Birthday Reviews: John Langan’s “The Unbearable Proximity of Mr. Dunn’s Balloons”

John Langan was born on July 6, 1969.

Langan’s novel The Fisherman received the Bram Stoker Award for Best Novel. His earlier collection Mr. Gaunt and Other Uneasy Encounters was also nominated for the award. The story version of “Mr. Gaunt” as well as his story “On Skua Island,” were both nominated for the International Horror Guild Award. Langan serves on the Board of Directors for the Shirley Jackson Award.

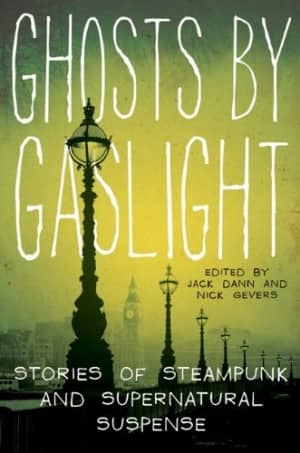

He wrote “The Unbearable Proximity of Mr. Dunn’s Balloons” for Jack Dann and Nick Gevers for the anthology Ghosts by Gaslight. Published in 2011, the story has never been reprinted.

“The Unbearable Proximity of Mr. Dunn’s Balloons” is the story of Mark Stephen Chapman, an author who has arranged to spend the summer at the home of Parrish Dunn, a spiritualist whose home, and especially the strange balloons he decorates it with, are intriguing to Chapman. On his way up to Dunn’s estate, Chapman meets Cal and Isabelle Earnshaw, who are also on their way to spend time with Dunn. Cal is dying and has hopes that Dunn can ease his passage.

The majority of the story is told as a series of conversations between Isabelle and Chapman, although occasionally Langan includes a page from Chapman’s journals, as Chapman shared much about his past with Isabelle. Chapman also talks about his life with Cal, who regrets not having lived the full life he sees Chapman as having had. The most enigmatic of the characters is Dunn, who appears occasionally, but rarely interacts with Chapman until the story’s denouement.

Until the end of the story, there is little fantastic that occurs. Dunn’s treatment of Cal and Cal’s response are all physical in nature, whether or not Dunn is an actual spiritualist or a charlatan. Chapman never really develops a relationship with Dunn and finds himself uncomfortable around the paper balloons. Eventually, when Isabelle decides she wants to take Cal away from Dunn, Chapman serves to distract him and learns the truth about Dunn’s balloons and why they are so disturbing, although Langan does not indicate why others have not felt the same concern about them.