Adventure On Film: Planet Of the Apes

I missed nearly all the seminal pop culture of my youth. When in eighth grade Andy H. asked me which I liked better, AC/DC or Pink Floyd, I honestly couldn’t answer the question. I was also much too tongue-tied to ask Andy if he’d ever heard of Doctor Who, which I’m quite sure he had not.

I missed nearly all the seminal pop culture of my youth. When in eighth grade Andy H. asked me which I liked better, AC/DC or Pink Floyd, I honestly couldn’t answer the question. I was also much too tongue-tied to ask Andy if he’d ever heard of Doctor Who, which I’m quite sure he had not.

Anyway. One of the major events that I missed was Planet Of the Apes. True, Planet is from 1968, and I was only born in ’67, but even so, kids at my school through at least my sixth grade year sported Planet Of the Apes lunch boxes, thermoses, backpacks, and t-shirts. Planet Of the Apes (whatever it was) was cool.

My hipper-than-I friends informed me that Planet regularly played in re-runs on TV, and of course there was the short-lived spin-off series made specifically for the telly (1974). How was it that I had missed all this? Simple: I was building dams in the tributary streams of the Olentangy River, using whatever was handy: stone knives and bearskins, that sort of thing. I knew better than to explain.

Now that I’m older than Methuselah, or at least rapidly catching him up, I figured it’s time to see precisely what I’d missed.

And you know what?

If it weren’t for the execrable presence of Charlton Heston, it’s not half bad.

As a college drinking buddy of mine once opined, with more sarcasm than mere print can deliver, “Charlton Heston couldn’t act his way out of a wet paper bag.” I’d have to agree. Yes, he can champion the NRA, but how on Earth he ever got past a studio cattle call is beyond me.

That said, the film has a couple of killer aces up its sleeve. One is director Franklin J. Schaffner, the helmsman responsible for Patton (1970) and The Boys From Brazil (1978), among others. Another is Rod Serling, who co-wrote the screenplay. A third is Serling’s co-conspirator, Michael Wilson. Don’t be fooled by Wilson’s run-of-the-mill name; he was a heavy hitter whose pen contributed to It’s A Wonderful Life (1946), A Place In the Sun (1951), The Bridge On the River Kwai (1957), and more.

Wilson may have had the stronger resume, but it’s Serling’s Twilight Zone sensibilities that run roughshod over this script, not least at its start, in which three astronauts crash land on some distant planet and immediately debate the merits of their existence, the hopelessness of humanity, and the need to find food. If Heston’s next line had been “There’s a sign-post up ahead,” no savvy viewer would be surprised.

Wilson may have had the stronger resume, but it’s Serling’s Twilight Zone sensibilities that run roughshod over this script, not least at its start, in which three astronauts crash land on some distant planet and immediately debate the merits of their existence, the hopelessness of humanity, and the need to find food. If Heston’s next line had been “There’s a sign-post up ahead,” no savvy viewer would be surprised.

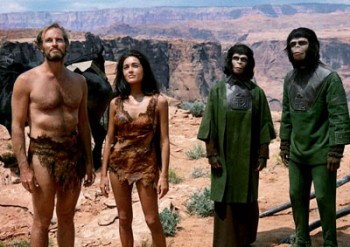

For a time, the scientists meander through a maze-scape of sandstone buttes, alkali flats, and denuded desert, only to stumble into a cornfield where a rabble of primitives are busily helping themselves to crops they clearly didn’t have the savvy to grow. Enter the apes, on horseback no less, and costumed wonderfully in jet-black vests. If their faces are somewhat immobile, the sin is minor; each ape is wonderfully individual.

Heston, as astronaut commander George Taylor, is captured alive and when he wakes in the hospital-cum-cave, he cannot believe what he hears. Surely those wacky ape doctors aren’t speaking…English?

Yes, friends. You’ve just entered the Primate Zone.

The reversal of having a human studied by a “higher” life form (and dismissed as being lower) is hardly new, but Planet Of the Apes succeeds in keeping the scenario lively. Heston’s commander demonstrates (eventually) that he is intelligent, leading the more sympathetic ape-scientists to hotly debate the value of all the truths they hold dear, notably about themselves and the useless evolutionary offshoot they call “man.” When one of the scientists refuses to question any farther and calls the other’s radical views heresy, his opponent says, “How can scientific truth be heresy?” It’s a line worthy of Gene Roddenberry or any of the better Star Trek scriptwriters, all of whom would presumably be horrified to be living today, when science is so routinely pilloried in favor of whatever opinion seems most convenient.

Not that Planet is perfect. Far from it. Leaden exposition abounds. Illogic rears its head. Example: Heston’s Taylor, having been shot in the throat, loses his voice — a terrific plot device, since this leaves him mute when he first becomes a prisoner of the local ape scientists. But once he gets his voice back, there’s no trauma, no raspy quality to his instrument; Heston sounds ready to burst into full-throated baritone song.

Not that Planet is perfect. Far from it. Leaden exposition abounds. Illogic rears its head. Example: Heston’s Taylor, having been shot in the throat, loses his voice — a terrific plot device, since this leaves him mute when he first becomes a prisoner of the local ape scientists. But once he gets his voice back, there’s no trauma, no raspy quality to his instrument; Heston sounds ready to burst into full-throated baritone song.

And how does clever George Taylor convince the apes he’s got an I.Q.? By tossing a paper airplane. The apes are baffled. “Why fly?” they demand. “And where would it get you?” This is absurd. The apes have potent, accurate rifles; they are capable of quality machining, the kind that can only take place in the Industrial Age. Do Serling and Wilson truly expect me to believe that nobody in this thriving ape culture had ever thought of taking to the air, in, say, a balloon? Human, earth-bound aeronauts pre-date the Industrial Revolution by centuries. They might not have gotten far, but they certainly got up, and were intent on doing better.

There is another enormous, hard-to-swallow tripwire that’s positively embedded in Planet’s script, but to explore that would be to spoil the fun – dare I say the monkey business — so I shall leave that stone unturned. Instead, let’s focus on content.

Heston’s lost astronaut winds up on trial in an ape court, but really, it’s Serling putting humanity on trial. The ape prosecutor insists, “The Almighty created the ape in his own image…and set him apart from the beasts of the jungle, and made him the lord of the planet.” If the prosecutor is myopic, it is only in imitation of homo sapiens. Serling, and Planet, means to hold up a mirror to our own anthropocentrism — and though he does so blatantly, with more bludgeon than cunning, the baldness of the attack works. I cannot think of a film more willing to skewer blind belief.

ape prosecutor insists, “The Almighty created the ape in his own image…and set him apart from the beasts of the jungle, and made him the lord of the planet.” If the prosecutor is myopic, it is only in imitation of homo sapiens. Serling, and Planet, means to hold up a mirror to our own anthropocentrism — and though he does so blatantly, with more bludgeon than cunning, the baldness of the attack works. I cannot think of a film more willing to skewer blind belief.

Ours, that is.

Planet Of the Apes is an adventure flick, certainly, filled with plenty of chases, escapes, beatings, and gunfire trauma, but the film’s heart is politically charged and philosophical from the get-go, and it wears a liberal heart on its ragged, hairy sleeve. Planet posits that to repress knowledge or the seeking of it is inherently evil, and the action of Planet’s script is designed to underscore the point.

As such, the film functions as a humanist essay. It makes statements, stamps edicts, and preaches. The drama is, at rock bottom, nothing more than window-dressing, cover for a film that’s more message than movie. Plot, it seems, can indeed exist primarily as a disguise.

Luckily, this humble viewer likes the message, its we-are-flawed-but-trying optimism, so I was happy to put up with Planet’s more didactic asides.

Although the ending, I must admit, is anything but optimistic.

Should we then file Planet Of the Apes under the headings “Diversion,” “Curiosity,” and “Fad”?

I think not. A generation of kids may have been raised by these apes, but unlike Tarzan, we appear to have learned little from the experience. The movie makes a strong case for tolerance, flexible thinking, and a questioning spirit, but as I look around, especially in the direction of Washington D.C., I must conclude that we have not yet taken these lessons to heart. “Why must knowledge stand still?” asks one ape, just before the (famous) denouement. Good question, and one that ought to be asked of, among others, a good many of our elected representatives.

I think not. A generation of kids may have been raised by these apes, but unlike Tarzan, we appear to have learned little from the experience. The movie makes a strong case for tolerance, flexible thinking, and a questioning spirit, but as I look around, especially in the direction of Washington D.C., I must conclude that we have not yet taken these lessons to heart. “Why must knowledge stand still?” asks one ape, just before the (famous) denouement. Good question, and one that ought to be asked of, among others, a good many of our elected representatives.

And so it comes down to this: if we really want to solve budget crises, or anything else, I suggest we begin with a trip down memory lane, and mandatory viewings of Planet Of the Apes.

After all, we’re only human.

Now, I really must go. I may or may not be a higher life form, but I hear a local creek-bed calling my name. Time to build a dam — just for fun, mind — using nothing but stones, stone knives, and bearskins.

Ah, irony.

‘Til next time.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.”

Interesting overview. I hadn’t known Serling co-wrote the script. I’ve still never seen any of the films, although the PoA buzz still lingered when I was in grade school in the late ’70s. Eventually that was all but eradicated by the phenomenon that was Star Wars.

I am going to disagree with you about Heston. Now I am not going to say he was a great, or even a better than a good, actor. And I will admit he had the habit, like many actors do when they make it, of playing himself playing a role. But Taylor was perfect for Heston playing Heston playing Taylor. That makes the movie.

So, IMNSHO without Heston, PotA would have been forgotten long ago.

Nick – Judging by all the paraphernalia, I’d say P of A might deserve a re-examination as the blockbuster that busted blocks even before JAWS. But yes, STAR WARS certainly upped the ante.

TW – Great Scott, someone on this planet disagrees with me? Well, I suppose I’ll live. But! I do think that a number of better actors could have filled the role, and that it would have been a better film for it. Consider available leading men of the day like Steve McQueen, James Coburn, or Paul Newman. Consider the drive that George C. Scott could have provided. Or what about a Brit, maybe the young Michael Caine, or better yet, Peter O’Toole? I don’t in the least question that Heston’s imprint is all over the film, but I do not have any difficulty in picturing another actor taking on “George Taylor” and improving the role.

My two cents.

: )

Quit paying much attention after “execrable.” But de gustibus non est disputandum.

I doubt it would have been made without Heston and Edward G. Robinson appearing in the extended makeup test/screen test footage. That more or less sold it to Zanuck, along with a budget promise from Arthur P. Jacobs.

Heston, who I think very much deserved his Academy Award for Best Actor, is rather like Frank Sinatra. While there were better crooners out there, Sinatra had a way of phrasing a song that made it very much his own. Heston’s rather the same. Brando was probably the better screen actor of that generation, but with Heston, once he delivers a line it becomes his. I can’t say the same for much of Brando’s work, fine though it is (“Morituri” is one of the greatest war movies ever made and Brando’s forgotten gem).

Interestingly, Brando was the first choice of the production in the early stages. The production sketches based on Serling’s early script sure seemed to be Brandoesque.

While I think Stalag 17 would have been worse for Heston’s presence rather than Holden, I can’t think of anyone who would have made Planet of the Apes a better movie. Since Heston was instrumental in the choice of director Franklin J. Schaffner (they’d worked together in The Warlord) without Heston you’re getting into quite the alternate-universe Planet of the Apes.

This is one of my all-time favorite films, hands-down. However, I like the sequel BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES even better. Not that it’s a “better movie,” just that it hits my buttons harder than the first movie. BENEATH is a pure shot of pulp bravura which ends with the utter annihilation of planet earth at the hands of the bloody and dying Taylor. Part of the reason that BENEATH holds such a special place in my imagination is that it was the first movie I ever remember seeing in the theater–I was 5 years old when I witnessed the mutants of the undercity pulling their flesh-masks off to reveal their true selves to their god–the cobalt bomb.

For anybody who’s interested, and who might have missed it the first time around, I did a big BG post on BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES right here: http://www.blackgate.com/2011/07/23/glory-be-to-the-bomb-and-to-the-holy-fallout/

Hi Eric – I’m so sorry you stopped reading! Most of the post has very little to do with Heston. Also, I concur with you about the Robinson screen test. I hope you’ll change your mind and backtrack…

John – I’ve never seen BENEATH. Now I want to. Thanks for giving that film a shout-out, and for the link.

A confession: all this talk of apes is going to send me straight to my CD shelves for a listen to that seminal Kinks classic, “Ape Man.”

Mark: Really? Ah, I feel like my good deed of the week is done–getting someone who has never seen it to watch BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES. Thanks!

PS. The PLANET OF THE APES TV show is also available on DVD. It’s quite entertaining, although limited by the standards of 70s TV, but it was miles above most other shows of the time (except KUNG FU). The writing was solid and the actors were incredibly likable–especially Roddy McDowall, who played Cornelius and Ceasar in the movies, and who stars in the TV series as Galen. Ah, childhood memories. I even dig the PotA cartoon that began when the live-action series ended.

Oh, I read the whole thing, my brain just switched over from scholarly interest to light reading.

Fultz, I’m not that big a fan of Beneath. It’s certainly watchable, but a bit too much of it is repeating the thrills of the first. But you are right, once we get into ruined New York and Talor shows up again, it goes very dark very fast. Talk about knocking the audience around!

The fourth, Conquest, is my second fave after the near-perfect first.

The fifth, Battle, was the first I remember seeing in the theater (well, a drive-in, dressed in my Spider Man PJs) as a squirt. I’d seen some of the others on TV and mostly remember being confused.

To this day Battle frustrates me, because there are nuggets of such a good story in there that really aren’t fleshed out. And the “Battle” is just makes me sad. I think the MASH tv series had more spectacular battle footage. But back to the story: has the timeline truly been diverted, because Cornelius’s backstory from Escape is now changed? They could have done more with Alto, maybe suggesting that he was re-wwriting ape history in a Stalinesque fashion.

BATTLE (the fifth movie) is my second-favorite sequel, coming in right after BENEATH. In my opinion (and that’s all it is), the weakest movies are ESCAPE (#3) and CONQUEST (#4)–but that said, I actually like ALL the APES movies. I’m just ranking my love of the sequels. The best thing about BATTLE is the incredible “melted” city that Ceasar, Virgil, and their human friend explore. It’s helps to remember that, when it comes to the sequels, each successive movie was made for HALF of what the previous movie was made for. That means by the time they got to BATTLE, it was made on a shoestring budget, which explains why the final “battle” wasn’t that grand of an affair. Still, it’s a classic moment when Caesar unveils his gambit, screaming “Up! Up! And fight like apes!!!” I also love the “Ape shall not kill Ape” plotline. But my favorite bits from BATTLE are the wise Orangutans, specifically Virgil, who theorizes about time travel and delivers some truly great lines about mankind/apekind and the cyclical nature of violence.

Finally, yes, I think that after the destruction of the earth in #2, Ceasar’s story is indeed an alternate timeline that begins in ESCAPE, continues through CONQUEST, and runs right into BATTLE.

I’m really hoping the new franchise continues doing a good job of creating a more logical and consistent timeline…I hope DAWN OF THE PLANET OF APES hearkens more to the “western-style” adventure of the first movie.