Dorgo the Dowser and Me

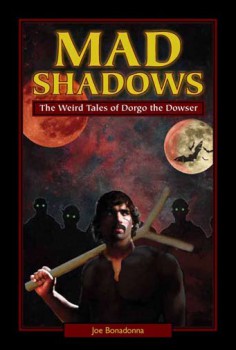

When John O’Neill invited me to write article about my collection of sword and sorcery stories, Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser, for the Black Gate blog, I was naturally thrilled and honored. I was also somewhat uncertain.

When John O’Neill invited me to write article about my collection of sword and sorcery stories, Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser, for the Black Gate blog, I was naturally thrilled and honored. I was also somewhat uncertain.

Where do I begin? What should I say?

So I asked myself… why not first tell readers something about your book — the world of Tanyime, the kingdom of Rojahndria, the city of Valdar, and its main character — and then talk a little bit about how it all came to be? Well, here goes.

Mad Shadows is a picaresque novel — six interconnected sword and sorcery tales featuring Dorgo the Dowser, a sort of private eye set in the 14thcentury of my alternate world. It is pulp-fiction, old-school sword and sorcery with a film noir twist. That’s one of the reasons for the subtitle, The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser, and the retro look of the cover.

One reason of the reasons Dorgo is known as the Dowser is because he’s a sort of private investigator, searching for clues and answers like someone searching for water with a dowsing rod. The other reason for his epithet is that he actually uses a special kind of dowsing rod in his line of work. There are all kinds of dowsing tools, and each has its own special use or “power.” I even think that dowsing rods may be the inspiration for what we call “magic wands.”

Scott Westerfeld has posted on his blog

Scott Westerfeld has posted on his blog

I recently

I recently