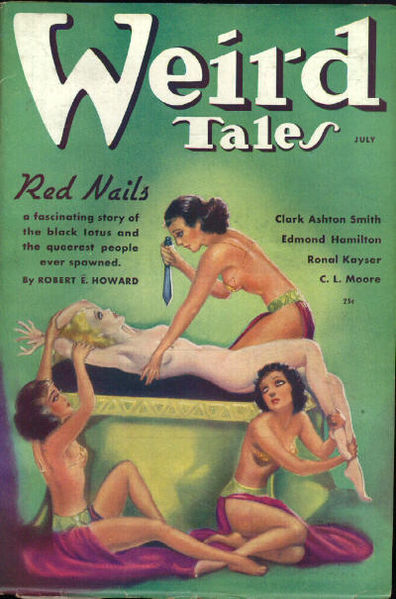

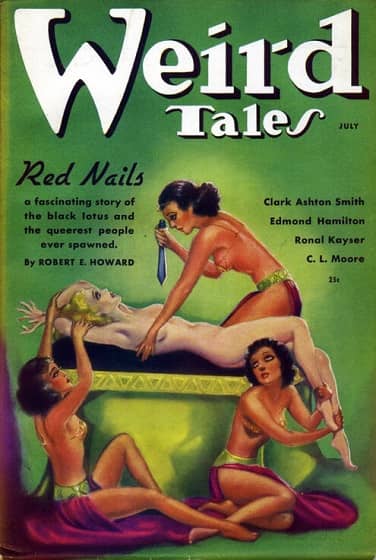

Weird Tales Deep Read: July 1936

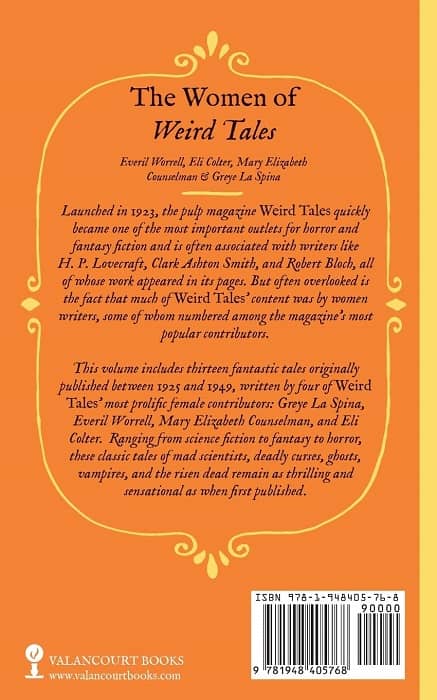

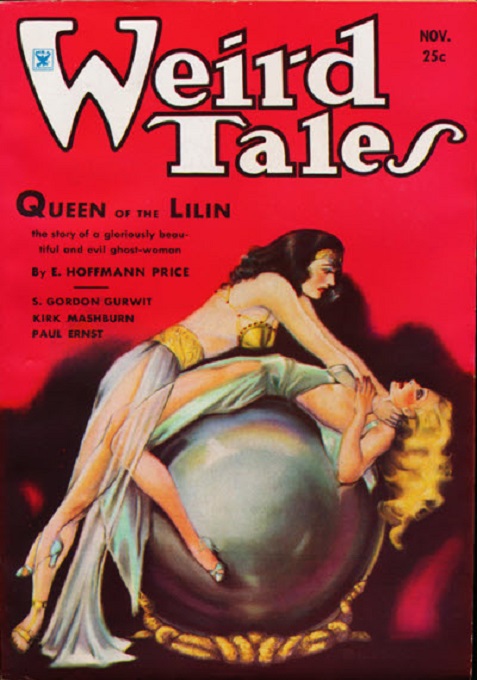

Margaret Brundage for Red Nails

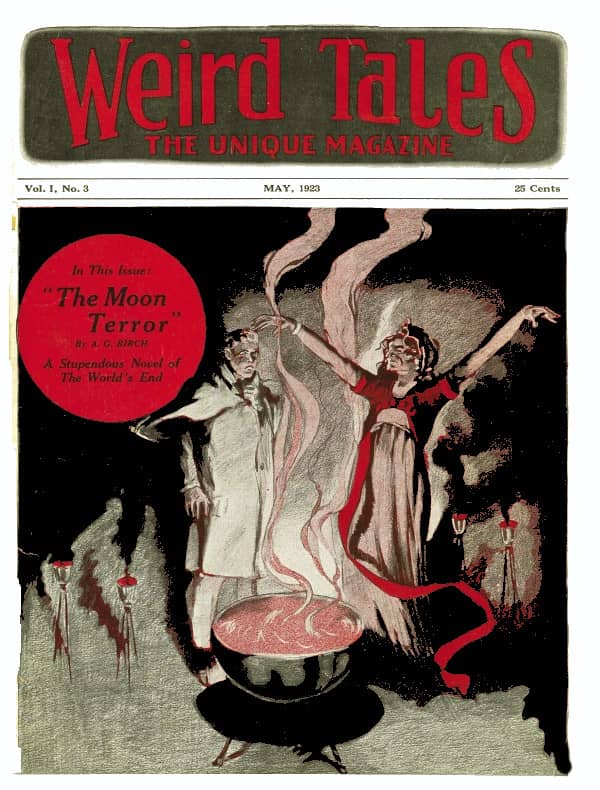

We return to the golden age of Weird Tales to consider the eleven stories in the July 1936 issue. This time around we’re dealing with many familiar authors, led by the triumvirate of C. L. Moore, Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard, one H. P. Lovecraft short of perfection. The big three present classic tales from their popular fantasy series (Northwest Smith, Zothique, Conan). The other familiar names deliver more of a mixed bag, but for the most part come through with decent offerings.

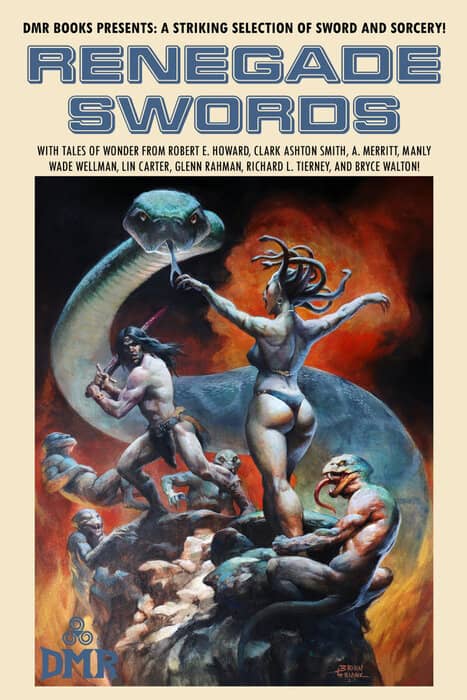

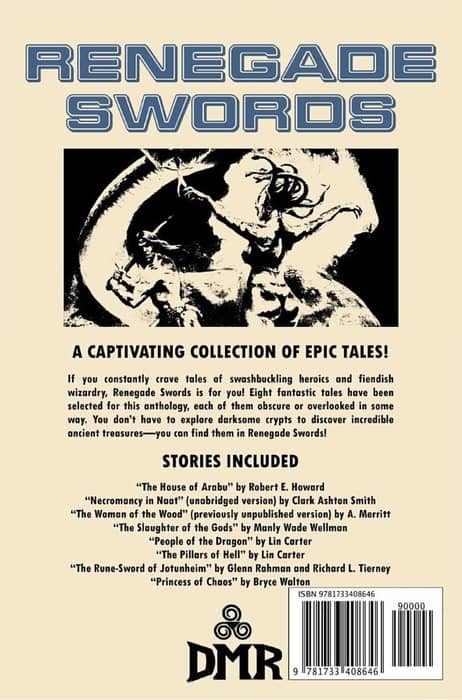

Edmond Hamilton, a prolific pulpster for WT and countless other genre magazines contributes one of his weakest efforts in a tale concerning germs from space. The August Derleth and Manly Wade Wellman stories are both decent, if slight, and the Arthur Conan Doyle reprint, for a change, rises above the level of curiosity.

Of the eleven stories, seven are contemporary (64%), three are set in the future (27%), and one in the past (9%), though it’s a little complicated because two stories use framing devices that cut across temporal periods. Six take place in the United States (55%), one starts in the US then goes off on a round the world tour (9%), two are in fictitious realms (18%), one in France (9%), and one on the Moon (9%).