The Time is Out of Joint: The Silver Skull, A Review

The Silver Skull is the first book in a new series by Mark Chadbourn, Swords of Albion, following the adventures of Will Swyfte, spy for Queen Elizabeth the First of England, as he fights a secret war against the faerie-folk of the Unseelie Court. That’s a brilliant hook for an ongoing series of adventure novels. And in fact Chadbourn’s new book is best described as modern-day pulp, with all the strengths and weaknesses that implies.

The Silver Skull is the first book in a new series by Mark Chadbourn, Swords of Albion, following the adventures of Will Swyfte, spy for Queen Elizabeth the First of England, as he fights a secret war against the faerie-folk of the Unseelie Court. That’s a brilliant hook for an ongoing series of adventure novels. And in fact Chadbourn’s new book is best described as modern-day pulp, with all the strengths and weaknesses that implies.

It’s a swashbuckling tale of adventure, filled with sword-fights, melodrama, action set-pieces, heroes, and villains. But its characters are flat and uninteresting. And, ultimately, its depiction of its setting is gravely disappointing.

Let’s look first at what the book does well. The plotting is strong and sure, and builds nicely through a series of action sequences. Tension is manipulated skillfully, and the staging of events is imaginative and clearly described. Chadbourn moves his story through a number of interesting places in the Elizabethan world, filling those places with cloak-and-dagger suspense, mysterious riddles, ancient Indiana-Jones-style deathtraps, and the like.

There’s no doubt Chadbourn’s got the basics of the adventure tale down cold. Not only is the pace fast without being wearying or monotonous, but the action sequences are key structurally, advancing the plot while also maintaining a feeling of unpredictability. You’re never quite sure what’s going to happen next, and that’s vital.

The actual writing, though, is at best uninvolving. Again, it’s pulp-like in both good and bad senses. As I said, it’s clear, even when describing complex action scenes, and the descriptions of the various settings are strong. But the flip side of clarity is that sometimes it’s too obvious, telling us things where it would be more effective to show us (“He tried to recall the last time he had felt that warm innocence himself, but it had long since been driven out of him”). I found the rhythm of the sentences monotonous, and more likely to be clunky than deft. The turns of phrase are, if not cliched, at least frequently very familiar.

Worse, the dialogue is unmemorable. There’s an absence of wit in the book; little humour, but also few resonant dramatic lines either. Some of the situations Chadbourn creates cry out for an exchange of biting phrases between adversaries; that never really happens.

But in general, the worst aspect of the book is its depiction of character, or the lack of same. Will’s an uninteresting protagonist; he has no flaws, but also no particularly distinguishing feature. He’s a hero, and that’s that. He has a lost love he pines for … but it never really feels real. There’s a blandness about him that hinders the story.

The minor characters are a mixed bag of stereotypes; again, pulp-like. Will’s servant is Batman’s Alfred, a good friend with a sharp tongue (in theory; in practice his verbal jabs don’t have any spark to them). His henchmen are a drunk, a hard man, and a sadistic psychopathic earl. The female characters fare worse: there’s Will’s pseudo-love-interest, who has an annoying habit of getting captured; a sexy villainess; and a Spanish nun, sister of Will’s archenemy, who’s prepared to tell all to the dashing English spy who stirs her to a moment of passion.

Ultimately, the adventure tale’s undermined by the generic characters who populate it. The action sequences, however fine their choreography, feel almost unpopulated. You’re lacking somebody to cheer for, some reason to feel really involved with the story.

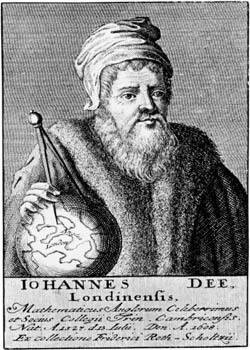

The most interesting characters in the book are, without exception, based on actual historical people. Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster; Doctor Dee, the court magician and astrologer; Francis Drake, the piratical sea-captain; Elizabeth herself, who is unfortunately hardly in the book at all. Amusingly, one of Swyfte’s contacts is Christopher Marlowe, a different Marlowe than the traditional historical figure, “intemperate & of a cruel heart.” Here, he’s weaker, worrying about the morals of spy-craft.

The most interesting characters in the book are, without exception, based on actual historical people. Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster; Doctor Dee, the court magician and astrologer; Francis Drake, the piratical sea-captain; Elizabeth herself, who is unfortunately hardly in the book at all. Amusingly, one of Swyfte’s contacts is Christopher Marlowe, a different Marlowe than the traditional historical figure, “intemperate & of a cruel heart.” Here, he’s weaker, worrying about the morals of spy-craft.

In fact, the characters spend a fair bit of time discussing how grey and dispiriting the espionage world is. It’s oddly out of place; the book seems to aim at being a swashbuckler, but the characters think they’re in a John le Carré novel. It might work if the characters felt more credible, but they have neither the individual depth, nor the sense of being part of a real society, needed to pull that off.

In fact, Chadbourn’s depiction of the Elizabethan age is problematic in general. He doesn’t seem to have grasped the world-view of the era, the mix of Renaissance humanism and Neoplatonic philosophy and pseudohistory that people accepted as the way things were.

At one point, Swyfte tells a confederate that “We are taught to see the world a certain way. A clockwork place, where the sun rises in the morning and sets at dusk, and all happens as it should. Tick-tock.” But this is anachronistic. The image of the world as a clockwork place, as defined by reason, was common in the eighteenth century, not the sixteenth; in fact, the word “clockwork” doesn’t appear in print before 1648. The Elizabethan Age was not an age of reason.

That’s not to say that the Elizabethans didn’t have a complex understanding of the world and the cosmos. But consider C.S. Lewis’ description of the Elizabethan perspective: “tingling with anthropomorphic life, dancing, ceremonial, a festival not a machine.” This is vastly different than the clockwork universe of eighteenth century rationalists.

This was still a time when atheism was blasphemy; when the idea that the earth moved about the sun was new-fangled and suspicious. The scientific method had not yet been invented. Witches and miracles were just part of the way the world worked. And elves, too; Lewis notes that a woman was burned in 1576 for associating with fairies and “the Queen of Elfame”. A look at Keith Thomas’ magisterial Religion and the Decline of Magic makes the point that “It is true that the more sophisticated Elizabethans tended to speak as if fairy-beliefs were a thing of the past … Yet in the late seventeenth century Sir William Temple could assume that fairy beliefs had only declined in the previous thirty years or so.”

This was still a time when atheism was blasphemy; when the idea that the earth moved about the sun was new-fangled and suspicious. The scientific method had not yet been invented. Witches and miracles were just part of the way the world worked. And elves, too; Lewis notes that a woman was burned in 1576 for associating with fairies and “the Queen of Elfame”. A look at Keith Thomas’ magisterial Religion and the Decline of Magic makes the point that “It is true that the more sophisticated Elizabethans tended to speak as if fairy-beliefs were a thing of the past … Yet in the late seventeenth century Sir William Temple could assume that fairy beliefs had only declined in the previous thirty years or so.”

The point is that the Chadbourn’s book takes place in a time before reason had quite taken over, but also at a time where reason was emerging as a major force in human affairs. The fascinating thing about the Elizabethan era generally, I think, is the way it looks both forward to modern rationality and also backward to medieval superstition. There’s a new sense of the significance of the human individual, but that individual’s situated in a firmly theistic cosmos, shaped by astrology and occult philosophy.

There’s no hint of this in the novel. In fact, Chadbourn has one of his (fictional) characters be deeply shaken by encountering evidence of magic. This, despite the fact that one of his (historical) characters, Doctor Dee, was notorious as a wizard. In other words, the attitude Chadbourn wants his character to have is in conflict with a necessary element of his setting, as depicted in the book. (Consider also that the same character claims to know “a little” of the history of England; at the time, that history would have included King Arthur, King Lear, Cymbeline, and, depending where and when he learned his history, possibly even the existence of a race of giants overthrown by descendants of the Trojans.)

Another way to put it is to say that Chadbourn subordinates the actual nature of the era he’s working with to a standard type of contemporary story: the story of a rational world secretly threatened by the forces of wild magic. That’s a story that works if you set it at almost any point in the last three, even three and a half centuries. But it doesn’t work when you try to set it more than four hundred years ago. It feels ultimately like Chadbourn passed up a potentially interesting approach in favor of something more generic, more easily understood by people today.

That business about being “secretly” threatened doesn’t help. Apparently the kings and queens of England tried to keep the existence of the Unseelie Court hidden from their people, because, according to Will, “if the good men and women of England knew the terrors that could pluck them from their lives at any moment, they would be driven mad with fear”. How that worked as dynasties shifted during the Wars of the Roses and after I don’t know. And how it works when the Unseelie Court are strong enough to send representatives wandering into the royal court of Scotland without concern I also don’t understand. But given how widespread fairy beliefs were in England, perhaps the answer is obvious: it didn’t work well at all.

What I mean to say is that the X-Files-esque idea of a government trying to keep the existence of a supernatural world under wraps doesn’t work when everybody already believes in these things, and has for hundreds of years. Again: it’s an idea that crops up in modern fiction, and Chadbourn’s using it here without any evident consideration for whether it makes sense in the Elizabethan Age.

If I seem to be making a big deal of these things, it’s not only because I find these approaches weaken the sense of the book’s setting, but because I think it represents a tremendous lost opportunity for the book’s story. The Elizabethan Age was, as I’ve said, a time in transition, and that’s always interesting. It was an age that wanted to believe in hierarchy, whether in the stars above or in human society on earth, but which saw those hierarchies challenged or falling everywhere—in Copernican astronomy, or in the increasing numbers of “masterless men” roaming the country. Touching on these things could have given Chadbourn’s book even more energy, and also helped situate his tale within a credible world. A historical fiction writer has to build a world just as much as a fantasy writer; and I don’t feel that Chadbourn either grasped the world he had to work with, or constructed a satisfactory alternative.

Of course, the Elizabethan Age was also a time when a new depiction of faeries emerged. From the threatening, powerful fay of folk myth, they turned into the tiny, whimsical things of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Chadbourn doesn’t touch on this changing view of the elf-folk; but then he doesn’t really seem to have much of a sense of exactly what Will Swyfte’s Enemy (the term’s always capitalised in the book) actually is.

That Enemy is called the Unseelie Court; but are they elves or devils? Or both? And what powers do they actually have? Swyfte and the other characters talk about them as a nigh-unstoppable force, only held at bay by the magic powers of Doctor Dee; but in fact when Swyfte fights them, they fight like men and indeed die like men.

Can they work magic? One of the best passages of the book has Will’s not-quite-love-interest getting trapped in an illusion wrought by the Unseelie Court; but when Will himself is captured by the Enemy, they simply torture him, as any earthly power would do. (In fact, they waterboard him. I don’t know what the intent of that passage was, but it seemed spectacularly out of place.) Surely a well-wrought illusion would have worked better than torture; surely, if the Court is so powerful, they have some magic that could overwhelm his mind without resorting to crude physical measures.

But it seems not. In general, the lack of detail given to the Court, the lack of any real sense of what they can and can’t do, seems to me to undercut the credibility of the world, and to make it difficult to feel any sense of danger. You don’t know enough about the Court to be afraid of them. Instead, Swyfte and his men seem to give their Enemy too much credit for magical powers. Without a real demonstration of inhuman magic, it’s difficult to grasp what exactly the big deal is about the Enemy’s power; and when they’re caught flat-footed, as they are during a crucial flashback scene late in the book, it’s hard to take them seriously as more-than-human intelligences.

But it seems not. In general, the lack of detail given to the Court, the lack of any real sense of what they can and can’t do, seems to me to undercut the credibility of the world, and to make it difficult to feel any sense of danger. You don’t know enough about the Court to be afraid of them. Instead, Swyfte and his men seem to give their Enemy too much credit for magical powers. Without a real demonstration of inhuman magic, it’s difficult to grasp what exactly the big deal is about the Enemy’s power; and when they’re caught flat-footed, as they are during a crucial flashback scene late in the book, it’s hard to take them seriously as more-than-human intelligences.

But power aside, there’s no real sense of any special atmosphere to the faeries or faerie lore. Chadbourn says that his fay-folk haunt blasted heaths and moonlit moors and the like, but never quite manages to evoke the real otherworldly air you find in the stories of (say) Katharine Briggs’ Dictionary of Fairies. Again, it feels like Chadbourn doesn’t take full advantage here of the material he’s working with.

So the result, taken all in all, is a competent pulp action tale, but one which lacks the vividness of the best pulp historicals, and the sense they had of grasping what’s really cool about their eras. Chadbourn’s got a great idea, but his lack of a feel for the setting he’s working with hampers it, as does the lack of memorable characterisation, and the lack of any definition for his villain’s abilities. His way with an action scene is quite strong, and the overall plot structure feels solid. The sum total is a decent action-adventure book; decent enough to leave you wishing it had been a bit more.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.