A review of The Door Into Fire by Diane Duane

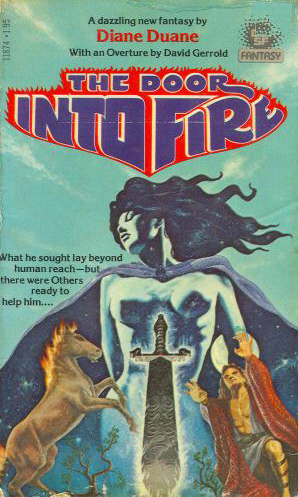

The Door Into Fire, by Diane Duane

The Door Into Fire, by Diane Duane

Dell Fantasy (304 pages, $1.95, 1979)

Prince Herewiss of the Brightwood has two major problems.

First, he’s the first man in generations to have the Flame, a form of energy that’s much more potent than ordinary sorcery — but he can’t use it at all if he can’t make a physical focus with which to channel it.

His other problem is his lover Freelorn, exiled Prince of Arlen and trouble magnet. The summary on the back of The Door Into Fire refers to Freelorn as Herewiss’s “dearest friend” — which, in my opinion, does the book a disservice.

The Door Into Fire is about magic power, overcoming old tragedies, and the beginning of an epic kingdom-changing quest. It’s about a very hands-on Goddess and how she deals with her creation.

But it’s also about sex. Sex and love, sex and jealousy, sex in a culture where bisexuality and polyamory seem to be the default — sex that starts from a different set of assumptions than the average American reader carries around.

Check out

Check out  In a post on his blog last week, Canadian science fiction author Robert Sawyer asked “

In a post on his blog last week, Canadian science fiction author Robert Sawyer asked “

Confession: I am a fan of pulp fantasy who has, until recently, read very little Clark Ashton Smith. Yes, the man who comprises one of the equilateral sides of the immortal Weird Tales triangle has largely eluded me, save for a few scattered tales and poems I’ve encountered in sundry anthologies and websites.

Confession: I am a fan of pulp fantasy who has, until recently, read very little Clark Ashton Smith. Yes, the man who comprises one of the equilateral sides of the immortal Weird Tales triangle has largely eluded me, save for a few scattered tales and poems I’ve encountered in sundry anthologies and websites. “Utter originality is, of course, out of the question.”

“Utter originality is, of course, out of the question.” “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

“You’re gonna need a bigger boat.” Over at Tor.com, bloggers Bill Capossere and Amanda Rutter have commenced an epic re-read of all ten volumes of The Malazan Book of the Fallen, starting with the first novel, Gardens of the Moon.

Over at Tor.com, bloggers Bill Capossere and Amanda Rutter have commenced an epic re-read of all ten volumes of The Malazan Book of the Fallen, starting with the first novel, Gardens of the Moon. I’ve discovered that once you start writing about 1930s magazine science fiction — a field small enough for thorough analysis, but bursting with enough wonders to fill the galaxy — it becomes difficult to stop. Pondering the marvels of

I’ve discovered that once you start writing about 1930s magazine science fiction — a field small enough for thorough analysis, but bursting with enough wonders to fill the galaxy — it becomes difficult to stop. Pondering the marvels of  I have a habit of buying books — a compulsion, really. Older books, mostly, from book fairs and small used bookstores. Things that look unusual, and which, in the absence of an immediate reason on my part to read them immediately, often sit on my shelves for some time before I get around to them.

I have a habit of buying books — a compulsion, really. Older books, mostly, from book fairs and small used bookstores. Things that look unusual, and which, in the absence of an immediate reason on my part to read them immediately, often sit on my shelves for some time before I get around to them.