Novel Writing: The Hard Part

As I write this, I’m closing in on the 50,000 word mark of my NaNoWriMo novel. I’m aiming for 100,000 words, which means I’m well behind my ideal pace, but if I can keep going for 6,000 words a day over the next week and a half, I should get there. So it’s still very possible. (You can read some thoughts on National Novel Writing Month here, some talk about the Arthurian legends that inspired my plot here, and a more detailed discussion of my plans over here.)

As I write this, I’m closing in on the 50,000 word mark of my NaNoWriMo novel. I’m aiming for 100,000 words, which means I’m well behind my ideal pace, but if I can keep going for 6,000 words a day over the next week and a half, I should get there. So it’s still very possible. (You can read some thoughts on National Novel Writing Month here, some talk about the Arthurian legends that inspired my plot here, and a more detailed discussion of my plans over here.)

An outside observer might wonder what the point is. The book I write isn’t going to be very good; it’s a first draft, written in haste. Why not take it slower, and produce something better? But whatever I’d write would have to be reworked; that’s the way of things. Still, even assuming that this particular way of working is conducive to eventually producing something worthwhile … well, what is it that’s worthwhile, exactly? What, in short, is the point of writing this novel?

I don’t know if there’s really an answer to that. But why ask the question at all?

Only because that’s where I’m at with the novel.

Tonight, children go trick-or-treating, and many adults go to Halloween parties, thereby, perhaps, proving Ogden Nash’s line that children get more joy out of childhood than adults get out of adultery. For myself, though, I’ll be counting down the minutes to midnight, scrawling notes and making plans. Because at 12 AM, November 1,

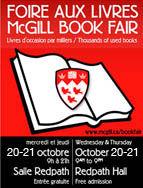

Tonight, children go trick-or-treating, and many adults go to Halloween parties, thereby, perhaps, proving Ogden Nash’s line that children get more joy out of childhood than adults get out of adultery. For myself, though, I’ll be counting down the minutes to midnight, scrawling notes and making plans. Because at 12 AM, November 1,  The McGill book fair is the largest English-language used book sale in Montreal. It’s been held for decades, every October, on the second Wednesday and Thursday after Thanksgiving (which in Canada is on the second Monday in October). Every year an eclectic mix of thousands of books are sold, helping to raise money for scholarships.

The McGill book fair is the largest English-language used book sale in Montreal. It’s been held for decades, every October, on the second Wednesday and Thursday after Thanksgiving (which in Canada is on the second Monday in October). Every year an eclectic mix of thousands of books are sold, helping to raise money for scholarships.

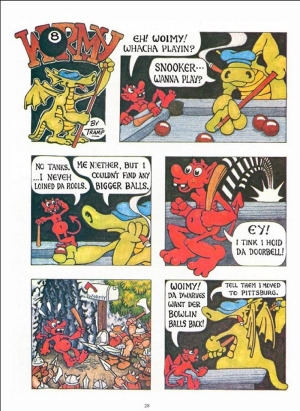

It begins with an imp, some dwarves, a stolen set of bowling balls, and a cigar-smoking dragon in a flat newsboy cap. It gets stranger from there, sprawling through an epic of long-jawed mudsuckers, oddly literate stonedrakes, bad puns, bounty hunters, and some of the most spectacular color comics pages you can imagine.

It begins with an imp, some dwarves, a stolen set of bowling balls, and a cigar-smoking dragon in a flat newsboy cap. It gets stranger from there, sprawling through an epic of long-jawed mudsuckers, oddly literate stonedrakes, bad puns, bounty hunters, and some of the most spectacular color comics pages you can imagine. In one of my first posts here, I mentioned that I was hoping to figure out what it is, exactly, that I like about fantasy fiction; what it is I get from fantasy that I get nowhere else.

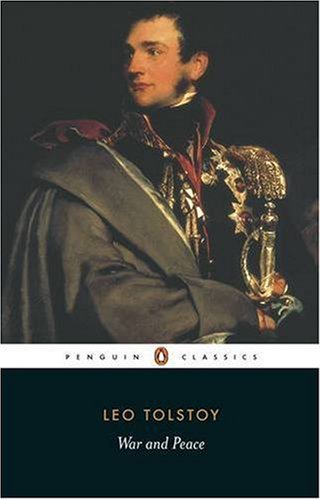

In one of my first posts here, I mentioned that I was hoping to figure out what it is, exactly, that I like about fantasy fiction; what it is I get from fantasy that I get nowhere else. One of the characteristics of a great book is that you can go back to it at different times in your life and get different things out of it. But then sometimes the reverse happens: you read a book before you’re ready. If you’re lucky, though, the book hangs around in the back of your mind, and eventually you pick it up again and find out what you weren’t able to grasp the first time around.

One of the characteristics of a great book is that you can go back to it at different times in your life and get different things out of it. But then sometimes the reverse happens: you read a book before you’re ready. If you’re lucky, though, the book hangs around in the back of your mind, and eventually you pick it up again and find out what you weren’t able to grasp the first time around. This is the fourth in a series of posts investigating the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy (you can find the first part

This is the fourth in a series of posts investigating the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy (you can find the first part