in comics when Stalker came out in 1975, the same wasn’t true of writer Paul Levitz, who hadn’t been born when either of the other two men started in comics: Levitz was just 19 when the book debuted. He’d moved from being a comics fanzine editor into a position as assistant editor at DC three years earlier. Once there, he’d also written a number of short stories, but Stalker was his first full-length work. He’d go on to a long career as a writer and editor at DC, including a celebrated run on The Legion of Super-Heroes and an extensive career in a number of executive positions.

If both Ditko and Wood each had over two decades of experience in comics when Stalker came out in 1975, the same wasn’t true of writer Paul Levitz, who hadn’t been born when either of the other two men started in comics: Levitz was just 19 when the book debuted. He’d moved from being a comics fanzine editor into a position as assistant editor at DC three years earlier. Once there, he’d also written a number of short stories, but Stalker was his first full-length work. He’d go on to a long career as a writer and editor at DC, including a celebrated run on The Legion of Super-Heroes and an extensive career in a number of executive positions.

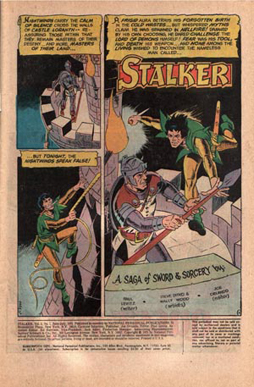

Stalker’s a strong start for a young writer. It catches a real Weird Tales feel, a mix of Howard-like action and Clark Ashton Smith-like strangeness. And it moves like a shot. In the first issue, a strange man in golden chain armour sneaks and fights his way into a castle, where he throws a knife at the ruling queen. It misses, deliberately: the knife carries a message on its blade, a promise that this man, called only ‘Stalker,’ will return in a year to kill the queen. We then go to flashback, where we find Stalker was a beggar who begged the queen to let him serve her as a warrior. She agreed, and brought him into her service — as a slave. He escaped, and, among a crowd of a thousand temples, bitterly decided to take as his patron “the demon lord of warriors — Dgrth!” The diabolical Dgrth appeared before Stalker and gave him “all the arts of killing men ever wished for,” making him undefeatable, but took his soul in exchange.

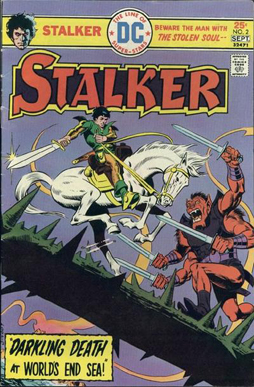

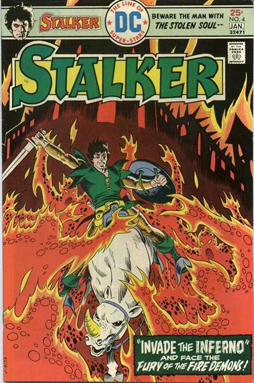

So, back in the present, Stalker finds that revenge on the queen is meaningless; lacking a soul, he cannot feel joy or anything else. He returns to Dgrth’s temple, but the god is absent. Stalker fights the high priest and swears to confront the god himself and regain his soul. Stalker follows this quest for the next two issues. In the fourth issue, he enters the hell where Dgrth dwells and faces the dark god again, producing a new status quo that, had the story continued, would have led to further adventures. As it turned out, that unfortunately didn’t happen.

So, back in the present, Stalker finds that revenge on the queen is meaningless; lacking a soul, he cannot feel joy or anything else. He returns to Dgrth’s temple, but the god is absent. Stalker fights the high priest and swears to confront the god himself and regain his soul. Stalker follows this quest for the next two issues. In the fourth issue, he enters the hell where Dgrth dwells and faces the dark god again, producing a new status quo that, had the story continued, would have led to further adventures. As it turned out, that unfortunately didn’t happen.

In some ways, that might have been for the best. Powerful as these issues are, it’s difficult to see Stalker as an ongoing hero. While his bargain with Dgrth sounds at first blush like a strong set-up for a character, it actually creates two problems. Firstly, Stalker’s supernaturally proficient in combat, meaning fights tend to lose their significance — he can beat any foe, so where’s the danger? Secondly, as we’re told, lacking a soul, he can’t feel emotion strongly. That makes him difficult to empathise with. He’s not just cold, but uninvolved with his own story. In theory, he’s passionate about confronting Dgrth, but how strongly can he really feel about it?

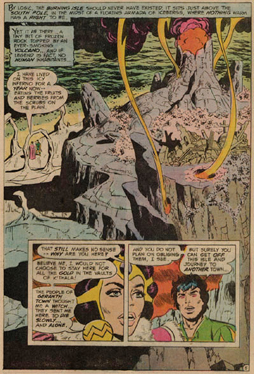

The setting through which Stalker moves is also difficult to feel strongly about as a realistic place; and yet, paradoxically, it has a stronger character than the book’s lead. As a world, it doesn’t have any kind of coherent culture, only a few random references that constitute a rudimentary history, and some place-names which, along with a simple map in one letter column, make for an equally-basic geography. But that’s as much as the story needs. Levitz makes sure the stories take place in dramatic settings: a waterfall at the edge of a world, a frozen island, forbidden temples, lonely bridges of thorns and bones. He throws in pulp strangeness along with it, ancient astronauts and weird gods: this place is an alien planet, we learn, settled by human spacemen centuries past and fallen into medieval barbarity.

What Ditko does with all that is remarkable. You’d expect the artwork in a comic to ground the story, making it more real. Here it does the reverse, pushing the pulp echoes of the narrative into something strange and dreamlike. A cityscape’s dominated not by stone walls or leaden spires, but a temple in the shape of a sword. Stalker himself is a dramatic visual, green jerkin over golden mail with curling black hair and flat red eyes: shining knight, jester, and demon all in one. He’s the perfect hero for the setting, a strange man in a strange land.

What Ditko does with all that is remarkable. You’d expect the artwork in a comic to ground the story, making it more real. Here it does the reverse, pushing the pulp echoes of the narrative into something strange and dreamlike. A cityscape’s dominated not by stone walls or leaden spires, but a temple in the shape of a sword. Stalker himself is a dramatic visual, green jerkin over golden mail with curling black hair and flat red eyes: shining knight, jester, and demon all in one. He’s the perfect hero for the setting, a strange man in a strange land.

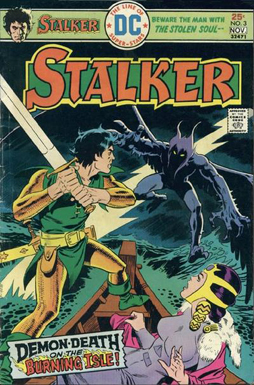

And yet the weirdness builds the setting, because Ditko’s eye is so strong and his mastery of the fundamentals of drawing so great. There’s a page in the third issue dominated by an aerial view of an island; the shapes of the rocks and ruins are like nothing outside of Ditko’s imagination, but the perspective’s so well done and the composition so perfect that there’s an almost three-dimensional sense. It’s literally surreal, more real than real, a perfect balance of form and colour. Some of that has to come from Wood’s inking, lending detail to Ditko’s abstraction. But the curving forms of smoke and rock that shape the page are purely Ditko.

It seems to me that as Ditko’s developed as an artist over the years, his art’s become more abstract and geometrical. You can see that development here, but you can also see how grounded it is in character and emotion. He has a stylised but extremely effective sense of body language; he’s always been an expressionistic artist, distorting angles and heightening shadows, and the twisted, splayed human shapes he imagines are a crucial part of that. It’s something that obviously lent itself particularly to such characters as Spider-Man and the Creeper, both defined by their weirdness and uncanny agility, but it also works here. Stalker’s a man with devil-granted dexterity, not a husky brawler, and Ditko’s art gets across the strangeness and precision of his skill.

It seems to me that as Ditko’s developed as an artist over the years, his art’s become more abstract and geometrical. You can see that development here, but you can also see how grounded it is in character and emotion. He has a stylised but extremely effective sense of body language; he’s always been an expressionistic artist, distorting angles and heightening shadows, and the twisted, splayed human shapes he imagines are a crucial part of that. It’s something that obviously lent itself particularly to such characters as Spider-Man and the Creeper, both defined by their weirdness and uncanny agility, but it also works here. Stalker’s a man with devil-granted dexterity, not a husky brawler, and Ditko’s art gets across the strangeness and precision of his skill.

Along with that is Ditko’s power of storytelling. He’s got an incredible ability to move the reader’s eye across the page as quickly as he wants, to put it exactly where he wants. He moves his camera in and out of a scene with precision; it’s not just a question of transition from panel to panel, but of his ability to make the transitions feel natural. It does what any great comics art does: gives the reader enough information, visually and emotionally, to imagine more of the scene than is actually depicted, while also highlighting the key narrative beats and character reactions. It’s almost startling, creating a rich and weird emotional tone, with the eerie pacing of a classic horror film. Some real credit should be given here to Levitz; a lot of beginning comics writers overburden a page with words, but Levitz is canny enough to be relatively sparing, and allow Ditko to carry a sequence on his own.

At best, there’s a kind of focussed purity to the comic. Each issue has a specific story to tell, and tells it directly and dramatically. The plots are driven by swordplay and sorcery, as Stalker sets himself a goal and moves toward it. Perhaps the best is the third issue, where he comes to a strange island in search of a portal to hell, and one by one overcomes all the monsters standing between him and his goal. There’s something powerful in this figure of a lone hero at the edge of a world, encountering nothing real and nothing normal as he violently makes his way to the villain he’s driven to kill.

At best, there’s a kind of focussed purity to the comic. Each issue has a specific story to tell, and tells it directly and dramatically. The plots are driven by swordplay and sorcery, as Stalker sets himself a goal and moves toward it. Perhaps the best is the third issue, where he comes to a strange island in search of a portal to hell, and one by one overcomes all the monsters standing between him and his goal. There’s something powerful in this figure of a lone hero at the edge of a world, encountering nothing real and nothing normal as he violently makes his way to the villain he’s driven to kill.

Stalker’s never been revived as a series since 1975, though the character himself has returned in one form or another over the years. The complete run’s available as part of a larger collection, The Steve Ditko Omnibus Volume One, along with several short stories by Ditko from various DC anthology books and the nine-issue run of Shade, The Changing Man (one issue of which had never been publicly printed before). I think it’s worth tracking down. It’s fair to say that Stalker’s a lesser work of Ditko’s, but still a reminder of the power in his work. And I think for fantasy fans there’s a further attraction in reading a weird tale with art that’s both as weird and as technically accomplished as the classic prose stories of the field.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Wow. Thanks for that. I’m a big fan of ’70s S&S (Andy Offutt, anyone?), but this was the first I’d heard of this series. I’ll have to see if I can lay my hands on the omnibus.

Matthew,

Wow! I’ve never heard of STALKER – and it sounds like I really missed out.

Thanks for giving me an excuse to finally put down my money for THE STEVE DITKO OMNIBUS. I’m glad DC decided to reprint the series; I’m looking forward to checking it out.

Count me in on being tempted to pick up that omnibus now! Your description of Ditko’s style helped me to appreciate it more, thanks!

I never quite “got” Ditko, but that’s because my exposure to him in my formative years was work he did on Micronauts and it was really jarring after what had come before.

Reading this makes me also think I should track down a copy of the Omnibus.

@Joe H: I was never keen on Ditko in my formative years either. His style was not the splashy Jack-Kirbyesque leaping off the page; his lean, long, stylized lines were so different from the buff comic-book style–which reached its nadir in the ’90s with that whole “Image” look, where the kid next door looks like the Hulk and the Hulk looks like, well, that mountain of growing flesh from Synthetic Men of Mars or something.

I appreciate his work much more now that I’m older, and for all the reasons Matthew described in this review.

Thanks for the good words, everyone!

Ty and John, I was so surprised by the book myself! I always tend to think that comics is a relatively well-scrutinised field, where all the good works have already been identified. But every so often I’m reminded that that’s not really the case — there’s a lot out there that’s relatively neglected. Makes buying back issues a thrill, at least.

Joe and Nick: I absolutely agree that Ditko, especially the post-Silver Age Ditko, can be a bit of an acquired taste. Like Nick said, his stylistic approach is so different than the way most super-hero comics art has developed. But I suspect he’s also a difficult guy to ink. I’ve seen some of his Objectivist stuff, and visually it’s excellent — cartoony and abstract in a way that makes the page live. But for another inker to come in and work on his stuff … I can only imagine the difficulty of working out how to work with that cartooniness and when to play against it. Wood really managed it beautifully.

[…] David Surridge (Black Gate) “Beware the Man With the Stolen Soul”: Steve Ditko and Stalker — “Stalker’s a strong start for a young writer. It catches a real Weird Tales feel, a […]

[…] A. McKillip’s The Changeling Sea. I also often write about comics, and last year I discussed the Steve Ditko/Wally Wood/Paul Levitz run of Stalker from the 1970s; the first volume of Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ Hugo-winning […]