The Nightmare Men: “The Supernatural Sleuth”

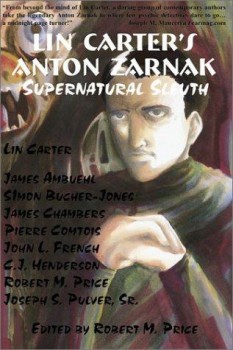

Lin Carter’s Anton Zarnak is a man of mystery. With a jagged streak of silver running through his black hair from his temple to the base of his skull and his exotic features and peculiar mannerisms, Zarnak is almost as outré as the enemies he fights. With a startling knowledge and a somewhat sinister history, Zarnak battled evil in three stories penned by Carter — “Curse of the Black Pharaoh”, “Dead of Night”, and “Perchance to Dream” — as well as in a half dozen or so more contributed by the likes of Robert M. Price, CJ Henderson, Joseph S. Pulver Sr. And James Chambers. All of these stories, for those interested, are collected in Lin Carter’s Anton Zarnak: Supernatural Sleuth from Marietta Publishing.

Lin Carter’s Anton Zarnak is a man of mystery. With a jagged streak of silver running through his black hair from his temple to the base of his skull and his exotic features and peculiar mannerisms, Zarnak is almost as outré as the enemies he fights. With a startling knowledge and a somewhat sinister history, Zarnak battled evil in three stories penned by Carter — “Curse of the Black Pharaoh”, “Dead of Night”, and “Perchance to Dream” — as well as in a half dozen or so more contributed by the likes of Robert M. Price, CJ Henderson, Joseph S. Pulver Sr. And James Chambers. All of these stories, for those interested, are collected in Lin Carter’s Anton Zarnak: Supernatural Sleuth from Marietta Publishing.

Like the pulp characters Carter based him on, Zarnak is something of a Renaissance man. Educated at a number of prestigious universities, including the Heidelberg (where he studied theology with a certain Anton Phibes, according to “The Case of the Curiously Competent Conjurer” by James Ambuehl and Simon Bucher-Jones), the Sorbonne and Miskatonic University, he is an accredited physician, musician, theologian and metaphysicist. He speaks eleven languages and has one of the finest and most complete collections of occult literature in existence. His home drifts like a soap bubble between Half-Moon Street in London, No. 13 China Alley in San Francisco and a cursed apartment building in New York; always decorated in oriental splendour, it is filled to bursting with esoteric paraphernalia, including a hideously decorated mask of Yama which always hangs in a place of honour above Zarnak’s desk.

And, as the saying goes, ‘so a man’s home, his mind’ — Zarnak is the proverbial odd duck. By turns consoling and caustic, arrogant and affectionate, and almost inhumanly ruthless, Zarnak is no comforting Judge Pursuivant or soothing John Silence. He is singularly and irrepressibly Zarnak.

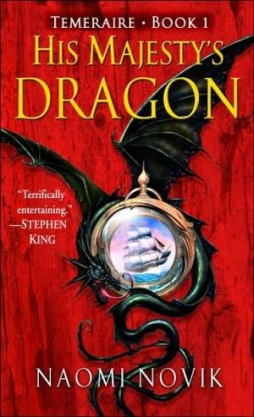

I’ve been in unwilling low-content mode for the past couple of weeks (question: what’s worse than getting the flu at Christmas? Answer: getting the flu along with a sinus infection). That’s meant I’ve had some time to read, which is good for a number of reasons. As it happens, though, one of the things I picked up to read left me wondering something I’ve wondered several times before: why do certain books pull me along, and compel me to read them, even when I think they’re not particularly good?

I’ve been in unwilling low-content mode for the past couple of weeks (question: what’s worse than getting the flu at Christmas? Answer: getting the flu along with a sinus infection). That’s meant I’ve had some time to read, which is good for a number of reasons. As it happens, though, one of the things I picked up to read left me wondering something I’ve wondered several times before: why do certain books pull me along, and compel me to read them, even when I think they’re not particularly good? There are two different stories about how it began.

There are two different stories about how it began. I’ve been a bit under the weather the past couple of weeks, which has been annoying for a number of reasons. For one thing, I was unable to get my thoughts in enough order to respond adequately to three pieces of writing I came across several days ago. Each piece on its own seemed to pose interesting questions, and collectively they raised what seemed to me to be related issues about how one reads, and why; and how and why one reads fantasy in particular.

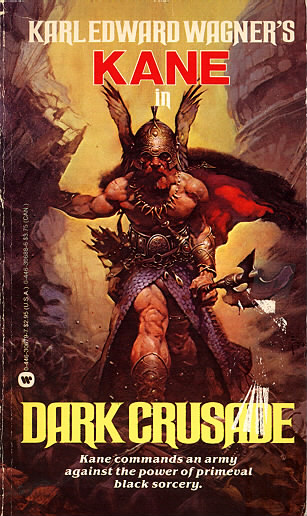

I’ve been a bit under the weather the past couple of weeks, which has been annoying for a number of reasons. For one thing, I was unable to get my thoughts in enough order to respond adequately to three pieces of writing I came across several days ago. Each piece on its own seemed to pose interesting questions, and collectively they raised what seemed to me to be related issues about how one reads, and why; and how and why one reads fantasy in particular. Why has swords and sorcery languished while epic fantasy enjoys a wide readership? In an age of diminished attention spans and the proliferation of Twitter and video games, it’s hard to explain why ponderous five and seven and 12 book series dominate fantasy fiction while lean and mean swords and sorcery short stories and novels struggle to find markets (Black Gate and a few other outlets excepted).

Why has swords and sorcery languished while epic fantasy enjoys a wide readership? In an age of diminished attention spans and the proliferation of Twitter and video games, it’s hard to explain why ponderous five and seven and 12 book series dominate fantasy fiction while lean and mean swords and sorcery short stories and novels struggle to find markets (Black Gate and a few other outlets excepted). Warning: Some spoilers follow

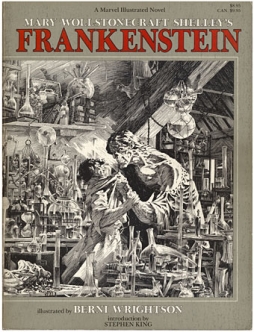

Warning: Some spoilers follow This is the fifth in an ongoing series of posts about Romanticism and the development of fantasy fiction; you can find previous installments

This is the fifth in an ongoing series of posts about Romanticism and the development of fantasy fiction; you can find previous installments  This is the latest in a series of posts about Romanticism and the development of fantasy. You can find prior posts

This is the latest in a series of posts about Romanticism and the development of fantasy. You can find prior posts  In my

In my  A man of great height and greater girth, Judge Keith Hilary Pursuivant, after retiring from the bench, devoted his golden years to investigating the occult in the works of North Carolina author,

A man of great height and greater girth, Judge Keith Hilary Pursuivant, after retiring from the bench, devoted his golden years to investigating the occult in the works of North Carolina author,