English Gothic: Britain Goes to the Movies

Jonathan Rigby’s ENGLISH GOTHIC (2000) is an excellent survey of British horror and science fiction films. Misleadingly subtitled A CENTURY OF HORROR CINEMA; the book focuses instead on the 20 year period from THE QUATERMASS XPERIMENT (1955) through TO THE DEVIL, A DAUGHTER (1976) when British production companies like Hammer, Amicus, and Tigon consistently outperformed the Hollywood majors in producing the finest and most influential genre films.

Jonathan Rigby’s ENGLISH GOTHIC (2000) is an excellent survey of British horror and science fiction films. Misleadingly subtitled A CENTURY OF HORROR CINEMA; the book focuses instead on the 20 year period from THE QUATERMASS XPERIMENT (1955) through TO THE DEVIL, A DAUGHTER (1976) when British production companies like Hammer, Amicus, and Tigon consistently outperformed the Hollywood majors in producing the finest and most influential genre films.

Part of the book’s strength is not just Rigby’s detailed and chronological survey of nearly every genre film to come from the British Isles during these two decades, but the fact that he captures the social and economic factors that helped shape the pictures and, more importantly, the public’s reception to them.

The rise of the horror genre in film started with the German Expressionist classics of the silent era and the contemporary Lon Chaney and John Barrymore efforts in the States. The genre solidified with the phenomenal impact of Universal’s horror franchises of the 1930s and 1940s.

The interesting thing here is that the majority of these films remained unscreened or else limited to adult-only audiences in the UK where censorship was extremely puritanical in the first half of the last century.

The unfortunately named Bull Spec (I’m assuming this is a reference to Bull Durham tobacco and/or the Kevin Costner movie that takes place in Durham, N.C. where the magazine is based and its intent to feature local writers of “speculative fiction”) has published its

The unfortunately named Bull Spec (I’m assuming this is a reference to Bull Durham tobacco and/or the Kevin Costner movie that takes place in Durham, N.C. where the magazine is based and its intent to feature local writers of “speculative fiction”) has published its

Steve is a very normal man, perhaps even a bit boring. He works at an English shipping company, handling inventories and looking forward to a career in politics once he climbs the business ladder as far as it will take him. One day, for no particular reason, a sudden fit of discontent sends him down to the docks looking for something different, perhaps a restaurant he hasn’t visited. In an alley, he sees a man being attacked . . .

Steve is a very normal man, perhaps even a bit boring. He works at an English shipping company, handling inventories and looking forward to a career in politics once he climbs the business ladder as far as it will take him. One day, for no particular reason, a sudden fit of discontent sends him down to the docks looking for something different, perhaps a restaurant he hasn’t visited. In an alley, he sees a man being attacked . . . Early on in this film we see Bruce Willis with hair and looking young, and not Die-Hard bashed up, and we wonder absently if this time he’ll actually finish the film as scar-free as he began it. The Willis we begin with is quickly established as a ‘surrogate,’ the robot avatar of the real Willis character, Tom Greer, and it doesn’t take long for both Greer and his surrogate to get bashed up in familiar form.

Early on in this film we see Bruce Willis with hair and looking young, and not Die-Hard bashed up, and we wonder absently if this time he’ll actually finish the film as scar-free as he began it. The Willis we begin with is quickly established as a ‘surrogate,’ the robot avatar of the real Willis character, Tom Greer, and it doesn’t take long for both Greer and his surrogate to get bashed up in familiar form. “Imagine if Frodo had died during his journey and the One Ring had returned to Sauron.”

“Imagine if Frodo had died during his journey and the One Ring had returned to Sauron.” Am I a bad gamer if I really, really want to play this game?

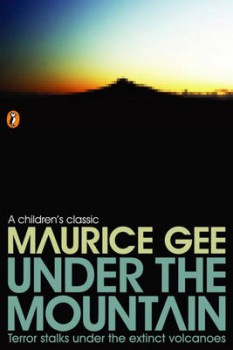

Am I a bad gamer if I really, really want to play this game? Under the Mountain (1979)

Under the Mountain (1979)