Telling a Clock What You Want to Eat

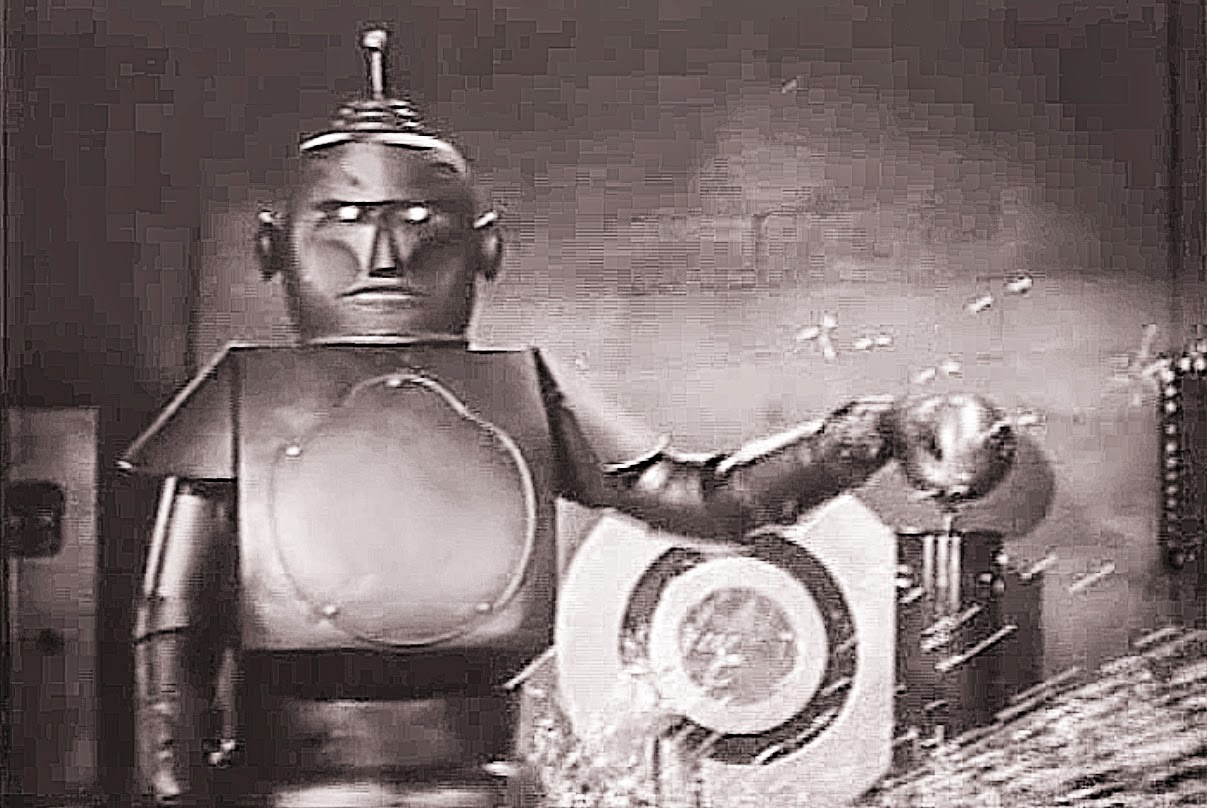

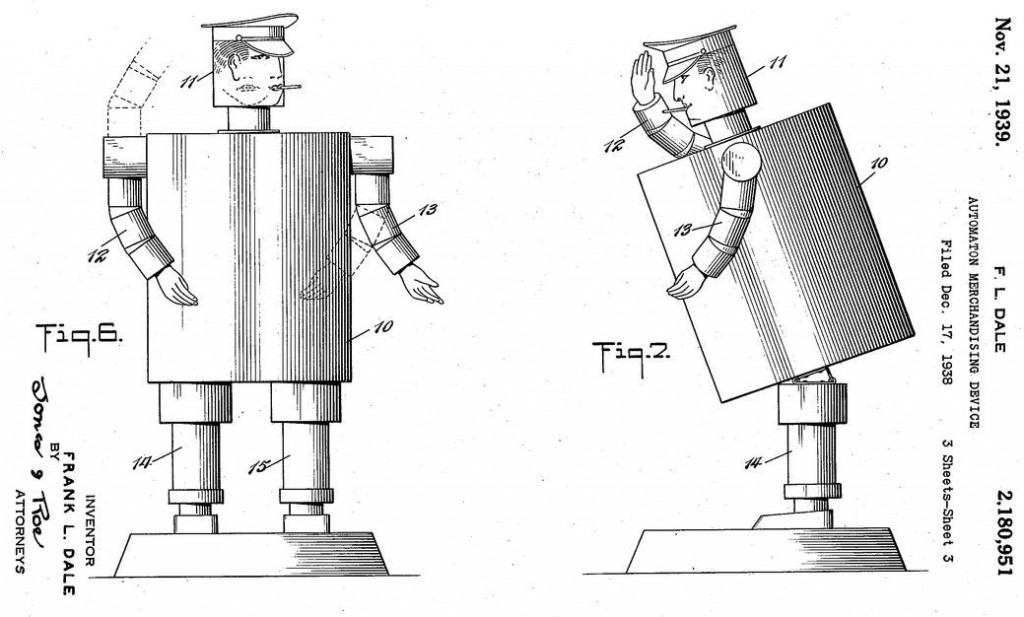

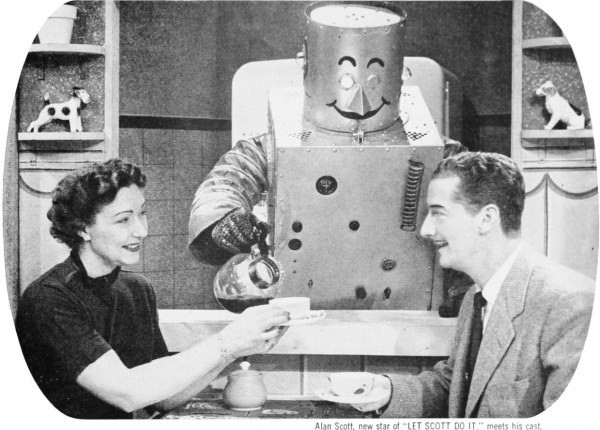

Long before Karel Čapek introduced the word “robot” to the general vocabulary in his 1920 play R.U.R., people had a pretty good idea of what an “automaton” or a “mechanical man” did. They learned it from popular media. Short stories, newspaper articles, vaudeville acts, comic strips, and more toyed with the idea of humanoid mechanical servants.

Or non-humanoid one. It took a very long time for the concept of “robot” to coalesce around the human form. Not until after World War II did a robot automatically conjure an image of a mechanical human, and that was largely because a word was needed to separate robots from the computer brains that increasingly took the robot’s place in media.

Before WWII, in fact, robot was frequently applied to any automatic machine which functioned with constant human supervision. Before R.U.R. mechanical man or automaton did much the same.

When a completely automated hotel was proposed, in Paris in 1913, the natural way to explain its operation was to use on these terms.

[T]o get the highest efficiency at the lowest cost … can be effected … by the “mechanical man” in the hotel – the “man” who is prompt in action, above all, and is absolutely dependable, deft, noiseless and invisible.