Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: “When the Levee Breaks (and the Goddess Wakes), I’ll Have a Place to Stay…”

|

|

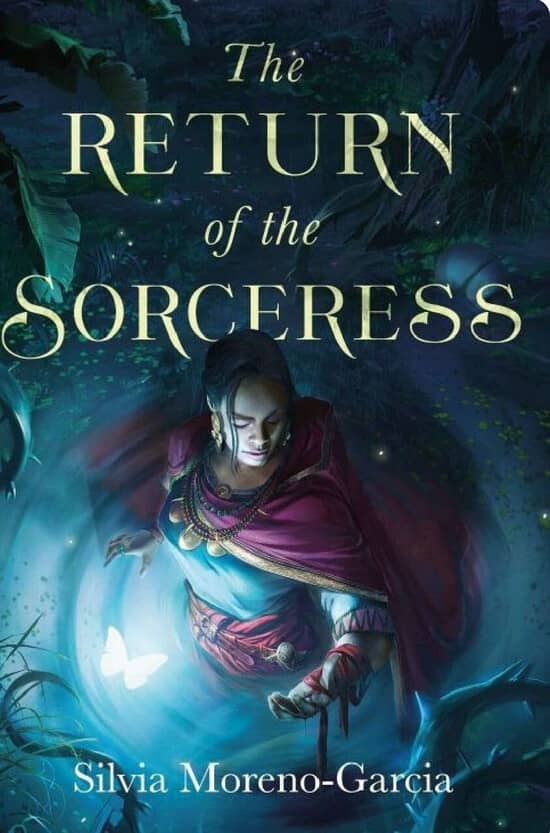

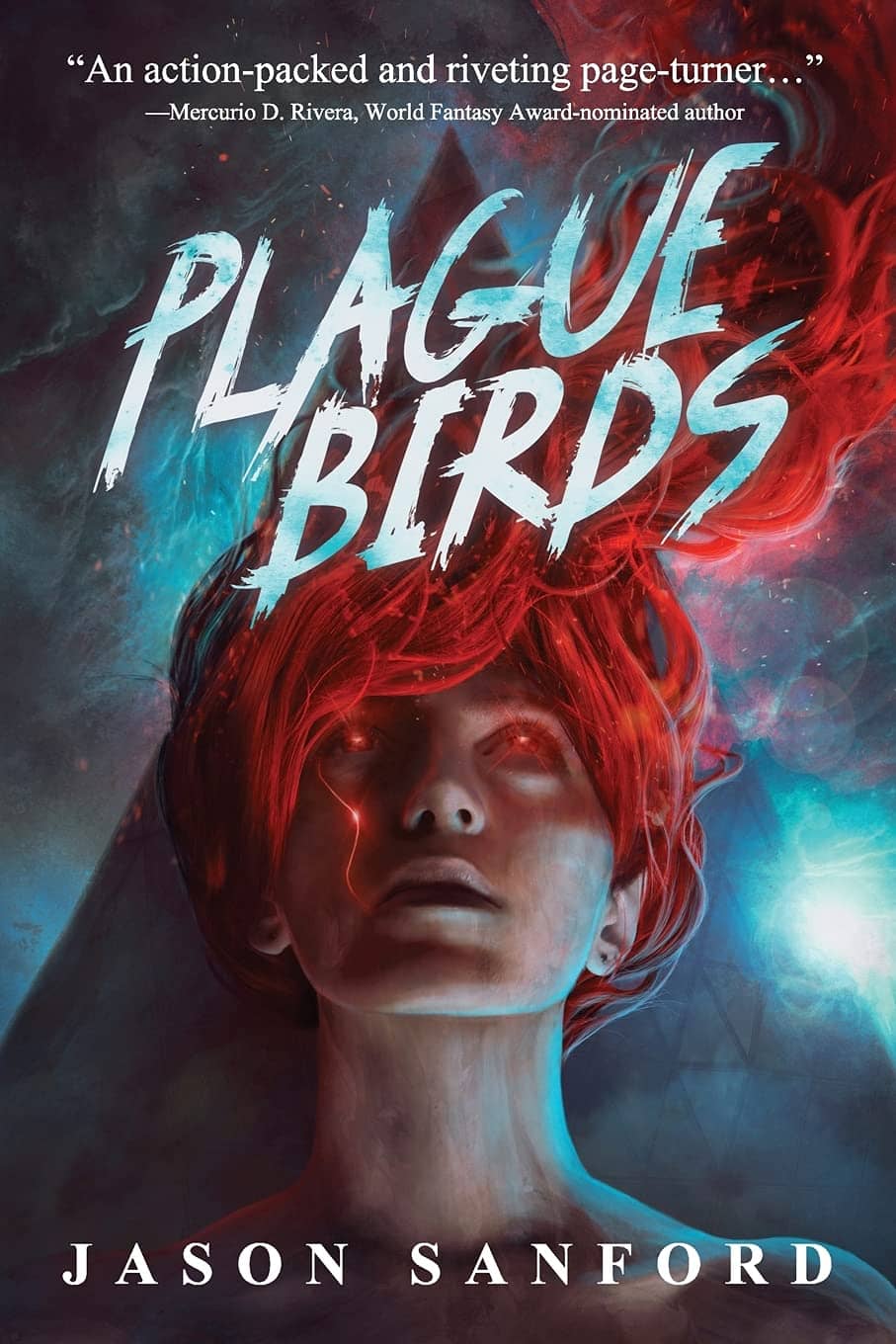

When the Goddess Wakes (St. Martin’s Press, August 2021). Cover by Lauren Saint-Onge

Know, O prince, that between the years when Stag-flation and the Iran Hostage Crisis drank the Carter Administration, and the years of the rise of the stepson of Roger Clinton Sr, there was an Age Undreamed of, when sword & sorcery, high fantasy epics, slender trilogies and stand-alone novels lay spread across bookshelves like paper jewels beneath fluorescent stars.

This tongue-in-cheek riff on Robert E. Howard’s famous quote from the Nemedian Chronicles is a perfect way to begin a review of Howard Andrew Jones’s concluding volume of the Ring Sworn Trilogy, because it is both a very modern fantasy, and yet, in so many ways the product of growing up as a fantasy-reading GenXer – which both Jones and I are.

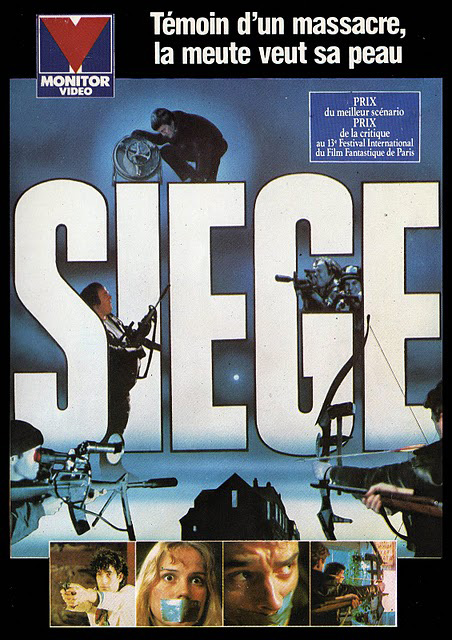

You ever watch one of the long video game cutscenes that passes for movies these days and think “I kinda miss old, raw-looking films, like early Romero and Carpenter. Something that had teeth. Heart. Balls. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”

You ever watch one of the long video game cutscenes that passes for movies these days and think “I kinda miss old, raw-looking films, like early Romero and Carpenter. Something that had teeth. Heart. Balls. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”