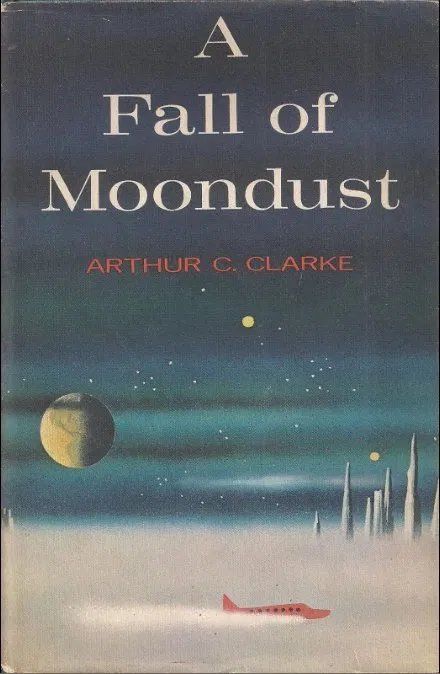

Arthur C. Clarke on the Moon: A Fall of Moondust and Earthlight

A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke; First Edition: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962.

Cover art Arthur Hawkins. (Click to enlarge)

A Fall of Moondust

by Arthur C. Clarke

Harcourt, Brace & World (248 pages, $3.95 hardcover, 1962)

Cover art by Arthur Hawkins

Earthlight

by Arthur C. Clarke

Ballantine (186 pages, $2.75 hardcover, 1955)

Cover art by Richard Powers

Arthur C. Clarke is best known for his visionary, philosophical tales of human destiny, with their explorations of the depths of time and space, their brushing contact with godlike aliens: Childhood’s End, The City and the Stars, “The Star,” “The Nine Billion Names of God,” and of course 2001: A Space Odyssey. But another type of story turns up regularly throughout his career: the near-term technological puzzle story. Prelude to Space (covered here) has its philosophical overtones, but is basically about the technical and political issues of launching a rocket to the moon. And of course the center section of 2001 is all about diagnosing a malfunctioning part, and dealing with a malfunctioning supercomputer. Famous early stories like “Technical Error” and “Superiority” dealt with issues of problematic future technology.

Clarke’s 1962 novel A Fall of Moondust is very much a story of technical problems and how they are solved (and the resolution is a happier one than those in the other titles just mentioned). Specifically, it’s about a search and rescue mission, anticipating the spate of “disaster” movies (and associated novels) about groups of civilians trapped in some situation (burning skyscraper, disabled passenger jet, and so on) and the parallel efforts of rescuers to save them, that were popular especially in the ‘70s. (In fact, Wikipedia notes this novel’s similarity to a 1978 film about a stranded submarine, Gray Lady Down.)

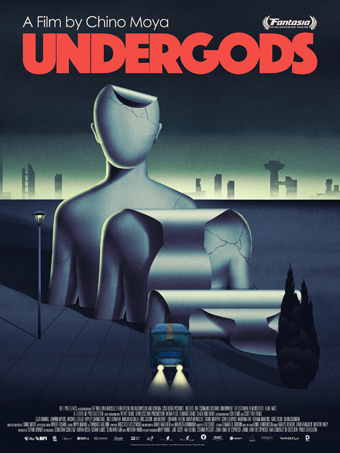

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

There’s an old line that says science fiction literalises metaphors. It’s a line that applies to fantasy and horror, too. It means that, for example, a realist book may say that somebody walking through their old house is haunted by memories like the ghosts of their past, while a horror story might have that person be actually haunted by an actual ghost representing that past. What is metaphor in one case is literal in the other. But still a metaphor, as well, still symbolising something more than itself. Part of the trick of writing stories of the fantastic is knowing how to handle the metaphorical and the literal — knowing exactly how literal to make the literalised metaphor, and how to explore what literalising the metaphor brings the story, and how to explore the metaphor as metaphor while keeping it a literal thing.

There’s an old line that says science fiction literalises metaphors. It’s a line that applies to fantasy and horror, too. It means that, for example, a realist book may say that somebody walking through their old house is haunted by memories like the ghosts of their past, while a horror story might have that person be actually haunted by an actual ghost representing that past. What is metaphor in one case is literal in the other. But still a metaphor, as well, still symbolising something more than itself. Part of the trick of writing stories of the fantastic is knowing how to handle the metaphorical and the literal — knowing exactly how literal to make the literalised metaphor, and how to explore what literalising the metaphor brings the story, and how to explore the metaphor as metaphor while keeping it a literal thing.

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

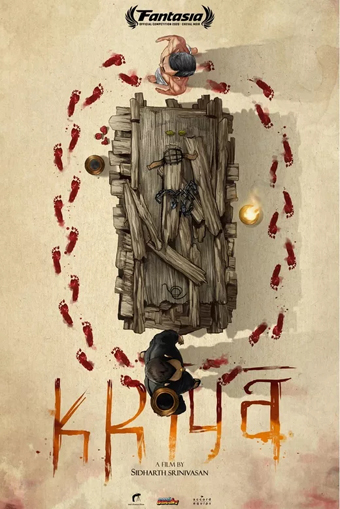

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.